In November of 2020, Oregon voters passed Measure 110, the ambitious Drug Addiction Treatment and Recovery Act. The legislation went into effect on Feb. 1, 2021, and aimed to decriminalize personal drug use widespread throughout the state and establish more services to help drug addiction.

Now, more than two years after the implementation of Measure 110, voters feel they have been misled. They expected that people suffering from addiction would–instead of getting put in jail cells and spiraling further–be given access to proper medical and rehabilitation services. However, many Oregonians believe that decriminalization has contributed to the rising crime rates and overdoses. With law enforcement no longer able to coerce drug addicts into treatment or rehabilitation, those suffering from addiction simply aren’t getting the help they were promised.

Measure 110s shortcomings have been painfully obvious. Firefighters from Station 1 in Portland responded to 300 overdoses, in June alone. Additionally, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), annual opioid overdoses rose by 61 percent in 2020 from around 471 to 1000 deaths. The transient population also increased by more than 50 percent from around 11,000 in 2020 to more than 18,000 in 2023 (OregonLive). Although these statistics cannot be solely blamed on Measure 110, they show that it certainly failed to help communities with many vulnerable or minority groups, which is incongruous with what the initial campaign suggested.

Jennifer Pool, a former resident of Portland who used to be a tutor for Cleveland students, believes that the passing of Measure 110 contributed to a decline in her neighborhood. “I first moved to SE Portland in 2000 and felt safe living in and walking around my neighborhood. On the rare occasion there was an issue with crime, I could always get through to the non-emergency line, and a police officer would arrive in a timely manner. However, after Measure 110 passed, I witnessed more use of drugs, like homeless people shooting up heroin in front of our house during the day, and our neighborhood felt lawless at times. We had more and more instances of crime in and around our property, and I could no longer get through to the non-emergency line when I needed help,” Pool said.

She communicated how she and her family increasingly felt more scared living in their neighborhood and even in their own house. As a result, her family decided to move outside of Portland to a safer area.

Pool remains upset that she had to move from an area she had previously loved and is frustrated that she voted for Measure 110. “I thought Measure 110 would offer beneficial services to people with addictions and reduce prison time. Instead, the drug addiction problem increased throughout Portland and, in my opinion, has contributed to the increase in crime,” she said.

