In the past few weeks, between harsh final grades from female teachers and sports-related social media posts, it has become clear that many students believe women do not innately deserve respect at Cleveland.

Gender bias is surprisingly tenacious; a clear example is the recent discussion about attendance at sports games. In an Instagram post on Feb. 1, the Cleveland varsity girls’ basketball team displayed a stark comparison between their student section and the section during the boys’ basketball team’s game. The comments were restricted due to ongoing attacks from various burner accounts. We should be celebrating Cleveland’s varsity girls basketball team–if only because of rank–disappointingly, many of the comments showed complete ignorance of their accomplishments. Strictly in terms of rank, the girls basketball team is likely to be more entertaining–though the male team certainly is also worthy of pride. Read more about this incident on The Clarion website.

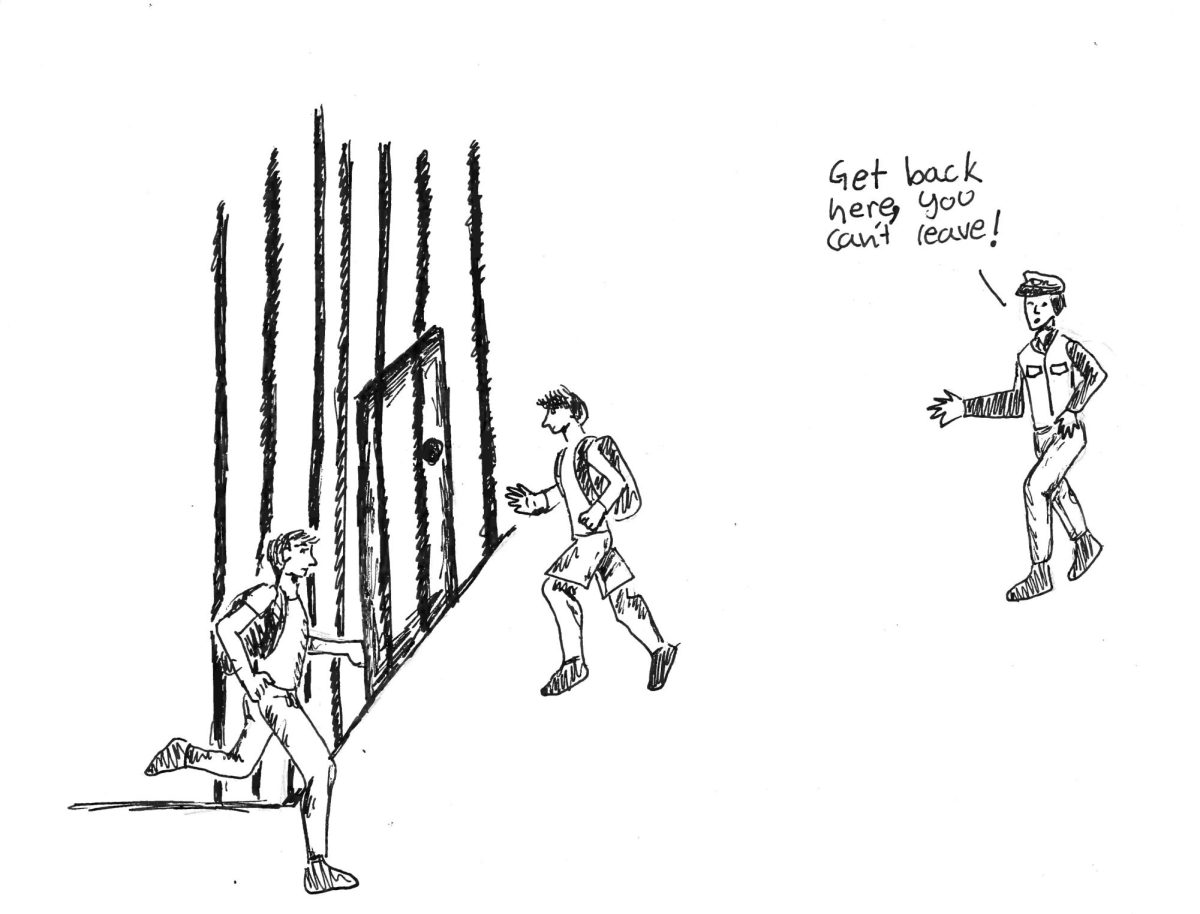

Something more insidious, that takes deliberate attention to notice, is the persistent silencing of girls in class. Male students often directly appropriate comments that women students initially voice, which goes unchecked by many teachers. Personally, in every co-ed environment I’ve been in, this has been a trend. A given feminine-presenting student makes a precise and intelligent comment, only to have it regurgitated shortly after by a masculine-presenting student–who is often validated by a teacher or referenced by a peer. It is not the most studious male students that fall into this pattern of behavior, but typically those who seem to be struggling. In contrast, it would be a perfectly healthy and validating thing for a male student to follow a feminine-presenting student’s comments by explicitly giving her credit and then building on the contribution.

