AI in classrooms has been in the academic spotlight lately due to the discussion around its use in generating essays. Its supporters claim that, due to the rapid advancements made in recent years, the technology will soon be as central to writing as a calculator is to math. However, others say it leads down a slippery slope of academic dishonesty that creates disadvantages for students who provide original opinions in their work. However, regardless of the moral resolution of this debate, the landscape of academic integrity has changed permanently.

The ACT, a nonprofit college readiness organization, has reported in its studies that around 20 percent of high school upperclassmen have used AI tools for school-related activities. Nearly 90 percent of students surveyed in this study said that they won’t use AI for major assignments like college admission essays, due to either the currently primitive state of the language model or ethical considerations.

According to an anonymous Clarion survey, around 40 percent of Cleveland students have used AI in some way academically. Despite this, most students, including those who have used AI, believe that it is an unethical act of academic dishonesty. Students surveyed have a wide range of opinions on the future of AI. The majority of students have concerns regarding the increasingly unignorable capabilities of AI, but around a quarter also believe any improvements to the technology will be, in practice, strictly positive.

The regulation of AI remains a difficult topic for students and teachers to solve. Multiple students suggested giving more class time to reduce the likelihood of students feeling the need to use AI to catch up, a practice that appeared common in comments in the survey. Even many students who were generally against the use of AI in schools admitted to considering using it in certain situations, especially when under pressure.

One student wrote that they considered using it “when an assignment is hard.” Other students said that they would use it to generate ideas.

Even so, many students are against any sort of AI use. Another student commented, “I don’t [use AI] because I take pride in my accomplishments.”

The majority of students agreed that using AI counted as plagiarism. One student wrote that when using AI, “you’re not forming your own ideas. You have to be able to form your ideas in a professional/educational setting, and if you can’t, you have to reference people who have. AI art steals, and AI writing is not your own.”

Another student agreed, saying, “It should (count as plagiarism). It pulls from things published by people online when it isn’t just creatively filling gaps, so it’s passing other people’s work off as your own, which is plagiarism.”

More than 80 percent of students said that someone they know or a classmate of theirs has received an A on an assignment created with ChatGPT.

The average weighted GPA of the participants in the Clarion survey was 3.86, and most were juniors. The ACT study showed that students who had higher ACT composite scores were more likely to have used ChatGPT, which suggests that those who don’t use AI may fall behind.

According to Sadie Adams, an IB History of the Americas teacher and Constitution Team coach, the prevalence of AI has gone down after an initial spike last year.

Regarding student AI use and academic dishonesty, “Between April and May [last year], I had nine parent conferences,” she said. It is understood there has been significantly less demand for such measures this year. She attributes this in part to tools such as Turnitin, which automatically checks student work for AI-generated text and plagiarism.

In the meantime, Adams asserted that vigilant teachers can usually tell whether or not a student “sounds” like themself in submitted work.

“It is easy for me to detect it because I pay attention to how they write. I found the texts to be pretty glaringly apparent. It’s because it’s not their voice. Right now, at least, AI has a very different voice,” Adams said.

Despite the constant improvements in artificial intelligence, Adams remains confident that Turnitin will continue to remain effective in the future. She maintained, “To meet the demands in college and in high school, the technology around detection is growing nearly at the same rate as the AI.”

In the Clarion survey conducted, only 20 percent of respondents said that teachers “thoroughly” understand the prevalence of AI in their classes, 46.7 percent said teachers “somewhat understand,” and 26.7 percent said teachers “do not fully grasp” the extent to which AI is used.

One student explained that AI seems most used in humanities topics. “I’m aware that a lot of people use it to do written assignments for classes such as HOTA with a lot of written work. In Sophomore Inquiry last year most people used it to get over 10 days of writing in less than an hour when changing up their wording. The sad thing is that most of the detection softwares teachers claim to run work in are rarely or never used in reality. Most AI checkers also can not distinguish ChatGPT work with changed wording or premium AI software writing that is undetectable and more advanced.”

Mary Rodeback, a senior IB Language and Literature teacher, is conflicted about the rightful place of AI in the classroom. “You know, when I initially heard about the inception of generative AI, my hair was on fire because I thought, ‘what an atrocity!’ and then after reading quite a bit about it, and playing around with it a little bit, I started to realize that it’s a tool in the world and it’s not going to go away,” she said.

Rodeback said that some Language and Literature teachers built AI into an in-class exercise. “The senior teachers from lang and lit this year had kids play with generative AI when we were working on personal narratives this year. The results were pretty fascinating. We had kids write six-word memoirs, which are challenging, and then we had to ask AI to transform that six-word memoir into a personal narrative. […] Some kids got stories that work close to it. Yeah, shockingly close, uncanny,” Rodeback said. “Most kids had to go back in maybe six or seven or eight times to arrive at something that sort of closely approximated.”

In terms of AI use and social significance, Rodeback said, “If you’re using it to do your homework, that’s lame and lazy. The work that you’re presented in class, I would argue, is for you to learn. When I assign work, it’s because I’m interested in the students’ actual growth. I don’t think you’re going to grow if you don’t try do the work yourself.”

Rodeback continued, “One of my friends, when I was in graduate school 10,000 years ago,said, ‘Writing is thinking on paper.’ To the extent that we’re able to write well, we’re demonstrating our ability to sort through our thinking and organize our thoughts in a way that makes those thoughts coherent and interpretable/discernible to a person outside our organism. […] If we’re to treat AI in the realm of writing, like a calculator, I think we’re basically suggesting that thinking is no longer a worthwhile endeavor or to refine. That’s, frankly, terrifying to me.”