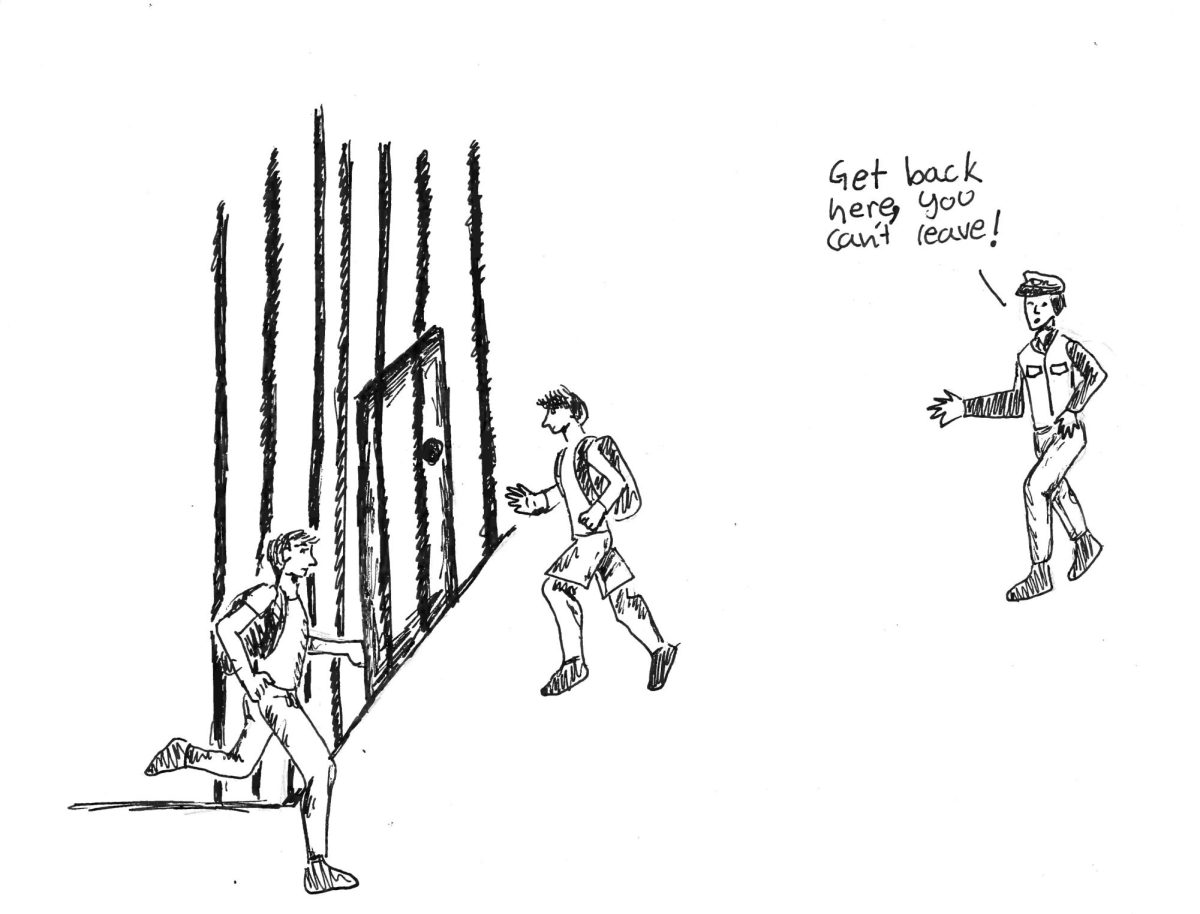

Many Portland police also share her sentiment. Before Measure 110 passed, law enforcement had the power to mandate people with serious addictions into treatment, for example residential counseling. However, small amounts of extremely dangerous drugs like heroin (one gram or less), cocaine (two grams or less), and methamphetamine (two grams or less), that could previously warrant an arrest, now only warrant a citation. Police officers feel powerless to do anything about the now much more numerous amount of substance abusers endangering the community.

Christopher Campbell, a PSU professor, explained In a KGW interview that decriminalization has been hard to navigate for police officers in Portland: “One of the things we found is that officers are skeptical of how decriminalization can motivate people to voluntarily seek treatment, which is manifested into officers being far less willing to hand out citations. For instance, one officer we spoke to from an urban sheriff’s office suggested that they believe Measure 110 took away their ability to recognize their rock bottom, so to speak, and kickstart a new life void of drug use. So this, along with many other reasons, leave officers feeling like giving out citations isn’t really worth their time.”

This attitude is widespread among Oregon law enforcement officers, as Christopher continued to explain: “This issue was really mentioned by about every interview — about 96 percent of every interview — and it really bears out in the data when we look at arrests and citations.”

With opinions deteriorating, many Oregonians now think that the removal or modification of measure 110 would restore order to the urban regions of the state. The Economist reported that by 2022, two years after the start of Measure 110, only 40 individuals called the treatment hotline. The $265 million dollars spent have not shown promising results.

With the people growing discontent and calling into question the effectiveness of Measure 110, it is unclear how much longer it will stay intact. In fact, on Sept. 8, 2023, the city of Medford called for Measure 110 to be modified or repealed, while back in August, the Jackson County commissioners unanimously decided to call for the removal of the measure.

As the drug crisis in Oregon continues to get worse and open-air substance abuse is at an all-time high, it is time for some amendments for the well-identified but mishandled measure. The criminalization of extremely dangerous substances such as fentanyl and methamphetamine will have a large effect on the declining state of Oregon and as we try to rid Measure 110 of the harm it’s caused.

David • Dec 8, 2023 at 1:33 PM

Was a really STUPID idea to begin with! Just generated $265 million wasted tax dollars that could have been put to better use!

David • Dec 8, 2023 at 1:33 PM

Was a really STUPID idea to begin with! Just generated $265 million wasted tax dollars that could have been put to better use!