Deepa Narayan’s “Seven Beliefs That Can Silence Women — and How to Unlearn Them” was published in November of 2019. Her TED talk discusses the cultural silencing of women and girls from childhood. She argues that silencing girls prepares them for abuse, and voices that teaching girls to adjust relentlessly teaches girls “not to exist, not to be seen, not to have a self; and it trains boys to claim power and authority.” She wanted to understand the roots of abuse, and, through a thorough interview process, distilled seven principles that erase women:

1. To reject their own bodies, which promotes sexual abuse

2. To be quiet, not to argue, to make space for others

3. To please others at the expense of oneself

4. To reject their sexuality

5. To distrust other women, which prevents them from unity

6. To fulfill their duty rather than their aspirations

7. To be dependent on men

To solve this, as a society, Narayan states, “We don’t need elastic women, we need elastic definitions.” Warped gender expectations have surfaced around teachers just as powerfully. There is a distinct difference in the reputation of teachers with similar rules and expectations that may be largely attributed to gender. This surfaces in discussions about tardiness, late work reception, retake availability, or phone use during class. Where male teachers simply “have strict policies,” teachers that are women are perceived as “annoying,” or, “bitchy.” I’m sure I would be, and have been, unusually aggressive when surrounded by a room of disrespectful students who expected gratuitous nurturing simply because they were taught to expect it from women. Nonetheless, this issue is not only affecting students.

Women learn to self-monitor and are often hyper-fixated on their behavior because there are such firm standards for them. Self-silencing can take place in verbal disclaimers before voicing any opinion, by prefacing a contribution with, “I just thought,” “I’m not sure if this is wrong, but,” or, “Sorry, I wanted to say,…” They learn to attack themselves on impulse. Narayan continued to explain that culturally, expecting women to restrain anger wears down the will to be heard at all.

Most higher-level academia is adversarially-modeled. People are rewarded for disagreeing and challenging previously established truths. One will not succeed in many career fields simply because they are not argumentative, which puts culturally obedient women at a distinct disadvantage. According to Allyson Jule, a Canadian professor at Trinity Western University, boys speak nine times more than girls in elementary classrooms, which teaches girls to make room for boys, and teaches boys to expect attention and take the involuntarily given space.

As a woman at Cleveland, it can often feel like I have to choose between likeability and self-advocacy; I don’t observe male peers having to choose. As many recognize: sex and gender are separate, and science only supports chromosomes, hormones, and reproductive organs—meaning that roles, attributes, responsibilities, and entitlements are not scientifically valid. I am comfortable with my birth gender, and I think of myself as feminine, but I don’t think that there should be such powerful connotations attached to that. This problem of cultural and self-silencing is also made significantly worse for students of color.

I think we need to broaden our definitions of gender more consciously; and I believe that if men were willing to listen and non-men felt safe to advocate their opinions, we would be better-equipped to solve systemic oppression for every minority. To progress, everyone must embrace that discomfort from both viewpoints is essential to stop silencing. I ask that all members of the community, regardless of identity, put more focus on their implicit expectations and the variations of those across gender divides in the classroom.

Works Cited

“Cleveland Boys Basketball Program.” OSAA.org, 9 November 2017, https://www.osaa.org/demo/teams/53155?year=2023. Accessed 5 February 2024.

“Cleveland Girls Basketball Program.” OSAA.org, https://www.osaa.org/demo/teams/53159?year=2023. Accessed 5 February 2024.

Gender, Participation, and Silence in the Language Classroom: Sh-Shushing the Girls. (Jule, Allyson, 2004)

“Gender, Self-silencing, and Identity among School and out of School Emerging Adults*.” ERIC, 2023, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1382232.pdf. Accessed 5 February 2024.

Heikkilä, Mia, et al. “Nine Contradictory Observations About Girls’ and Boys’ Upbringing and Education – The Strength-Based Approach as the Way to Eliminate the Gender Gap.” Frontiers, 6 July 2020, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.00134/full#B112. Accessed 5 February 2024.

Jule, Allyson. “(DOC) ESL Girls’ Silence in Classrooms | Allyson Jule.” Academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/3419728/ESL_Girls_Silence_in_Classrooms. Accessed 5 February 2024.

Maji, Sucharita, and Shikha Dixit. “Self-silencing and women’s health: A review.” PubMed, 5 December 2018, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30518269/. Accessed 5 February 2024.

Narayan, Deepa. “Deepa Narayan: 7 beliefs that can silence women — and how to unlearn them.” TED, 25 November 2019, https://www.ted.com/talks/deepa_narayan_7_beliefs_that_can_silence_women_and_how_to_unlearn_them?language=en. Accessed 5 February 2024.