To kick off the start of a new school year, Cleveland has implemented the use of Yondr pouches, magnetic-locking pouches that keep student phones and all wireless devices locked away until the end of the school day. Cleveland is one of two high schools in Portland Public Schools that have administered the use of these pouches, along with Ulysses S. Grant High School (which has also banned personal laptops). Although it has been strictly put into action, students have mostly rejected the new policy.

Some students say that not everyone used the Yondr pouches in school—most people still find a way to have their phones out. This may be how the 14 magnets acquired by the school do adequately account for 1400 students.

Despite this disconnect between policy and culture, students largely agree that the pouches have been effective. Owen Woods-Richardson, senior, said, “As an idea, it’s been pretty effective in mitigating phone use. But the people I’ve talked to don’t use the actual Yondr pouches. I don’t think it’s the worst thing, but they could’ve come up with a better solution.”

Similarly, Julian Molinsky, a senior, said, “I think the Yondr pouches themselves don’t do much. It’s more the new policy of, if you have your phone out, you get it taken or you are suspended.” He adds, “They could’ve implemented the same intentions without the pouches.”

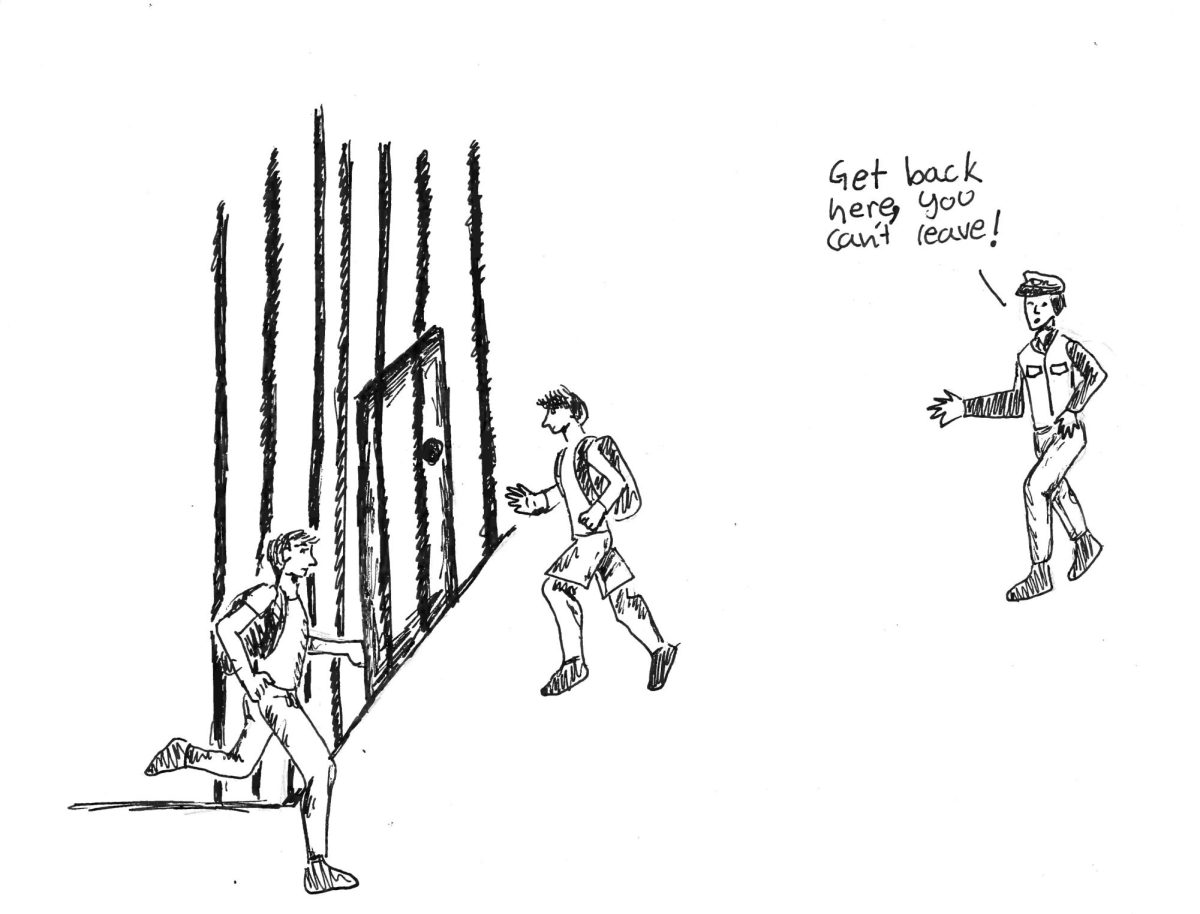

A culture of lingering disobedience with the Yondr policy has been largely attributed to safety concerns. Cleveland students have been known to rely on off-campus restaurants, stores, and places to gather during lunch. In any part of Portland, but especially along Powell, it is unsafe to expect high school students to assume strangers will not pose a threat to their basic safety, or that they may even provide support during potential emergency response. Students must have access to their devices in case of an emergency while off-campus.

In debriefing discussions, students have asked the common question, “Why are we spending $40,000 on this instead of more urgent funding needs?” School counselors are overwhelmed with roughly 300 students each, entire programs have been cut due to budgeting issues, and school staff have been eliminated because of enrollment difficulties (leading to disproportionate class sizes). In addition, many sports teams require better facilities and equipment. Elective tracks have fewer and fewer resources. The culinary class, for example, only has one sink.

The College and Career Center has been directly challenged by Yondr policies, as they have depended on QR codes for many necessary school-wide forms. Additionally, students who rely on digital calendars or commitment reminders cannot access them throughout the entire school day, which limits their ability to attend college visits, meetings with CCC staff, and additional commitments.

These issues are larger components of positive educational outcomes than phone use. “There’s a lot of places the money could go where it’s not going,” Molinsky said. Instead of basic safety precautions, phone use is the top priority.

Principal Wadkins said, “I continue to hear concerns about the phones being locked up at lunch and the need for emergency communication if the student is off campus. The phones can be used to make phone calls by using the voice activation feature on the smartphone. This feature works even if the phone is locked.”

