Cleveland Needs a Name Change

Clarion photo Sean Lee

Editor’s Note: Trigger warning. This story contains information about sexual assault and may be triggering for individuals.

Cleveland High School has many notable alumni and is considered one of the better schools in Oregon, so I imagined that President Cleveland was chosen as its namesake to reflect that excellence. However, upon doing some research on him, I stumbled across a VICE article called “Grover Cleveland, a Rapist President” by Jamie Lauren Keiles. The title alone completely shocked me, but after I read the article itself, I felt horrified and disgusted. The story sounded like the tawdry plot of a bad soap opera: sexual assault, a child born out of wedlock, abduction, victim-blaming, and cover-up. But this wasn’t some silly TV show but instead the unfortunate and heartbreaking story of Maria Halpin, a woman who never received any justice. After that one article, it seemed now that our high school was named after a man who preyed upon a vulnerable woman and then did everything he could to destroy her life while also climbing up the ladder of power all the way to the presidency. I realized that I had to read more; it didn’t get any better. Although Maria Halpin passed away in 1902, I would like to see her finally get the justice she was never able to receive while alive.

Grover Cleveland was born in 1837. Before becoming president in 1885, he worked in various prominent positions, including ward supervisor, sheriff, assistant district attorney, mayor of Buffalo, New York. His victim, Maria Halpin, was a young widow from Pennsylvania who had to leave her two children behind in Jersey City, NJ, when she moved to Buffalo around 1871. She was 38 years old when she met Grover Cleveland while on her way to a birthday party. Cleveland walked up to her and invited her for dinner. She was hesitant at first because she had plans, but he was persistent so she agreed. After dinner, he walked her to the boarding house she was living in and violently raped her in her room. Maria in complete shock began to cry, to which Cleveland promptly replied, “Why are you blubbering like a baby?”

After the sexual assault, Maria considered going to the police, but Grover Cleveland was a lawyer at the time, had been the sheriff for numerous years prior, and had many law enforcement connections. When she told him she wanted to involve law enforcement, he threatened her. She said he told her that “he was determined to ruin me if it cost him $10,000 if he was hanged by the neck for it.” She told him she never wanted to see him again. Six weeks after the rape, Maria discovered she was pregnant with Cleveland’s baby. She hadn’t been with any other man since the assault and was positive it was his child. Cleveland was well aware of this fact, but he continuously denied that the child was his up until the birth. He wrote a contract with Maria to pay her $500 if she put the baby up for adoption and never spoke to him again. She agreed.

On Sept. 14, 1874, Oscar Folsom Cleveland was born. Grover Cleveland arranged for Maria to give birth at the only hospital for unwed mothers in Buffalo. The doctor was a close friend of Cleveland’s named James E. King. Upon the birth of his son, Cleveland sent a judge and two of his personal detectives to separate Maria from her child. The judge gave the baby to the doctor, and he took the baby to the house of Minnie Kendall, his sister-in-law, who was pregnant and due any day. King and Cleveland wanted Kendall to pretend she had twins and raise both babies as her own.

When Maria returned home after the birth of Oscar, she became very depressed. The doctor hadn’t even told her if the baby had lived, instead, they ripped him from her arms. Maria felt a lot of shame due to how sexual assault victims were treated at this time, but she wanted to raise Oscar as her own. She knew the only way she would be able to raise Oscar and feel less sinful for giving birth to an illegitimate child was if she and Cleveland were married. She went to Cleveland’s office and begged him to marry her and let her see Oscar. Cleveland was infuriated with Maria because this was in direct violation of their original contract, but Maria was persistent. A few weeks later, Cleveland arranged a meeting between Maria and the baby. The doctor’s sister-in-law brought the baby to Cleveland’s office. This should not be mistaken as a kind gesture or an act done out of concern for Oscar or Maria. Cleveland used this as a means of getting her off his back for a brief period of time.

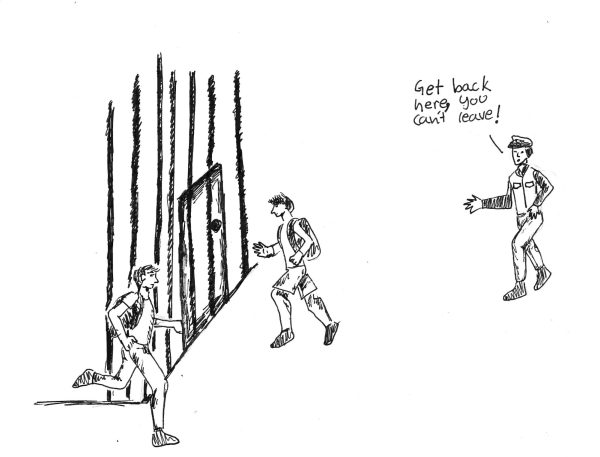

About a month after Maria had seen Oscar, she actually “stole” him and kept him in her care for months. Maria went to Cleveland once again to try to convince him to marry her and raise their baby together, but this angered Cleveland instead, so he sent his friends from the police department to take Oscar and bring Maria to Buffalo’s Providence Lunatic Asylum. Maria was dragged into the building kicking and screaming that she should be released immediately because she was not insane and definitely did not belong in there. This would be the last time Maria saw her baby; Oscar was placed in the Buffalo Orphanage Asylum.

