Progression towards equity at Cleveland

May 9, 2016

Reaching and sustaining equity have been problems throughout all of human history and have snaked their way into the halls of Cleveland. For the past few years, all faculty have been attending professional development sessions called “Equity Trainings” to better understand the current equity problems on campus and learn how to address and dissolve them.

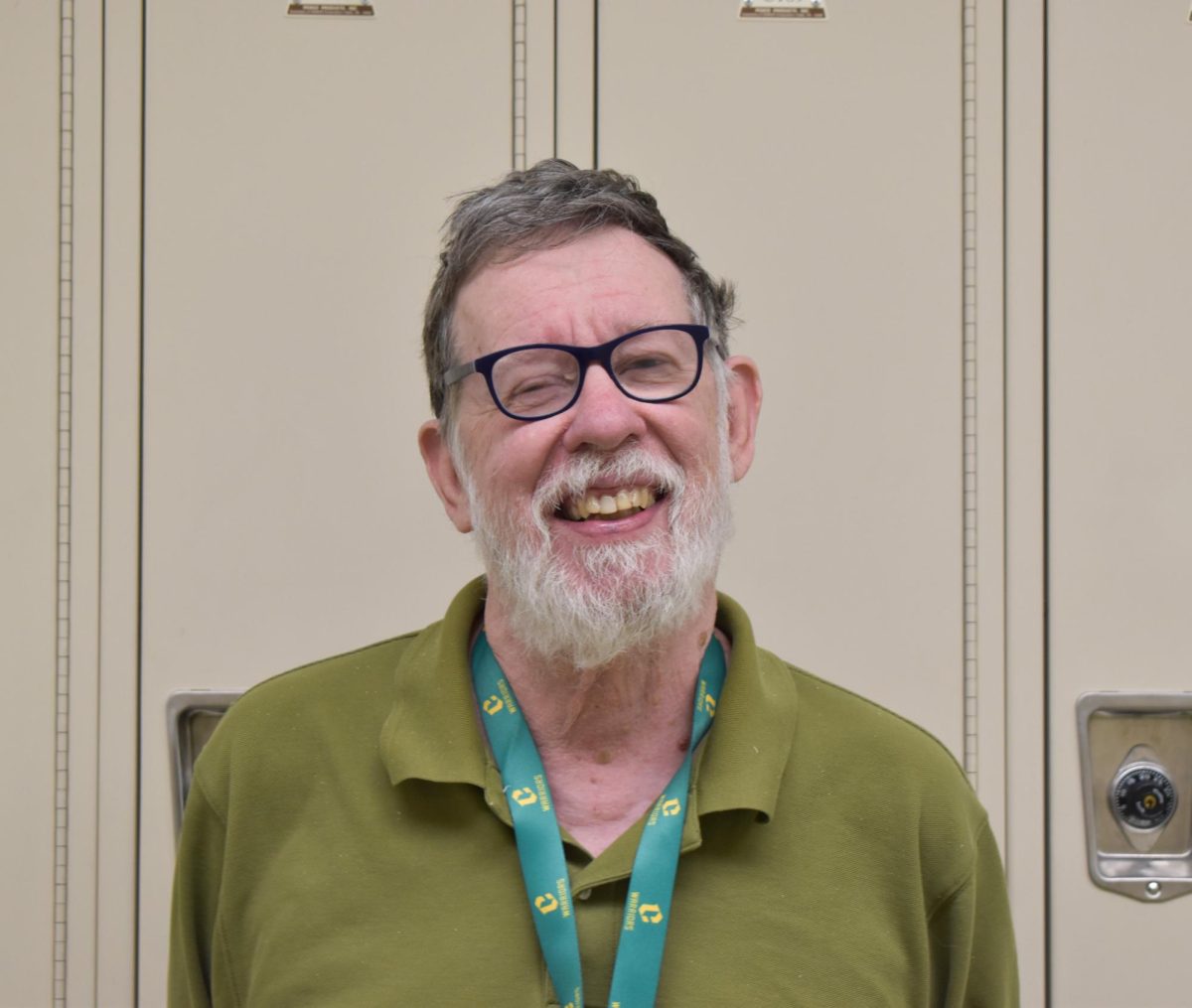

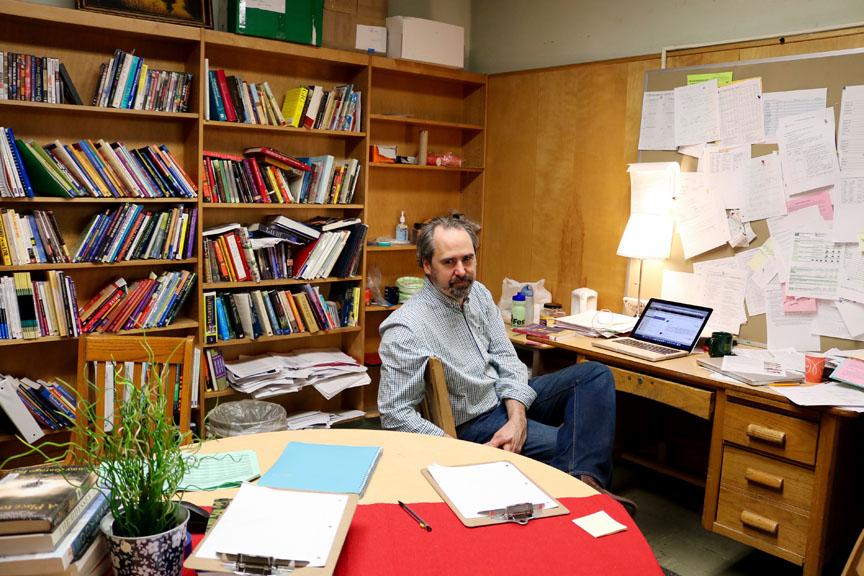

“Our main goal for the equity training is to ensure that all students have a teacher who is culturally responsive. In other words, they are responding to whatever needs the students have based upon race, ethnicity, [and] socioeconomic status,” explained John Golden, one of the equity team advisors.

This issue is deeply rooted in our society, a society that has always struggled hugely in the realm of fairness. There is no easy way of going about fixing the problems that we grapple with, but no good is done when we leave the problems to rot.

Vice Principal Darryl Miles is engaged in an equity misfortune because it is his truth. “Being an African-American male gives me some imput. My background in the equity problem itself is, I have experienced every problem that a black male could experience in the process of becoming an educator. I have experienced discrimination since I was born,” said Miles. He strives to establish connections between people so they are able to have empathy for their peers and put on the shoes of a student of color in a school so distinctly white.

According to the Cleveland High School website, 67.8 percent of students attending Cleveland are European American; that is a massive percentage.

“One of the issues Cleveland is facing is we have a very white teaching staff,” said Golden. “Sometimes we don’t always recognize that we are bringing our own cultural background into the classroom which influences the way that we teach … . It is important we recognize that and understand it.”

The goal is to create a space where students feel that the entire school population is aware of, understanding of, and supportive of their cultural differences and backgrounds. To achieve this, the staff and administration must help all students to access what they need in order to succeed.

Counselor Heidi Tolentino has been part of the equity discussion from the very beginning. She is a biracial woman and hopes that her perspective can be helpful in the process of talking about equity. “I think our biggest problem at Cleveland is that a lot of people don’t know there is an equity problem. Often it’s easy to pretend that there aren’t issues, that racism doesn’t exist here, and that we don’t have anything that we need to fix because of that. Until we get to the point where we can all agree that we do have a problem … I think it [will be] difficult for us to really move forward in becoming a better community.”

But, how do you teach equity? “A person can’t fix something if they don’t know it is broke,” Miles said. “We are trying to educate teachers in cultural awareness so they can be culturally sensitive to their students in their teaching.” This is a long process—and possibly uncompletable one—as the topic of race is a difficult one to concur.

