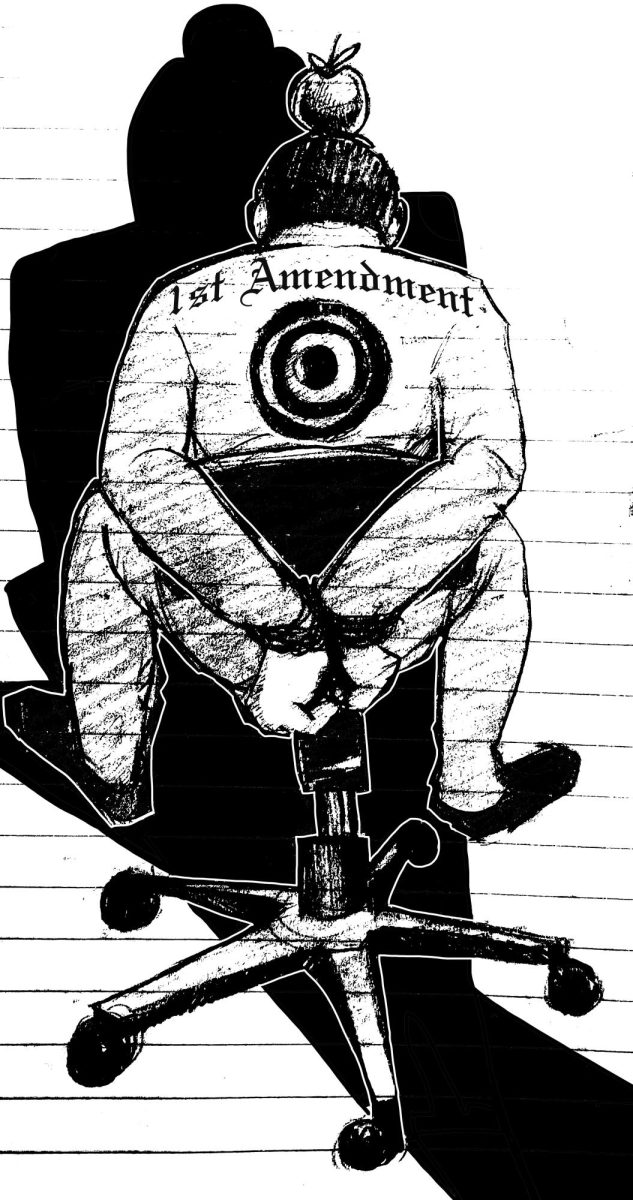

Debatable: Student’s rights

Clarion photo Colin Stevens

October 5, 2016

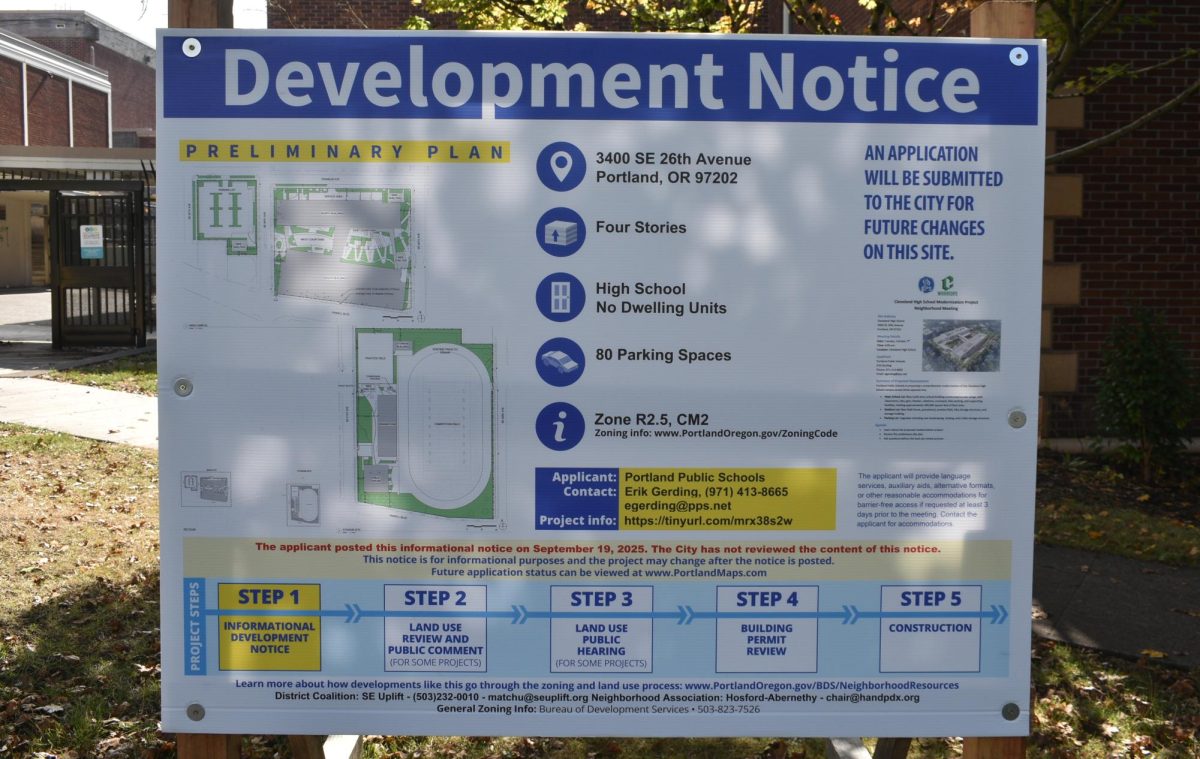

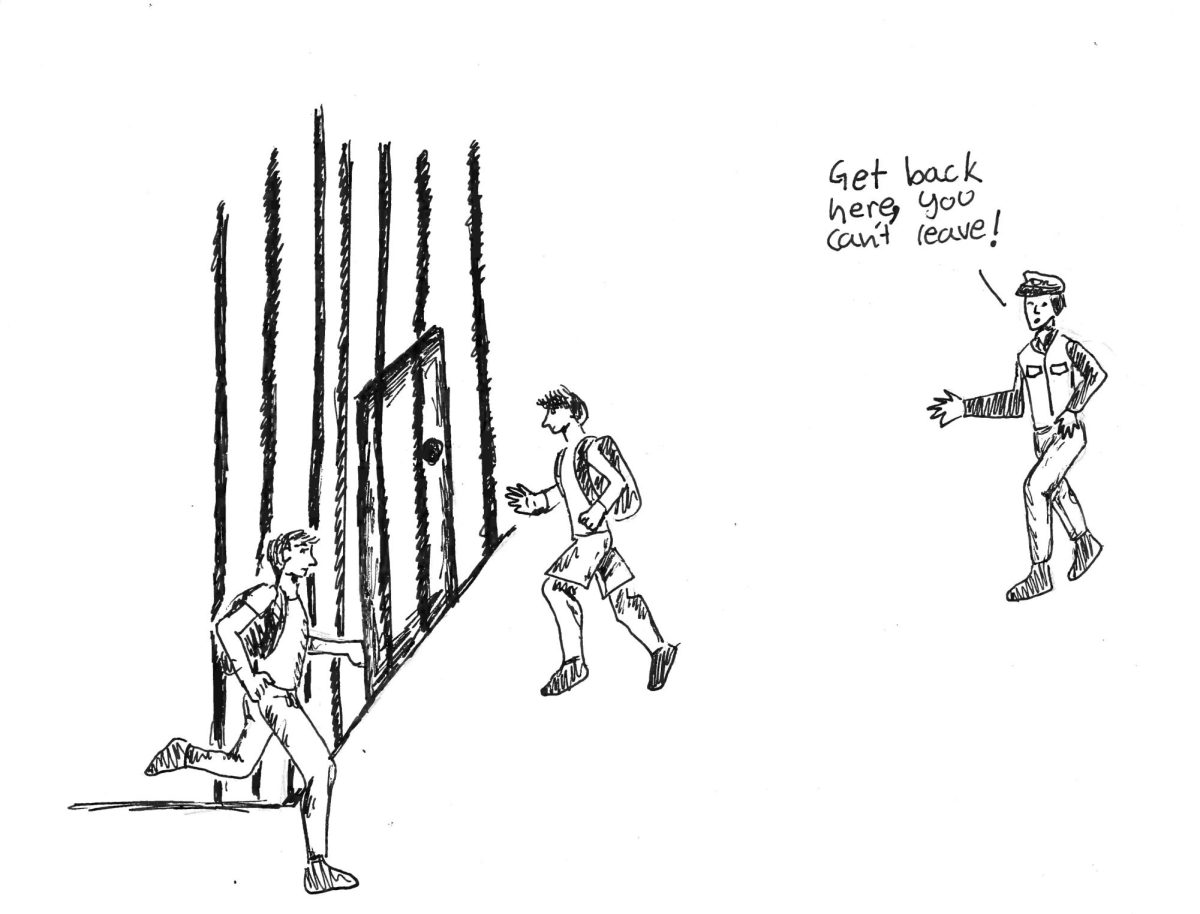

A few weeks ago, Lincoln students conducted a walkout to protest the district’s decision to postpone placing a $750 million dollar bond measure on the ballot that would have gone to rebuilding Lincoln, as well as both Benson and Madison high schools. During the walkout, Lincoln students changed course where the 1,000 plus students would attempt to recruit those attending Benson by entering the school. Many attending the school expressed wishes of also joining the protest, yet when the protest arrived, they found a scene of armed guards at locked entrances. The explanation offered by Bob McKean, the interim PPS superintendent, was that the lockout was for the safety of everyone involved, and with more notice accommodations might have been able to be made. Although this claim was legitimate (Benson was in no way notified of the march, and was far unprepared for the increased capacity) it leaves us to question if a school’s responsibility of safety, can legally outweigh the student’s First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

Like many at Cleveland, I recently received a thin blue book titled “Student’s Responsibilities, Rights and Discipline Handbook.” For all my knowledge, it was the same as last year, and every year prior since my entrance into the PPS system. They could have just been changing the dates at the bottom