Maria left the hospital absolutely defeated and heartbroken; she’d lost her baby and had just undergone an extremely traumatic and unjustified series of events. After her stay in the lunatic asylum, she made the decision to take legal action against Grover Cleveland and announced her intent to charge him with assault and abduction. Maria went to Milo A. Whitney, a notable Buffalo attorney who was fascinated by Maria’s story. She told Whitney that Cleveland had plotted the abduction and hired the men to carry it out, as he had previously tried less violent means to separate her from her child and get them out of the way. Maria also showed him the contract that swore she would give up Oscar and never speak to Cleveland again. But, unfortunately, Maria’s family pressured her to give up the baby because it stained the Haplin name. Maria never went through with the lawsuit and instead took another settlement from Cleveland, using the money to open a dress business in Niagara Falls, NY.3

Ten years after the sexual assault of Maria Halpin, her rapist’s name – Grover Cleveland – was plastered everywhere. It wasn’t because Maria finally was receiving justice, it was far from it actually. After Cleveland’s years of being a lawyer, he was elected the mayor of Buffalo. Eight months later, he became the governor of New York. Two years after that, he began his run for president. Grover Cleveland ran as a Democrat in 1884 against Republican James G. Blaine from Pennsylvania. The election was full of scandals and theatrical drama that swept over America; the race itself became more like a contest over who could dig the most dirt on the other candidate. Democrats revealed that Republican candidate Blaine had earned substantial sums of money from a backdoor deal with the Union Pacific Railroad and was trading congressional favors for cash. As a rebuttal, the Republicans exposed the story of Maria Halpin, the rape, and the illegitimate child.

A newspaper called the Evening Telegraph got a letter from a local minister, Reverend George Ball, telling them about the scandal.1 The letter portrayed Cleveland as a drunk who had harassed women. It also contained dark descriptions of bar fights and all-night Sunday liquor parties where Cleveland and his friends behaved inappropriately around women. The most striking allegation was that Cleveland had fathered a child out of wedlock with Maria Halpin and used his authority to have her committed to an insane asylum so he could take the child out of her custody. Americans everywhere were shocked by this news, which gave rise to the chant: “MA, MA, WHERE’S MY PA?”.8

Cleveland knew he needed to rebut the allegation that could potentially cost him the election. He quickly put out a statement full of falsehoods that completely defamed Maria. Cleveland claimed that she’d slept with all of his friends, several of whom were not only men of power and importance but were also married at the time, and that he, Cleveland, the only bachelor among them, agreed to take responsibility for the child, despite his doubts about paternity. In the media, this act was portrayed as brave and his story was never questioned by supporters. And so, in November 1884, Maria Halpin’s rapist was elected as the 22nd president of the United States. It seemed, at that time, that American voters were more concerned about how someone treated money than how someone treated women. In the 21st Century, we can do better.

With half the students at Cleveland High School identifying as female, I think we should reconsider the name. The “Me Too” social movement has shined a light on a dark part of this country’s recent history. Many powerful men have finally faced consequences for their appalling treatment of girls and women, some losing their jobs and even their freedom. Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby come to mind. Can you imagine if our school had been named after one of them? The fact that nearly 150 years ago, Maria, a single mother with no money or power, tried to fight back seems way ahead of her time and very brave. Shockingly, before 1919, she couldn’t have even voted against him! In my mind, she’s the true heroine here and deserves her due. He, on the other hand, should be remembered, but his sins must not be forgotten. Although no one is perfect, I can imagine our school could find a much more worthy human being for its name.

Bibliography

Collaborative, Rise. “Why Maria Halpin Didn’t Report.” Rise Collaborative, 19 Mar. 2019, risecollaborative.com/rise/maria-halpin-grover-cleveland.

Graff, Henry. “Grover Cleveland: Life Before the Presidency.” Miller Center, 4 Oct. 2016, millercenter.org/president/cleveland/life-before-the-presidency.

Lachman, Charles. A Secret Life: The Lies and Scandals of President Grover Cleveland. 1st ed., Skyhorse, 2013.

“Grover Cleveland’s Sex Scandal: The Most Despicable in American Political History.” The Daily Beast, 13 July 2017,

www.thedailybeast.com/grover-clevelands-sex-scandal-the-most-despicable-in-american-political-history.

“Maria Halpin.” Buffalo Stories Archives & Blog, Buffalo Stories, blog.buffalostories.com/tag/maria-halpin.

Morris, Tim. “Lection: A Secret Life.” Lection, 25 July 2012, tmorris.utasites.cloud/lection/120525.html.

“San Francisco Call 8 February 1902 — California Digital Newspaper Collection.” California Digital Newspaper, cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SFC19020208.2.11&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN——–1. Accessed 29 May 2021.

Serratore, Angela. “President Cleveland’s Problem Child.” Smithsonian Magazine, 26 Sept. 2013, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/president-clevelands-problem-child-100800.

Wikipedia contributors. “Grover Cleveland.” Wikipedia, 23 May 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grover_Cleveland.

. “James G. Blaine.” Wikipedia, 27 May 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_G._Blaine.

www.bibliopolis.com. “‘Tell the Truth!’ ‘Here It Is!!’ Maria B. Halpin’s Statement!!! By Maria Halpin On.” James E. Arsenault & Company, James E. Arsenault, www.jamesarsenault.com/pages/books/5266/maria-halpin/tell-the-truth-here-it-is-maria-b-halpin-s-statement?soldItem=true. Accessed 29 May 2021.