Golden explained, “Teachers want quick fixes. Part of the tension and difficulty in these professional developments is that we want answers, we want tangible results that we can point to and say, if only I can do this, then this will happen. I think the reality is that issues around race and culture are so deeply embedded in our society that we have to expect and accept non-closure. In other words, we have to be OK realizing there aren’t quick fixes, there aren’t answers, there is not one strategy.”

In their meeting, they understand and act by these four principles: stay engaged, you may experience discomfort, speak your truth, and expect and accept non-closure.

Beginning in February, teachers began asking students of color who they knew well and had strong relationships with what they wanted to share with the staff. This led to the staff creating a series of questions about what they wanted to find out from these students. This list included, “Do you feel like you are treated differently because of your race?” and “Have you suffered any microaggressions or discriminations based upon race or ethnicity?”

“My experience was that the students were extraordinarily eager to share,” said Golden. “They wanted us to know what it’s like to be a student of color, what does it mean to be in an environment where you are one of few?” The staff was eager to listen, hoping that they could break through the blockades that stand in front of students’ learning.

Through the student voice interviews, they found that some students of color felt “separate and ostracized” from their own fellow students.

To begin this transformation to a culturally accepting space, we must start at the base of education, the educators. “[We are asking staff] to look really critically at themselves and really critically at their practice, to put their personal beliefs and ideas out there for people to hear,” Tolentino described. It is a daunting task that must be taken to excite change.

Another issue found by inequity is the achievement gap that is congruent nationwide. Cleveland’s students of color perform worse than its white students. What does the equity problem look like at Cleveland? “It looks like there are not enough students of color for people to be concerned about,” said Miles. “We have an 85 percent graduation rate. Who makes up the 15 percent that are not graduating? Special-ed students, students of color, and students of poverty. And my goal,” concluded Miles, “is to cut that 15 percent down as much as we can.”

The teaching staff and administration have gone above and beyond in their efforts towards finding equity at Cleveland. Speaking to the work that has been done and what is ahead, Golden acknowledged, “I don’t know to what extent we will be able to solve these larger societal issues about race and class, but for our little spot here in Cleveland, the teachers are fully engaged, so positive and so supportive of the work that maybe, in our little spot at Cleveland, we can.”