Generally, youth in America vote less than other age ranges. In the 2020 election, 50% of people 18-29 voted—an 11-point increase from the 2016 election cycle—distinctly less than the 66% national voter turnout, according to Tufts University Tisch College’s Circle and Pew Research Center. Political discussion is notoriously resented in settings of American togetherness, though political dialogue is becoming more acceptable in younger spaces. Attaching this trend to other methods of positive association with civic engagement, I believe that intenti/onally creating positive associations for children of all ages with democracy and participation in politics will lead to a political landscape better-representative of the American people long-term.

K-12 education is one of the best opportunities to improve this representation, as half of the young people who did not vote in 2020 never attended college. Additionally, changes in public education would provide students from marginalized communities greater access to information about the elections. This information could prove crucial, as over 40% of youth who did not vote in 2020 felt unqualified to take part in the political process, according to Circle. On the other hand, only around 10% of young voters felt this way.

Youth engagement with politics has been encouraged more by popular culture in recent years, especially through social media. As youth begin to be exposed more frequently to issues of global importance, the culture has adjusted to provide youth-specific opportunities for engagement: school strikes, social justice trainings, mentorship programs, and non-profit positions/internships.

Jessica Sawyer, the Leadership teacher who also teaches English, is optimistic.“I feel like my freshmen talk about politics a lot, actually, even today. I see a lot of students who are engaged in my leadership classes talking about politics on a national level or even on a city-wide level. I think that they’re interested in it, especially because they’re on the precipice of becoming voters, ” Sawyer said.

That said, there are many easy improvements to be made.

This process must begin in elementary and middle school at the most fundamental level, to be built on in high schools and beyond. Currently, children are often given opportunities to vote on small decisions, for example, to have a pizza party or an ice cream party to celebrate attendance, and provided brief context about governmental structure, but this is minimally built upon until the provided semester of high school government.

Oregon in particular has recently taken steps to inform students about politics by introducing a state-wide requirement for one semester of civics. Although PPS already has this requirement, this will benefit many other students throughout the state.

While the required semester is a good start, government teacher Sadie Adams worries that the single semester will not provide enough time to cover all the necessary material.

“I think a year would have been better,” admitted Adams. However, “It’s so far more valuable than having absolutely nothing at all.” The semester, taught at the sophomore level, also provides a valuable base that is built upon in future classes such as HOTA.

School districts can bridge the content gap until that semester by providing support for extracurricular activities fostered by school districts, incorporating political discussion into a variety of courses, and rewarding generally diplomatic behavior. Raising a generation of people who feel respected and empowered to enact fair change would improve the lives of everyone.