and most of us would be none the wiser. As it was being passed through the aisles of my psychology class, I heard a chorus of groans. We knew what lay inside, and none of us seemed the least bit excited. I was about to throw it in my backpack, eventually to be shoved under a pile of college spam mail at home, when one a friend asked a question that gave me pause: “Since when do we have rights?” It was a fair question, and soon we started flipping through the pages. Finally, we found the pages dedicated to Student Rights, but something was off. Everything listed was requirements and behavioral rules from the dress code to attendance. Under the main title there was – in small print – “and responsibilities,” which we had missed before. Apparently the only rights worth mentioning were the five on the previous page. They took up maybe a quarter page, and were hopefully obvious by 2016 (two of them being the right to talk/report to administration).

The U.S. Constitution generally applies to everyone under the law, regardless of religion, race, age, or gender. However, the one group that the Bill of Rights fails to protect is minors. Unlike adults, those under 18 can be subject to a much more restrictive set of rights. Proponents of these laws argue that maturity is critical to decision making. They believe that 10 year olds simply cannot be expected to make the same level of decisions as adults. Thus the latin phrase and legal term of loco parentis is applied. The basic idea is that while a student is in custody of a school, that school can and should step into the role of the parent. The other reason lies in the primary goal of a school, which is to educate. When a student interferes with the learning process, that action may also be repressed.

Although some of these restrictions on student rights are necessary, many people bring up the unconstitutionality of such limits. Under loco parentis, previously guaranteed rights such as unwarranted search and seizure or freedom of expression laws are not applied. There is, in fact, very little discussion on locker searches. Most courts would agree that because lockers are school property, there is no need for a warrant. To this extent I would agree, however, there are many other instances where student rights need to be recognized. Just as 10 year olds can’t be expected to make the same choices as adults, students in high school should not be considered in the same position as 10 year olds. In addition, schools should not be able to hold high school students against their will, especially if their freedom of speech is involved. Schools are institutions of learning, not prisons (as much as it would sometimes seem), and should recognize that students being politically active is one of way of increasing that academic literacy. Instead of sweeping restrictions on rights, I would propose the laws to be relaxed as one moves through the education system. In the coming years, we should expect for the right of education in schools to be in conflict with the rights of privacy and speech. Which will win? In the end it’s all debatable.