The Perils of the Model Minority Myth

February 27, 2018

Bill O’Reilly, a political commentator and news anchor for Fox News, challenged the idea of white privilege on August 24, 2014. He made the assertion Asian privilege was the problem permeating America, and then made the assumptive connection that whites had a disadvantage to Asians. Citing the Bureau of Labor Statistics, he found that “The median income for Asians, close to $69,000 a year; it’s 57,000 for whites, [and] $33,000 for black[s]…” His claims and statistics allude to a common status placed upon Asian Americans by white institutions called the model minority myth.

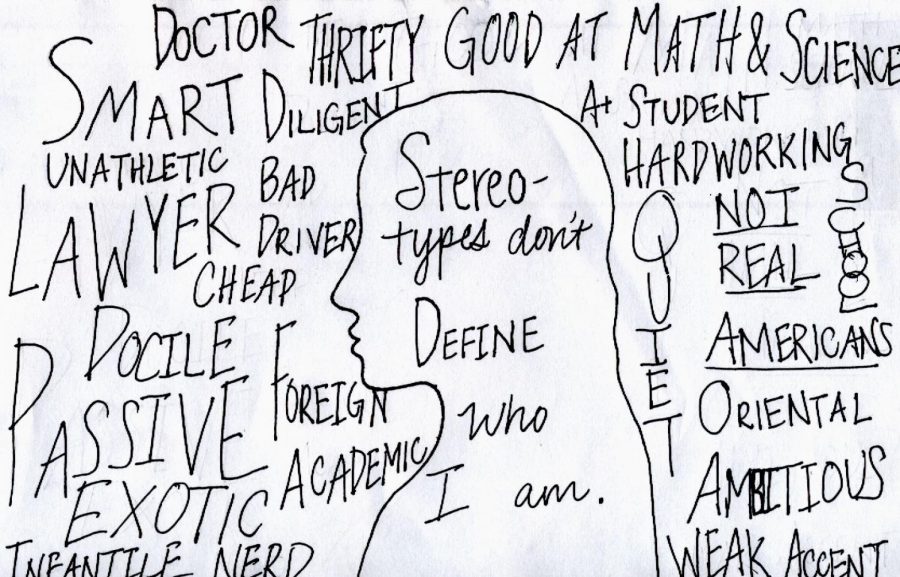

The model minority myth refers to the idea that a racial minority group will achieve high levels of success in contemporary American society. This title is supposed to be a compliment to those of Asian heritage, characterizing them as hardworking, high achieving, and well behaved. But even these positive traits can have a detrimental effect on both Asians and other communities of color.

In January of 1966, the term “model minority” was coined by American sociologist, William Petersen, who wrote an article for the New York Times magazine titled “Success story: Japanese American Style.” Petersen praised Japanese American cultural values and their obedience in comparison to African Americans. He went on to state that their cultural and family values prevented them from becoming a “problem minority.” This article was considered one of the most influential stories written on Asian Americans, and gave birth to the phrase “model minority.” At first this term only applied to Japanese Americans, but then extended to anyone of Asian heritage.

However, white Americans did not always think highly of Asian Americans. America in the 1800s had a large influx of Asians immigrating to the U.S. during the California Gold Rush. Later they aided the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, and worked in agriculture. In the 1860s, the economy fell, and whites were in fear of losing their jobs. Whites placed the blame on Asian Americans, and called them “heathens” who stole their jobs and raped their women. This was known as yellow peril: the xenophobic theory that people of East Asian descent are a threat to the Western World. Following this outcry of fear, Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, banning all Chinese citizens from immigrating to the United States.

After years of exclusion and discrimination, the Asian community residing in the United States in the early to mid 1900s faced an upward mobility in education and started receiving higher pay than African Americans. Many thought this was due to the rising quality in education for Asian Americans. According to a study done by Nathaniel Hilger, Asian Americans’ education did not significantly change. His research suggests that in actuality Asian Americans were earning more because their white counterparts became less discriminatory toward them in the workplace.

Ellen Wu’s book, “The Color of Success,” explores the origins of the model minority stereotype and its use during the Cold War and 1960s civil rights movement. Wu writes that in order for Asian Americans to shed negative stereotypes about them, they assimilated to American culture in order to achieve respectability in American society. During the Cold War the United States touted the Asian American success story in order to propagate America’s status as a country of freedom for all. About 20 years later down the road, during the Civil Rights era of 1960s, whites continued to positively portray Asian Americans as a strategy used against the African American community to deny them rights. It was a method to blame African American for the oppressive conditions they were living in.