Aside from the fact that many phones do not have that feature, it’s dangerous to speak during most emergency drills. In a scenario such as the increasing concern of a school shooting, being able to get in contact with your loved ones is highly important, and it is not realistic to use a voice activation feature to do that. In a life-or-death situation, we’d prefer to leave last words in a notes app and private messages rather than fighting to be heard in a room full of other students attempting the same thing.

Learning how to obey an externalized phone policy is not a useful skill in comparison to the development of strong internal policies/principles. Technology must be used responsibly, and students deserve an opportunity to try and self-police before attending college and paid jobs. While it is true that devices can be a distraction in the classroom, we have concluded that there are other methods besides a phone-locking pouch that schools could use to decrease phone usage in the classroom. Last year, the use of calculator caddies proved to be successful when actually used, and many students feel that enforcing the caddies would be a better way to limit phone use.

We thoroughly recognize that it should not be a teacher’s job to hound students about improper behavior during class, but also that poor grades should be punishment enough. Just as it is a student’s responsibility to pay attention, it is a teacher’s responsibility to ensure they are gaining something from that dedicated time. If a student is using their phone near-religiously during class and still finishing with an “A,” that class is not at the appropriate level of rigor.

As students who have had extensive, first-hand experience with the Yondr policy, we see value in it when there is a lively community worth paying attention to. Cleveland, as a large school without strong, community-wide principles, is not in a position to isolate students with their peers. In addition, if students are engaged enough in their class activities, they will not feel the need to turn to their phones for entertainment quite as much.

While it is an unpopular policy and Yondr does not appear to have a positive impact, we believe that phone use ought to be monitored and taken into consideration. When examining the various impediments that Yondr poses to personal and professional development, it’s clear that this policy discourages students from involving themselves outside of academics. Phone use has certainly impeded the learning process for many students, but it is much more alarming when one realizes that chronic technology dependence is a symptom of larger fundamental issues in our school.

Whether Yondr was implemented without student input to ease pressure on teachers, or if it was a misguided attempt to pacify students and families who want a better education for Portland’s youth, Yondr’s negative impact has vastly outweighed any positive effects. It has resulted in a significant level of distrust in Cleveland’s administration, isolated students with unsettled peers, and drawn even more attention to the other problems that define student life at Cleveland. The fact that many major, underlying issues have been ignored rather than addressed with additional sizeable grants, leaves us with the impression that PPS cares more about attendance and graduation rates than the actual benefit that education is meant to yield.