Cleveland Dance Team Changes Name to “The Sun Dance Team”

November 26, 2018

Two years ago, it was the annual homecoming assembly. Students cheered for their classmates atop the gym bleachers. Excitement filled the air as the announcer said, “And here are your Sundancers!” Everyone applauded as the dance team rose from the sidelines. Everyone except then sophomore Nia Williamson, and then junior Larae Ellenwood. Williamson’s heart stopped at the announcement. Discomfort sat between them as they watched on the sidelines.

Now a senior, Williamson, and graduated student Ellenwood have pushed for Cleveland’s dance team to change their name from The Sundancers to a non-Native affiliated name since 2016. Finally this past June, the dance team officially changed their name from The Sundancers to The Sun Dance Team.

Chloe Gustafson, The Sun’s senior co-captain, cited her reason for the name change, saying, “We changed our name to The Suns because it was brought to our attention that it was insensitive to the Native American population at our school, and we wanted to help start the movement of changing names that are seen as offensive and insensitive.”

Additionally, Connor Carr, senior co-captain, said, “I think that was important to us just as a part of the Cleveland community, because sports teams names represent our entire school, and if we’re representing those who are offended by our name that’s not right.”

The Oregon Board of Education in 2012 prohibited schools from using any names, symbols, and/or images that replicate any Native American customs or traditions. Cleveland’s former dance team name was The Sundancers, which referenced a private and sacred Native American ceremony. When the 2012 dance team first heard of this news, the coach petitioned to keep the name because of the new identity they had imbued the name with: positivity in dancing around the sun. PPS allowed them to preserve the name because of the coach’s argument.

The Clarion picked up on the request for a name change and reported in 2016 that the team’s volunteer coach, Criss Burgess-Haneberg, commented on the former name. She is the mother of head coach Coral Burgess, and has been involved with coaching the team since 1978 when Cleveland’s mascot was the Indians. Criss Burgess-Haneberg said, “When the change from Indians to the Warriors was made all the names were reviewed and the Sundancers was determined to be ok. The sun belongs to all of us, not one ethnic group. We just focus on the fact that the sun is bright and sunny and we dance. I have as much right and so does the team, and so does anyone, every race of people. To us as a team, it has never had anything to do with something strictly Native American.”

When Cleveland changed its mascot from the Stenographers to the Indians in 1948, it began a long history of appropriating Native American names and customs. The mascot eventually was changed in 1988 from the Indians to the Warriors, and the newspaper from the Tomahawk to the Clarion, for example. Though Cleveland attempts to erase its theme of cultural insensitivity, there are still subtle remnants of Native American appropriation.

Williamson is from the Nez Perce tribe. Ellenwood, her cousin, is of Blackfoot, Nez Perce, and Seneca decent. Both students met in the fall of 2016 during Williamson’s sophomore year and Ellenwood’s junior year. Williamson said, “I was the only Native student that I knew, and so when my cousin came… we validated each other’s experiences.”

Traditionally, the Nez Perce Tribe does not participate in Sundance. Williamson said, “My great grandfather during the Nez Perce War fled when he was 12 and ended up in one of Sitting Bull’s camps. He pretended to be Sioux so he could hide from the government. My tribe doesn’t do Sundance, but because they gave my grandfather that ceremony, he took it back to our people and shared it with our family. That’s why we do Sundance, to repay Sitting Bull and his tribe.”