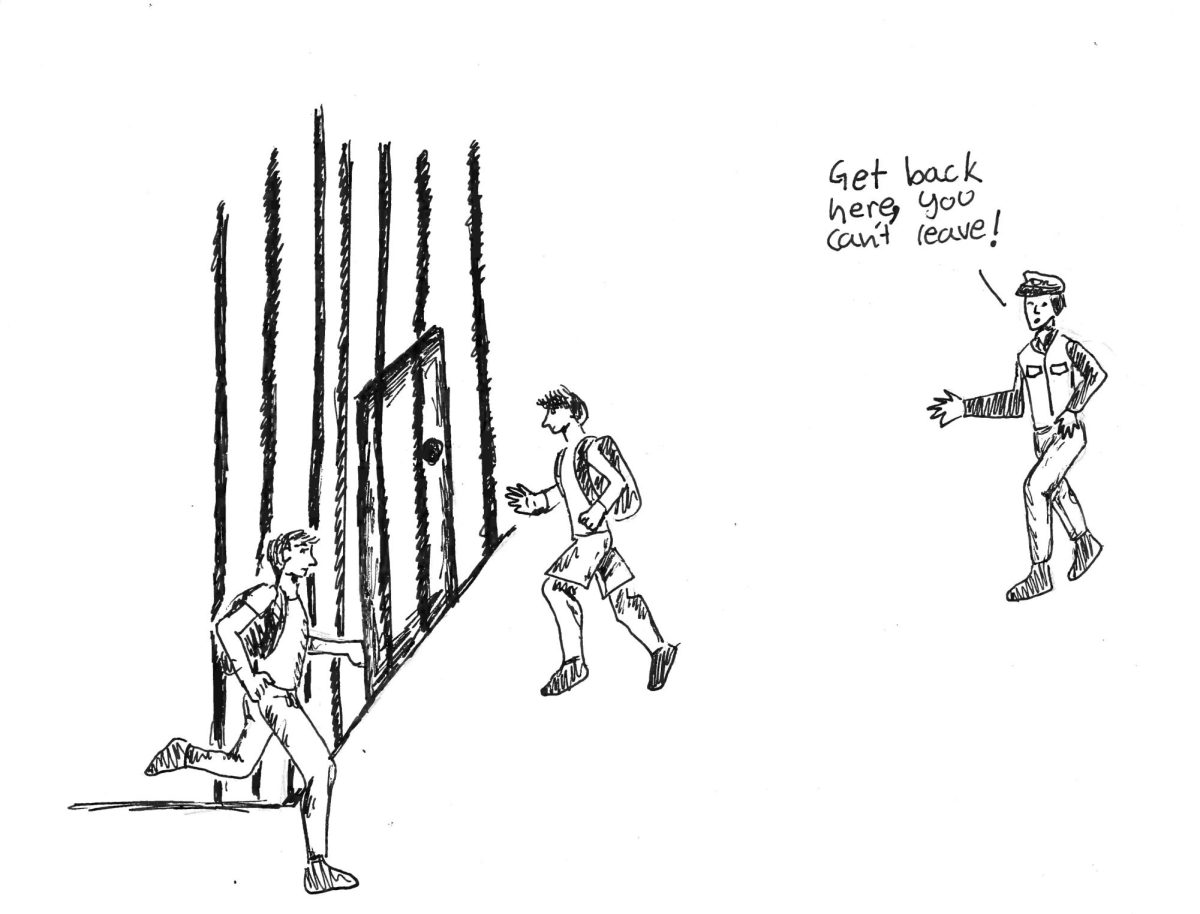

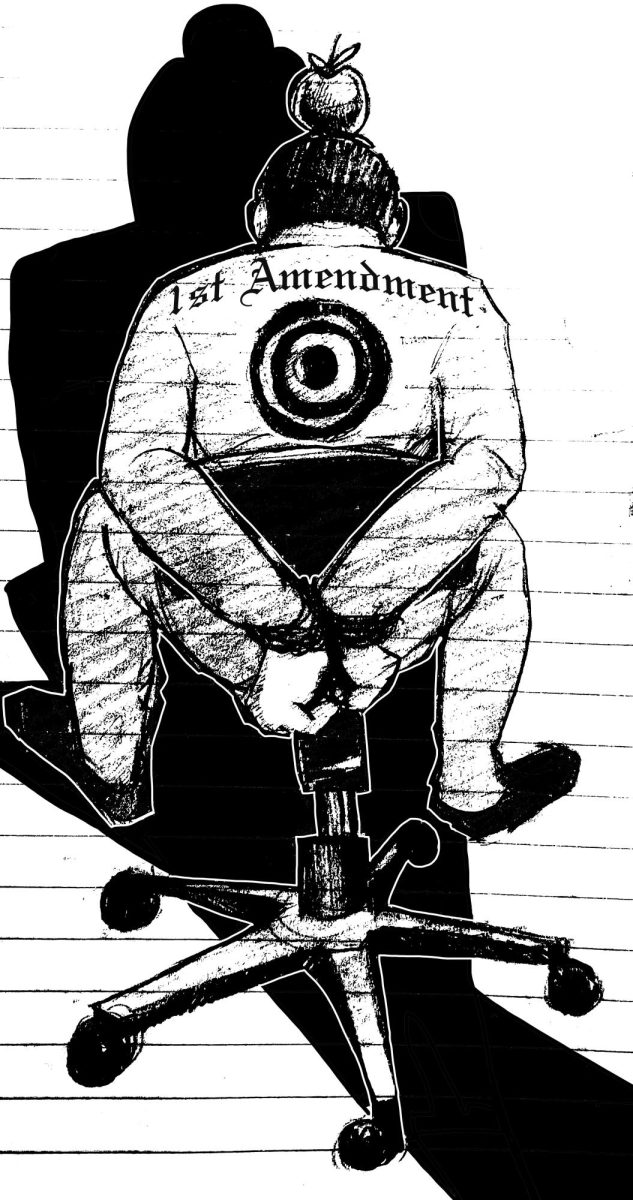

Even after 60 years from 1960, the model minority myth is still very prevalent in the lives of Asian Americans. As an Asian American myself, this derogatory stereotype is becoming more apparent in my everyday life. I never realized how much power I gave this stereotype to dictate my life. Being forced to conform to these racially-based expectations felt like a betrayal to who I really was. From a very young age it was implied for me that being academically diligent (only in mathematics and science), quiet minded, and studious was the only way I could gain social acceptance from my fellow Asian peers and approval from white and Asian teachers. As a result, it led to insecurity and self-deprecating thoughts about my value as a student and person, since I did not fulfill the role of the model minority.

Tiffany Vo, junior, voiced her disdain for the stereotype as well. “[This stereotype has] definitely affected the way I behave and think and the way I enter a space. For me it’s especially [obvious] when I’m the only person of color in a classroom or just anywhere,” Vo said. “I feel like for a lot of Asian Americans, not to speak for all of them, there is this specific image that we need to uphold. When I step into a room as a person of color… I’m afraid to make mistakes and fail, and this myth reinforces that.”

When any stereotype is forced upon a group of people, it can harmfully impact how a person internalizes these preconceived notions while coming of age. Senior Veitanah Chang recounts upon his experience growing up as he tried to fit the role of what being Asian meant to his family. “… the idea of model minority and Asian stereotypes in general is extremely pervasive and dangerous; having definitely affected and influenced myself. I can definitely remember times growing up where my mother and her sisters (who raised me, and were first generation immigrants) told me about and tried to mold me into that very same stereotype: the ‘perfect student,’ studious, academic, and obedient, all of which I’m definitely not,” he said.

Vo remarked how this stereotype, no matter how positive, can have a malign influence on those it attempts to categorize. She remarked, saying, “No stereotype is positive even if it puts you in a good light. Stereotypes were put to categorize people, and to even demonize them and alienate them … .”

Chang went on to also comment on his intolerance to the manifestation of racial stereotypes and their influences on society and culture, saying, “Stereotypes, specifically [about] minorities, are inertly rooted in racism and confirmation bias. Saying that anyone is “just like” a stereotype is quite rude and offensive to the individual. Any [racial] stereotype is bad, racist, and reflects the society we live in.”

