The Power of Music

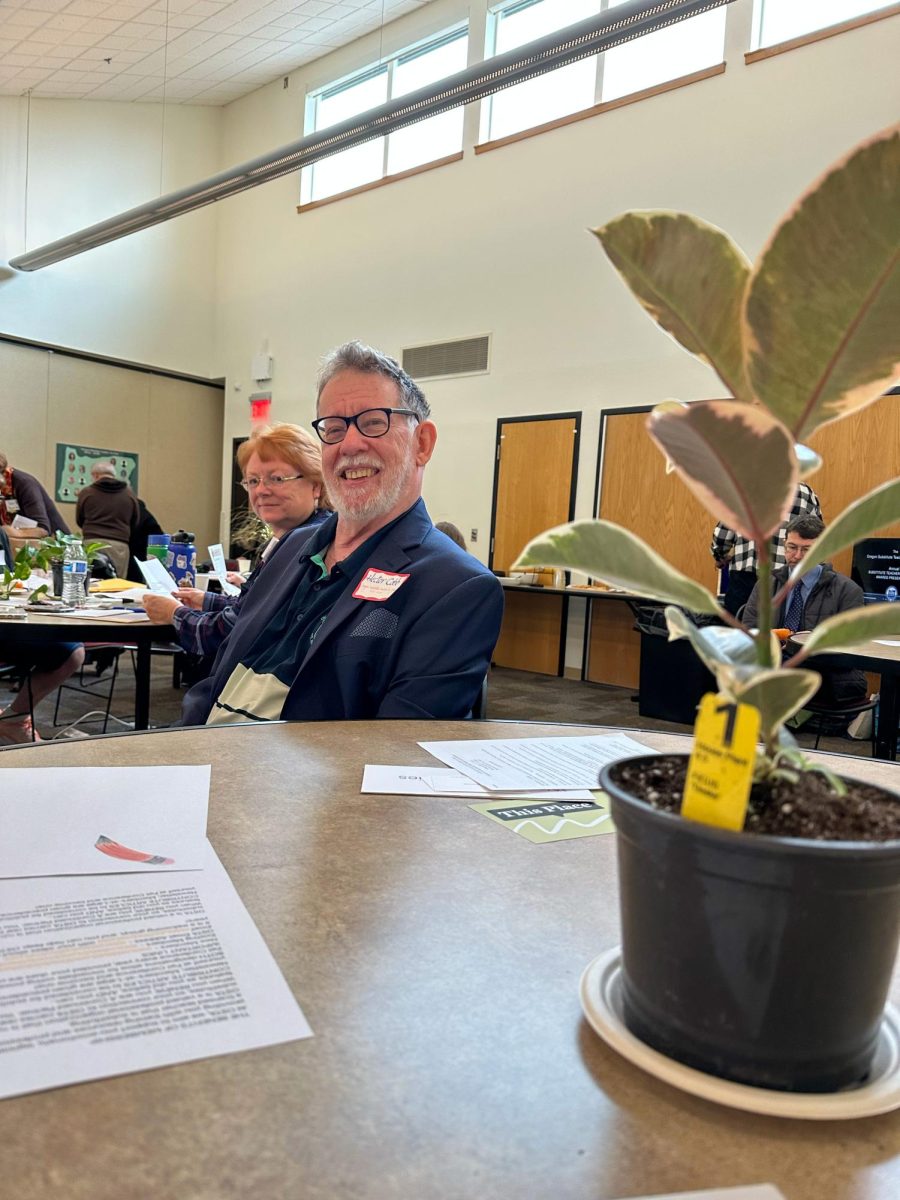

Clarion photo Ian Legros

“Music gives me a lot more to do. It allows me to meet a lot more people and it’s a way to express myself. It definitely lifts my mood and is a stress reliever. It is also really inviting to play with others because everyone around you is supportive. I always feel free to just play as loud as I can.” -Micah Lytle, sophomore

March 11, 2016

Those piano lessons you’ve taken since you were six years old? The mornings you spend singing in the shower or blasting out to your favorite music in the car? The recorder you learned in fourth grade? All these activities have profound impacts on your health and affect how you act, feel, and think on a daily basis.