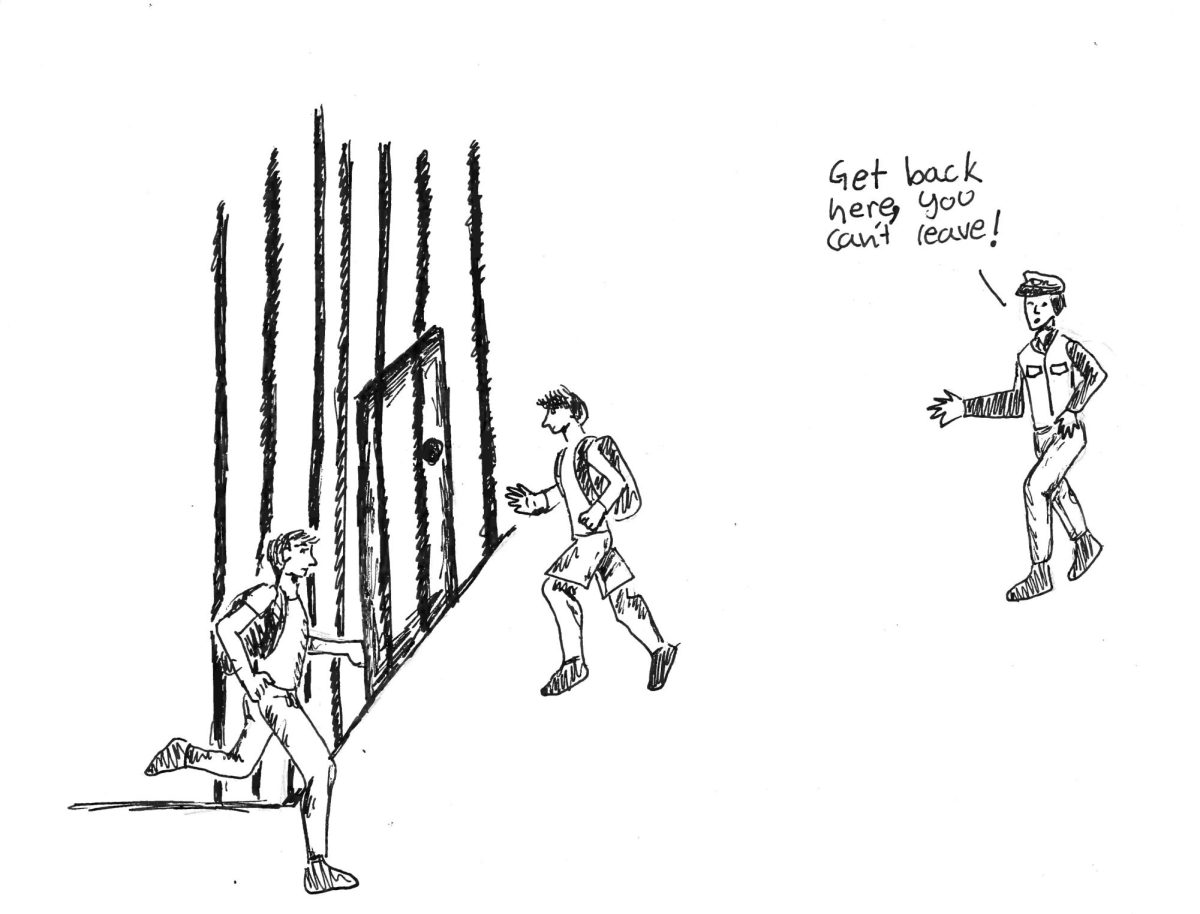

Ellenwood and Williamson decided to bring forth their concerns with the old name with former Cleveland principal Tammy O’Neill, and subsequently initiated a plan to change the name within a couple months. Though, after O’Neill left Cleveland, neither Williamson or Ellenwood had contact with the dance team for a whole year, putting the process on hold.

Conversation around the old name surfaced again during Williamson’s junior year and Ellenwood’s senior year. In March of 2018, Williamson and Ellenwood agreed to discuss the name The Sundancers with the dance team. Generally, the team was ready to take part in changing the name, but a few older team members felt a sense of identity and attachment with the old name.

“I think there were differing views on the team, especially older members that were a little bit more wary about it,” Carr said, “but I think we had a lot of discussions about it and meeting with a couple of the students that are Native American at our school opened our eyes. It’s one of those things that is in our control, but also is at a district level that had to be changed so that’s why it took so long for the change to happen.”

After meeting, the dance team intended on collaborating with Williamson and Ellenwood to choose a new name. Williamson was upset by this request because “they wanted [Larae and I] to represent all Native people… . I don’t think it’s my position as one Native student at this school to collaborate with the entire dance team to find a name that isn’t offensive. What I would recommend is they reach out to the local Native communities, specifically the Native American Youth and family Center (NAYA).”

According to Ainslie Cromar of the Portland Tribune, Coral Burgess submitted three new name ideas to the Director of Indian Education, Angie Morrill, who reviewed the names for traces of cultural appropriation. Coach Burgess hoped for The Sun because of the identity the team had associated it with. “We have spent decades dancing for the sun,” she said.

As of this school year, the team will be using the name The Sun Dance Team. Gustafson felt optimistic about the new name. She said, “I feel right now is a really big time for change, especially around cultural appropriation and insensitivity. Other teams in Oregon know our symbol as the sun, and so we didn’t want to lose our symbol.”

The dance team wants to make Cleveland a community where students, staff and administration can have productive discussions. Carr said, “This year especially is such a great year for conversations and trying to make this community as respectful as possible. I think that this year was the year it needed to happen. I think our new name is great because we get to keep that presence with our team without culturally appropriating another group’s identity.”

Principal Ayesha Freeman stated that she did not want Cleveland to continue appropriating some students’ culture. Sh said, “We don’t want any of our clubs or athletic teams to be cultural appropriators, so by removing The Sundancers as the dance team name—and instead being called The Sun Dance Team—my hope is that we don’t want to dehumanize and be disrespectful.”

Despite the team’s willingness to change the name, Williamson is unsatisfied because she claims the new name, The Sun Dance Team, is just a variation of the The Cleveland Sundancers.

“I think the fact that they change their name from the Sundancers to The Sun [Dance Team] is really reflective on how the school deals with equity and inclusivity issues, and how in the rest of the world white people treat people of color. They say what you want them to say, like, ‘Oh, I’m sorry. This is something we need to start talking about and people need to start getting educated on these things.’ And then when the time actually comes, they do the bare minimum. If their goal was inclusivity and starting conversations, I think they failed in every aspect with this new name. To me, it still contains that demeaning part from an identity that they claim is their own, but in reality, is someone else’s.”

Cleveland’s lack of racial diversity has caused the school to oftentimes overlook or dodge issues surrounding equity. “This school is not as racially diverse. With that in mind the school and students and administration alike need to realize what equity means,” Williamson said.

Principal Freeman added that she would like to aid in amplifying student voice at Cleveland to enforce equity. “I think one of the things that I’d like for us to do is to have culturally specific clubs and affinity groups where we’re hearing from our students from historically underserved backgrounds and students of color about what are their experiences that are positive and negative, so we know we can do as a school to help those experiences that are negative. I think the number one thing we can do is have places where students have voice… and I would love to hear that feedback.”

Creating an inclusive and comfortable space for students of different historical backgrounds is one of the first steps. Williamson said, “Even though I see signs that say, “All Are Welcome No Matter Race, Gender,” it’s obvious that people don’t really understand the difference between equality and equity. Since [this] school used to be the Cleveland Indians and used to have a theme… all of that left over is not going to go away. You walk into this school and there are little bits of microaggressions everywhere. To move forward we have to not only confirm that they’re there, we also have to learn how to overcome them as a whole versus telling individuals to overcome them themselves.”

As Cleveland continues to replace and change former Native names, Williamson is advocating for the school community to educate themselves on the history of Native Americans locally and nationally. It is imperative that we do more than discuss; we must act on those conversations and create just change.