Homework Does Not Work

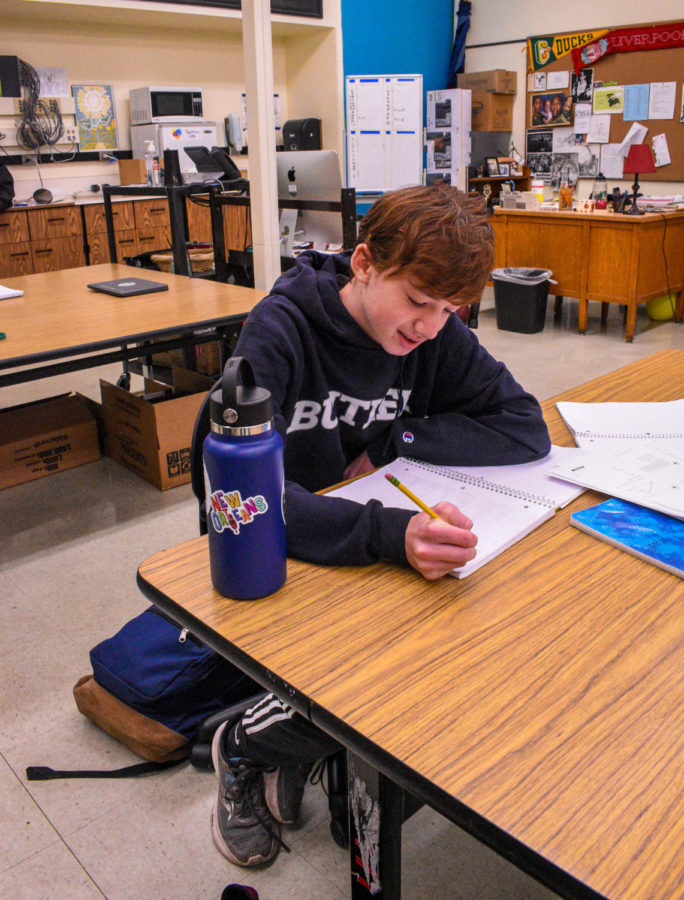

Students try to balance their school work and life outside of school

“Homework is inequitable.” That’s certainly an uncommon view, especially from a teacher. But Cleveland High School teacher John Golden is firm in his beliefs, seeking to significantly decrease every student’s workload at Cleveland.

Golden is an English 1-2 and 10th Grade Inquiry teacher who has chosen to stop assigning homework to his students.

“I started focusing more on the outcomes that I want students to demonstrate rather than the process or focusing too much on the process,” he said.

Golden believes that not all students have enough time or ideal home circumstances to complete all of their homework on time without sacrificing most of their free time.

A surprising number of students do not have reliable access to WiFi or a desk to work at. Some have responsibilities to take care of siblings or must work to help support their family.

Golden had his fair share of negative experiences with homework when he was in high school.

“I would either cheat on it, I would have my friends do it, I’d copy it on the way in, or I just wouldn’t do it,” he commented.

Despite this, for the first 18 years of his 28 year teaching career, he assigned a plethora of homework to his students.

“I just assumed for years and years that I just had to do it because that’s what was expected,” he said.

Many teachers assign homework just because it is the norm and fail to think about the reason for assigning it. Going against these common expectations is difficult, so when Golden first stopped assigning homework, he was worried that people would think his course was not rigorous.

Golden has found that he is able to cover enough content for both of his classes in the allotted class time.

However, Golden believes that some homework has a valid purpose. He argues that homework that is connected to real world topics or serves as practice can be helpful. In world language classes, there may not be sufficient time to reach standards or even fluency within the bells.

As important as practice may be, “We can’t grade it because it’s not equitable. We’re not going home to the same places.”

Not all teachers share Golden’s views. Cleveland IB Physics teacher Rafael Bobenreith has some similar and different experiences with homework.

“I’ve taught classes where I realized really quickly homework was going to be counterproductive…but I’ve also been in other settings where I recognized that homework was absolutely necessary,” said Bobenreith.

Bobenreith has found that the IB curriculum covers far too much for students to complete in class free of homework.

“Do I just throw everything and make students do a lot of homework that we just can’t cover in class? Or do I not cover it at all and just make them aware that you know, hey, on the IB exam, this is a topic we didn’t cover in class,” he complained.

Even though Bobenreith assigns plenty of homework, he does not penalize late work. Like Golden, he believes that students have busy lives and do not always have the time to complete all of their homework by the due date.

However, he makes sure to remind them that getting behind might affect their learning journey.

“If they haven’t done the homework prior to a class and…the class is based on them having done it, then they’re going to get less out of that lesson,” Bobenreith argued.

These homework dilemmas arise with the IB Program, something IB Coordinator Jennifer Wiandt Owens is an expert on.

Wiandt Owens has worked at Cleveland for 23 years and seen first hand how homework can affect students.

“[IB Diploma students have] a three hour average each night for the five nights of school,” she said.

The homework is meant to help prepare students for college, but Wiandt Owens says that the workload and class difficulty of senior students seeking an IB Diploma can exceed the workload and class difficulty of first year college students.

With all of this, students still have enough time to pursue their personal interests outside of school, according to Wiandt Owens. In fact, pursuing personal interests is actually encouraged.

Wiandt Owens wishes that the IB program would be a little less difficult for students, so they have a healthier balance between school and personal life before the intense years of college.

Even though IB is popular now, it has not always been so mainstream at Cleveland.

“We’ve come to recognize that we didn’t want it to be a separate program that some students were in,” said Wiandt Owens.

Instead of having IB as an option for more difficult classes, Wiandt Owens believes that IB is for everyone. Due to this realization, the administration has been transitioning Cleveland into an “IB for all” school over the past several years.

“Anything that’s a graduation requirement in junior and senior year…are IB classes for everybody,” said Wiandt Owens.

The change to an “IB for all” school increased the gap in the amount of homework to a gaping chasm between grades 10 and 11.

Sophomore Alex Valliere is not excited for this leap in homework as he prepares for his third year at Cleveland.

Valliere is already part of Cleveland’s Constitution Team, an honors history class which focuses on learning and debating about the United States Constitution. Constitution Team has a reputation for being one of Cleveland’s most intense classes, assigning large amounts of homework after every class.

Valliere is also a member of Cleveland’s Cross Country team, which means he has significantly less time to work on homework.

“I do cross country, which is like basically two hours, so I get home at like six,” he said.

With little time to work on homework for other classes, Valliere argues for decreases in homework workloads at Cleveland.

Not everyone at Cleveland agrees on how much homework to give, but it is certain that many students and even teachers want changes to be made.

I'm Finn, and I'm currently a Junior at Cleveland. I run for Cleveland's cross country team, and I enjoy hiking and backpacking in my free time.