The real moneymakers of March Madness

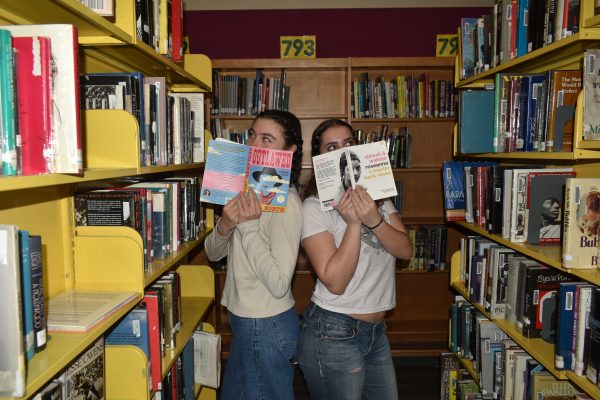

Clarion photo Getty Images

PHILADELPHIA, PA – MARCH 24: Tyler Thornton #3 of the Duke Blue Devils makes a three-pointer at the halftime buzzer against the Creighton Bluejays during the third round of the 2013 NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament at Wells Fargo Center on March 24, 2013 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Photo by Rob Carr/Getty Images)

Some of you may read this article interested in seeing a personal perspective on March Madness; others may be reading to figure out what it exactly is that everyone has been talking about for the last two months. As an explanation for the latter group of people, March Madness is a college basketball tournament that takes place during the month of March on an annual basis. It’s also a platform for creating brackets (deciding who you think is going to win individual games) and betting or gambling. This tradition takes place all around the country, and is especially popular in offices. Although betting on college sports is technically illegal, it isn’t why I object to the entirety of the tradition. The reason I object to the tradition is because the people who win their small office gambling pools are making more than the players that they’re betting on.

According to television news site, TV by the Numbers, March Madness has generated at least $7.5 billion in advertisements alone over the last 10 years. Schools do profit from that (though not all equally), but so do individuals. One coach in the NCAA, Dabo Swinney, makes $3 million every year, meanwhile insisting that the athletes who play in these games continue to not make financial profit. Not only do they not profit, but if players are caught accepting any form of help for any reason, they are no longer allowed to play. This is because it’s breaking the NCAA rules, which state that “receiv[ing] material benefits that are not available to the general student body” is illegal. This includes food, gifts, or anything tangible coming from any person, as a congratulations or otherwise.

Of course, just like with every argument, there are people with opposing opinions to my own–including many coaches and sports newscasters–who often have the same arguments affirming the status quo. The most common defense you’ll see is that student athletes are paid with an education. That makes sense, right? You play a sport, the school pays you to do it by allowing you to learn in their facility. Well, let’s take a look at why this isn’t exactly all it’s cracked up to be.

Though at a glance this statement may be true, many people–including myself up until a few weeks ago–don’t understand what kind of strings are attached to these athletic scholarships. You don’t just have to be injured to lose your scholarship. Actually, it could be just about anything. Talking back to the coach (who makes money off of you playing) who then kicks you off the team? Good luck on your own. Not doing as well as the program thought you would? Have fun paying for college yourself. There is no guarantee that an athlete will get to keep their scholarship. They could lose it at any time for any reason, and there’s nothing they can do about it. The education is only as dependable as the scholarship; that is to say, it’s not at all dependable.

Another argument against paying NCAA athletes is that once you begin to pay for one extracurricular activity, you will have to start paying for all of them. First it’s sports, then it’s band, drama, debate…and who knows where it could go from there! The problem with this argument is a sad but simple truth; non-sport extracurriculars are not as profitable as sports. At least, not as far televised commercialism goes. Whether or not this is how it should be is an entirely separate conflict.

There are many arguments on either side of this debate, and there’s no way to fit them all into a high school newspaper article. However, if you feel inclined to learn more, you can google “Why student athletes,” and the first two suggestions that Google will give you are: “Why student athletes should not be paid,” as well as “Why student athletes should be paid.” And remember that regardless of how you feel about this issue–or any other, for that matter–the best opinions are informed opinions.

Katherine Jones was an active participant in Mr. Sorensen’s third period English class her junior year. With friends in newspaper, she spent a lot of...