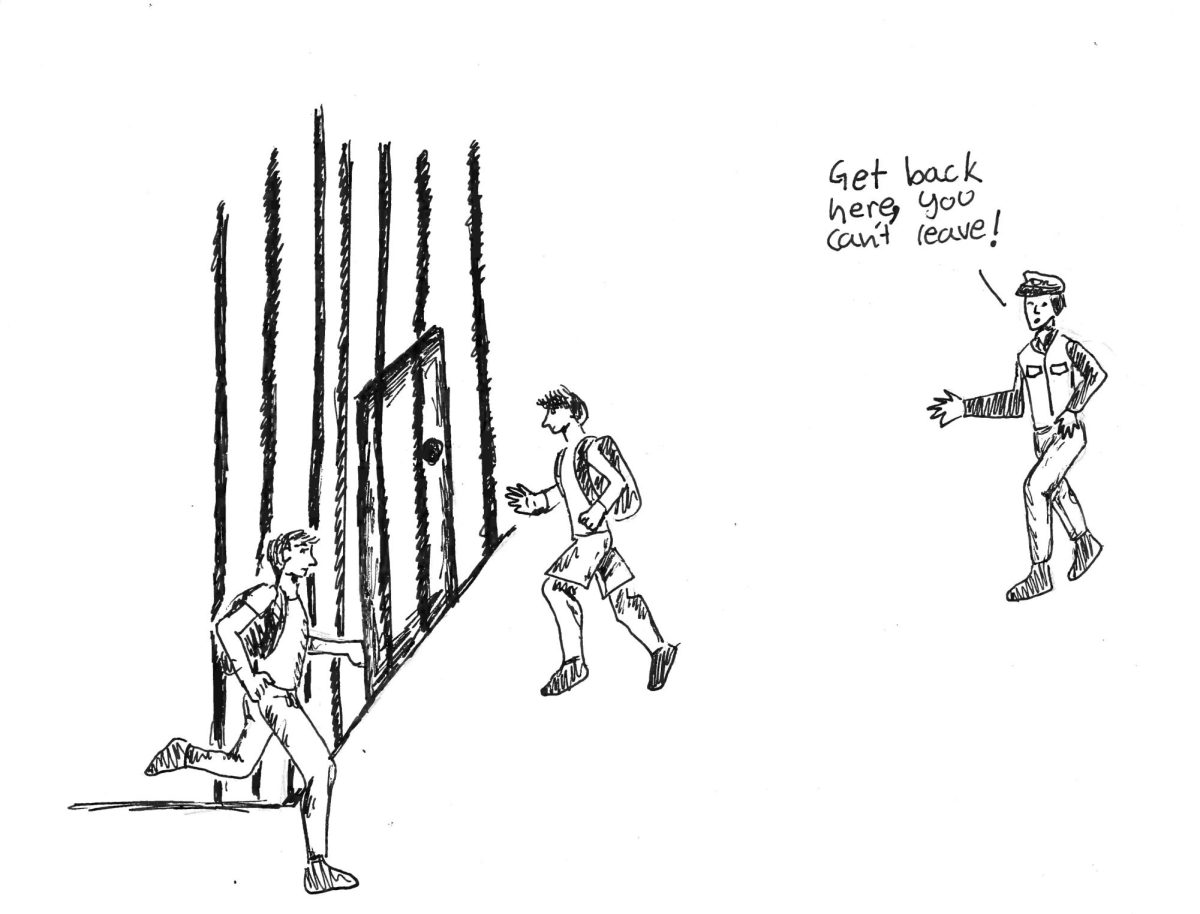

In the meantime, many at Cleveland are openly frustrated with the lack of genuine power and authority given to elected student-body positions. Even placing mirrors in boys’ bathrooms was not possible for a long time, as was frequently discussed in last year’s election cycle.

“I think that initially [positive association with democracy] is why things like student assembled student bodies were created, but the limited amount of power that students are given is kind of like ‘ok, we go through this process, we go through the steps, but then there isn’t any actual power,’” Sawyer said.

This negative association with democratic processes discourages engagement and reinforces the idea that voting is pointless and students’ voices do not matter. Some students have felt pressured out of the race after running for office, but this likely occurs on a subliminal level as well. If no change will occur regardless of one’s vote: why vote at all? This resigned attitude, if carried into adulthood, is perhaps the only evil that all U.S. political parties can unite against.

Many members of the community may be surprised to learn that Cleveland has a constitution that outlines the structure of student government roles. Despite stating, “This constitution will be posted on the school’s website and made available to students by the administration,” it is not on the student website, nor is it possessed by several members of the Cleveland administration.

The simple change of making the constitution more accessible to students would help student engagement by introducing students to their rights in the Cleveland political system.

“You need to understand your role in the political process and what your voice means out there,” said Adams. This process begins with understanding your role in the school’s politics.

Additionally, Sawyer voiced that students ought to be involved in the hiring process. “One of the ways we can increase [passionate engagement in civic structure] is by making sure that students are able to have a say in the hiring process with staff. Like, ‘You’re an elected representative for the senior class and we’re hiring a new teacher, so can you be part of that process?’ I think if students were involved in that, then that could really motivate them to be lifelong participants in the democratic process,” Sawyer said.

Everything aforementioned can be distilled by the simple fact that people need to see that their voices matter. I firmly believe that everyone comes into the world with a will to have their needs met, and it is the culture’s responsibility to nurture its participants and confirm that they will be respected, heard, and rewarded for self-advocacy.

Adams and Sawyer agree that education, as the only insurable factor in the typical American citizen’s life, must promote this ideal by cementing the individual link to state-wide or nation-wide policies. “When you get to the ‘why it’s important to me personally,’ then you can get to the engagement,” explained Adams.

Sawyer explained that on a school-wide level, “I feel like [we need to have] some more practical-application-to-life stuff—where people start asking questions about their life and their bank accounts, then [teachers should] start being like, ‘Oh, well, interest rates are going up, like how does that connect to politics?’ If we’re teaching those things, then we’re leaning towards making politics and government relevant every day for students.”

Youth voters could create a huge difference in topics that America has struggled with for decades. Despite young people feeling the effects of gun control laws and climate change more strongly than older generations, these problems will be hard to fix with the comparably small voter turnout.

Just as voter participation is important, so too is informing the broader population—even those too young to vote—so that people may make confident political choices. Engagement in government is valuable to many, but many people simply see it as a negative aspect of their life–especially in the US–because, regardless of political affiliation, it can often feel threatening and hopeless. To make any lasting change, a cultural reset to make discussion of politics, and democratic/diplomatic processes positive and readily-used is vital.

Works Cited

“Half of Youth Voted in 2020, An 11-Point Increase from 2016.” Circle at Tufts, 29 April 2021, https://circle.tufts.edu/latest-research/half-youth-voted-2020-11-point-increase-2016. Accessed 6 March 2024.

“Oregon Department of Education : Social Sciences : Social Sciences : State of Oregon.” Oregon.gov, https://www.oregon.gov/ode/educator-resources/standards/socialsciences/pages/default.aspx. Accessed 6 March 2024.

“Voter turnout in US elections, 2018-2022.” Pew Research Center, 12 July 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/07/12/voter-turnout-2018-2022/. Accessed 6 March 2024.