Adams voiced similar concerns saying, “I think one of the most important skills that students need to develop in high school to be ready for the real world is critical thinking.”

To reduce AI use, a respondent in the Clarion survey said, “I think that teachers should put in more effort for using AI detection software and use them for more assignments. I do not know how good it is, but I believe that there is a Canvas integration that can check for AI through Google Assignments. Teachers should also have training to allow them to detect when work is AI-generated, because it is pretty obvious to tell if it is if you know how.”

In terms of prevention, teachers could start “prioritizing work done in class/giving enough time for students to do work in class [and] educating students why exactly AI shouldn’t be tolerated,” a respondent said.

The International Baccalaureate organization released a statement in 2023 on the use of AI. A section of the statement read: “The IB believes that artificial intelligence (AI) technology will become part of our everyday lives—like spell checkers, translation software and calculators. We, therefore, need to adapt and transform our educational programmes and assessment practices so that students can use these new AI tools ethically and effectively. The IB is not going to ban the use of such software, but will work with schools to help them support their students on how to use these tools ethically in line with our principles of academic integrity.”

This is the only occurrence where teachers may be grateful for Cleveland’s wifi issues as it prevents access to other resources for academic dishonesty.

The Era of “Cheat”GPT: Prevalence of Generative AI at Cleveland

February 13, 2024

Categories:

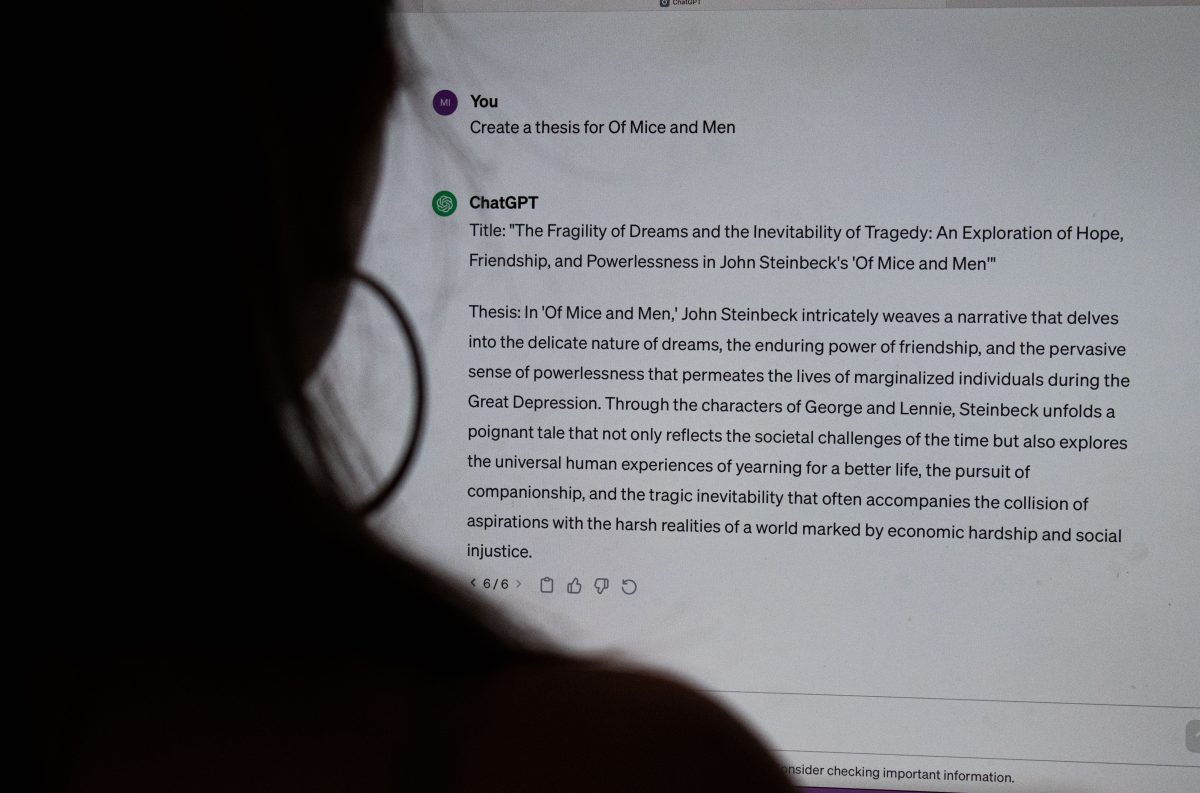

Clarion photo Minying Zhen

Student uses ChatGPT to generate a thesis for ‘Of Mice and Men’, a novel typically read in sophomore English.

0

More to Discover

About the Contributors

Jacky He, News Reporter

Hello! My name is Jacky He, this is my first year on the Clarion. I am currently a Sophomore at Cleveland, I plan to cover big picture news around Portland!

Lily Lockwood-Keil, Online Co-Editor in Chief

Hi! This is my third year writing for The Clarion, I most enjoy reporting on administrative changes, writing opinion pieces about different cultural observations, and occasionally work on graphics. In my free time, I love to journal, kickbox, and stay involved with political causes I care about.

Finn Brewer, News Reporter

I’m Finn, and I’m currently a Junior at Cleveland. I run for Cleveland’s cross country team, and I enjoy hiking and backpacking in my free time.

Minying Zhen, Photography Editor

My name is Min, and I’m a Junior at Cleveland. This is my second year on the Clarion, and I’m the Clarion photography editor. Woohoo!