The model minority myth not only attempts to generalize all people of Asian descent, but also criticizes other communities of color, reinforcing their inferiority. Frank Wu, professor of Asian Studies, further explains how the model minority myth can be a different form of oppression toward other peoples of color. “From the very beginning, the model minority myth has been false flattered. It’s not even really about people of Asian descent. It’s a way to insult African Americans, Hispanics, and others. The model minority myth has always been used as propaganda as a way to say, ‘Yes, we applaud the Asians.’ But really what we’re doing is denigrating other racial minorities.” White Americans that believe in the model minority myth utilize it as a tool to subordinate other racial groups by asking them, “If Asians can find success in America, then why can’t you?” Wu concluded.

White systemic institutions have a vast history of pitting other communities of color against each other. This symptom of a Eurocentric society has caused some to disbelieve the detriment racism has caused for various racial groups. Andrew Sullivan of the New York Magazine wrote, “Today, Asian-Americans are among the most prosperous, well-educated, and successful ethnic groups in America … . It couldn’t possibly be that they maintained solid two-parent family structures, … placed enormous emphasis on education and hard work, and thereby turned false, negative stereotypes into positive ones, could it? It couldn’t be that all whites are not racists or that the American dream still lives?” In his article, “Why Do Democrats Feel Sorry for Hillary Clinton?” Sullivan disregards that these disparities are the result of systemic racism. His commentary, like Bill O’Reilly’s’, reflects the ubiquitous influence stereotypes have on people of color and the hierarchy it forms among racial communities. The model minority myth has created a wedge between communities of color in order to dilute the problems of racism. This divide between Asians and other racial groups can prevent them from working together to strip away these stereotypes.

Though common Asian stereotypes prevail, Asian voices are being heard more often in attempt to deconstruct racist ideas people still have. More news outlets and Asian activists are starting illuminate the Asian American experience, expanding on what it means to be Asian, and how race should not limit individuality and personhood. As more Asians express their experience being labeled as a model minority, we see them rejecting the myth as something that defines their identity.

We need to do more than just listen, Vo suggests. She said, “We need visibility and understanding and compassion. I think we have good conversations, but I’d like to see some action. [People] don’t bring into the equation that there is this new generation of Asian Americans that are ready to fight and are not going down.”

Society’s silence on Asian American voices has dwindled, and the uproar of newer voices has yet to be heard. Asian Americans like me are quickly learning that being Asian does not require us to be docile and subservient. It requires us to use our race as an avenue for empowerment and advocacy for others.