STEM: Should We Emphasize Math?

December 12, 2017

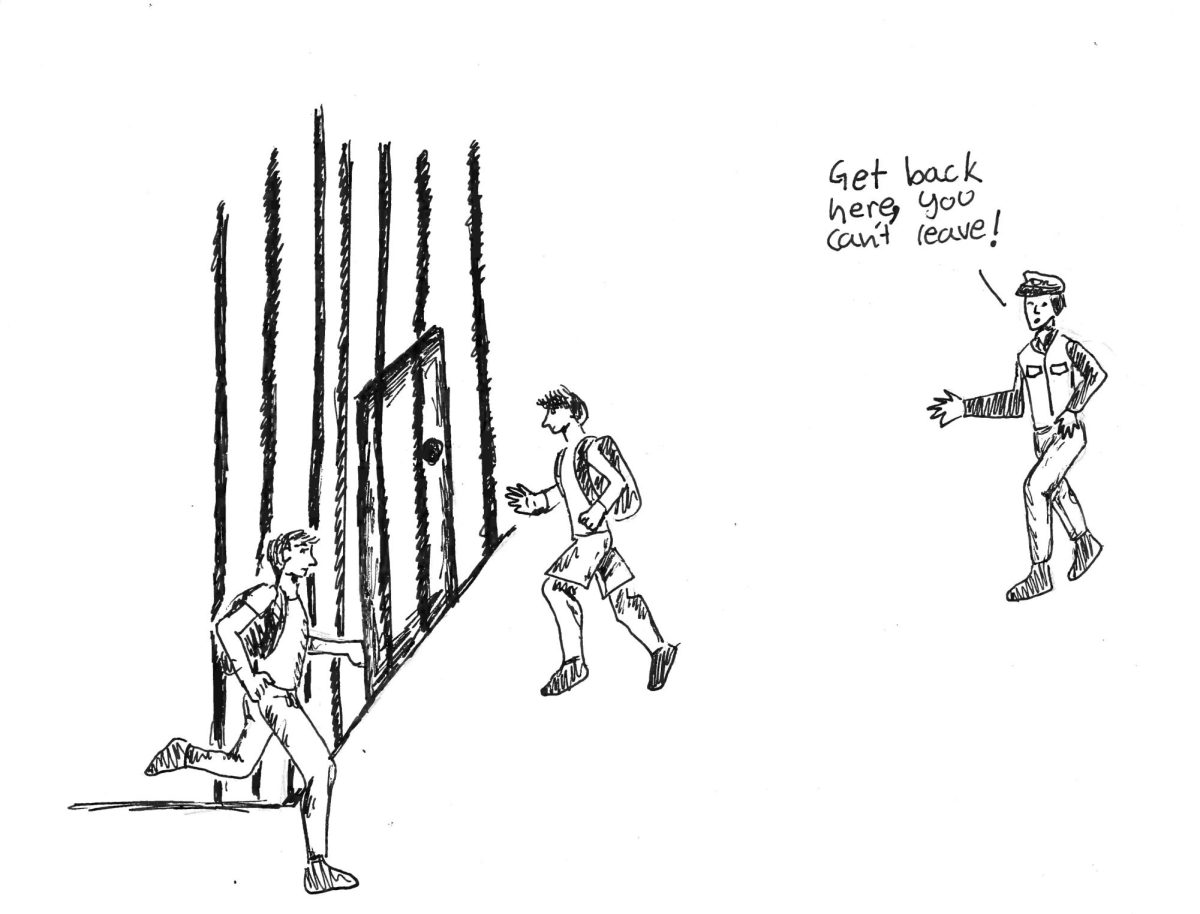

As my ideas of a future job evolved, my parents’ reactions were very interesting to note. When I wanted to be a mathematician? Perfect. An engineer? Even better. A physicist? No questions were asked. But when I suggested my current inclination towards psychology, my dad suggested that I investigate the world of mathematical psychology and my mom agreed because she’s always thought I’ve had a mind for numbers. While I do admit that I probably like math more than the average teenager, my interests have strayed farther and farther away from the world of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math). But that hasn’t stopped my parents from asking about my mathematical enthusiasm, something that reflects a greater concern of the U.S. as a whole: that we are falling behind the rest of the world in the STEM department. While that worry can certainly be justified, I don’t agree with the emphasis on STEM in this country because it creates a vicious circle.

The ever-increasing STEM fervor can be attributed to the direction the global economy is moving in and what jobs are becoming popular. The two jobs projected to have the greatest increase in employment by 2026 are solar photovoltaic installers (105% growth) and wind turbine service technicians (96% growth). Other STEM-related occupations that are among the 20 fastest-growing are statisticians (+33%), software developers (+31%), mathematicians (+29%), information security analysts (+28%), and operations research analysts (+27%). Because the future seems to lie in having an interest or a passion in STEM, that is what is being emphasized in education, which makes sense. In regards to what is happening in the U.S., it’s not so much an issue with priorities as it is with the results.

Test results are the principal source of the national concern about STEM in this country. The U.S. has become accustomed to being at or near the top of the world in many aspects, but test outcomes is not one of them. One of the ways to compare the educational systems of countries around the world is the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). It is an exam given to 15 year olds in 72 countries every three years, which tests their abilities in math, reading, and science. The most recent one was in 2015, with 540,000 students participating. In science, the U.S. averaged a 496, 25th in the world and barely above the worldwide average of 493. Math was worse, with the U.S. managing a 470 average, which was in the bottom half of the list (38th) and well below the international average (490). These two scores raised alarm and indicated to American educators that math and science needed to be significantly improved. It was another reason why the U.S. students needed to work extra hard to catch up with the rest of the world. But this zeal to get on the same level as other countries may in fact be the root of the problem.

One may begin to question the elevated importance of STEM when they start paying attention to things other than job growth or test results. Three countries who consistently ranked in or near the top ten were Finland, Estonia, and Japan. Why did they do so well in math and science when none of them prioritize a STEM education like the U.S. does? The answer could lie in how they educate their students. I chose to study Estonian education last year in Theory of Knowledge and was surprised at how balanced and comprehensive their education system was, especially pre-university. For example, students are required to study two foreign languages in addition to Estonian, which include English, Russian, German, French, Finnish, Swedish, Japanese, Spanish, and Hebrew. In science, they are required to take biology, chemistry, and physics, as well as a separate nature studies class. The arts aren’t neglected either, with a music class, an art class, and handicrafts and technical studies integrated into every stage of their education before going off to a university (primary, secondary, and high school). It seems that Estonian students are exposed to a wide range of subjects from a very young age, which gives them a broad view of the world and a balanced education. I find it interesting to note that this is also a goal in the U.S. (especially the part about having a broad global perspective), but it doesn’t feel like there’s much of an effort to accomplish it. We’re focused on catching up to other countries in STEM by promoting studying it, but we may be ignoring the reason why those countries do so well, namely that they give their students a more varied education. Ironically, we might be our own worst enemy when it comes to STEM.

So is an all-encompassing education the answer to improving math and science scores? Even if that isn’t the obvious answer, it is pretty clear that pushing the STEM fields in this country hasn’t yielded amazing results when compared to the rest of the world. I wish our education would be more diverse because math, science, and technology aren’t subjects that everyone loves or would want to do for a job. Besides, if you have balanced knowledge, you probably are more prepared for whichever direction the world goes in and have more options for your future. It doesn’t take much mathematical or scientific analysis to figure that out.