Many people are aware of the benefits of music to one’s mood and emotions. However, listening to and playing music can do so much more than that. Research has found that music has healing powers and can improve memory, work performance, exercise ability, and more.

What happens in the mind when one listens to music? In recent years, brain imaging techniques have shown that listening to music activates various regions and improves cognitive functions. It can activate the brain’s motor regions—which prepare for physical movement—and motor and limbic regions, involved in emotion and memory. It also improves spatial ability, speed of processing, and creative problem solving for a short time period (approximately 10 minutes).

In 1993, Rauscher et al. created a term known as the “Mozart Effect.” She claimed that listening to Mozart’s sonata for two pianos for 10 minutes can increase one’s spatial reasoning skills. The results of her study showed that the main spatial IQ scores were 8 and 9 points higher for subjects in the music category compared to subjects who listened to relaxation instructions or sat in silence.

Later, however, her theory was somewhat disproved. Instead of simply classical music, researchers found that music improved cognition if it was meaningful to the listener.

Vice Principal Katy Wagner-West, who received a Bachelor of science in psychology, music, and pre-medical studies and taught choir for six years, said, “Everyone comes to music with a lot of different experiences and has their own personal music preferences. That is not to say that classical music is going to improve your cognition and make you smarter. It could be for those people in which classical music is most meaningful for them. But others may have an effect from a different type of music that resonates with them.”

Music can also facilitate the recall of information and past experiences. Frank A. Russo, PhD, associate professor of psychology at Ryerson University, said, “Enjoyable music may lead to dopamine release in the mesolimbic (reward) pathway, which may in turn support the formation of associations and, ultimately, memories.”

Actively playing an instrument can have even stronger effects. Today, some evidence suggests that musical training may enhance one’s reading and literacy skills, spatial temporal reasoning, mathematical abilities, and emotional intelligence.

A study published in the journal Neuropsychologia shows that playing music can improve working memory. Musicians outperformed non-musicians on standardized tests of visual, phonological, and executive memory.

Practicing music can also lead to neuroplasticity, which is the brain’s ability to change and form new neural connections. After only 15 months of training in early childhood, playing a musical instrument has shown to provoke structural changes in the hippocampus—an area involved in learning and memory—and improve motor and auditory skills.

“When you make music, it engages many different areas of the brain, including visual, auditory and motor areas,” said Gottfriend Schlaug, a Harvard Medical School neuroscientist. “That’s why music-making is also of potential interest in treating neurologic disorders.”

“There is research that shows that more activity occurs in the brain in a band and choir student than any other class in the course of a day,” said Gary Riler, band teacher.

Furthermore, making music can aid people in multitasking. Musicians were 30 percent more accurate than the non-musicians when performing two tasks at once according to a 2014 study by psychologist Melody Wiseheart and her colleagues at York University in Toronto.

Music has also found to be healing. It helps restore speech and motor functions in stroke patients, stimulate memory in people with dementia, and aid children with autism in acquiring social language and motor skills. There are even people who are unable to speak—formally termed nonfluent aphasia—but some therapists have noted that these people can still sing.

“Music-based therapies seem unique in their capacity to tap into emotions, to help the brain find lost memories, to let patients resume their place in the world,” wrote Willian Forde Thompson and Gottfried Schlaug in the Scientific American Mind Article titled, “The Healing Power of Music.”

Besides from academic improvements, music can also benefit one’s physical fitness, as it increases physical capacity and arousal to improve performance. A study in the International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology found that carefully selected music can have performance-enhancing benefits during high-intensity exercise. It often reduces the feeling of fatigue, increases levels of psychological arousal, and improves motor coordination.

Researchers are only in the beginning stages of understand the science behind the healing and academic powers of music. Nevertheless, we know today that it can have a profound impact on one’s overall health.

Music is what Steven Pinker, Harvard University psychologist, calls “auditory cheesecake” and what Albert Einstein said gave him the “most joy in life.”

So next time you are playing your exercise playlist or listening to music as you do homework, remember the numerous benefits it has on your mind and body. It may just push your grade one letter higher and motivate you to run the extra mile.

For further reading about how music affects well-being, read the novel “This is Your Brain on Music,” order Scientific American Mind’s issue on music therapy, or research other scholarly articles.