Colleges are collecting information about you

December 1, 2015

It’s no surprise that data mining prevails over a large and profitable part of the digital world. Of course, tracking a consumer’s technical footprint doesn’t seem so unusual from a big box store. But would you expect such intrusive and presumptuous behavior from colleges that you have not even shown interest in?

Every person who has taken the PSAT, SAT, ACT, or registered with the College Board can expect a flood of emails to come their way in the ensuing months. Even knowing this, it is shocking to find out that these enterprises sell your personal information to marketing companies hired by colleges for 37 cents a pop and make millions doing so, according to Inside Higher Ed. Even more bewildering is the idea that these seemingly innocent emails are tracked by highly sophisticated data mining systems and generate reports on students that are sent back to the colleges. As listed by the New York Times, these accounts include extensive information about you—that you opened the email, where you were when you did so, what device you were on, various details about the device’s operating system, how long you looked at the email for, how many times you viewed the email, and if you saved, forwarded, or deleted the email. This practice, while clearly an invasion of privacy, is perfectly legal.

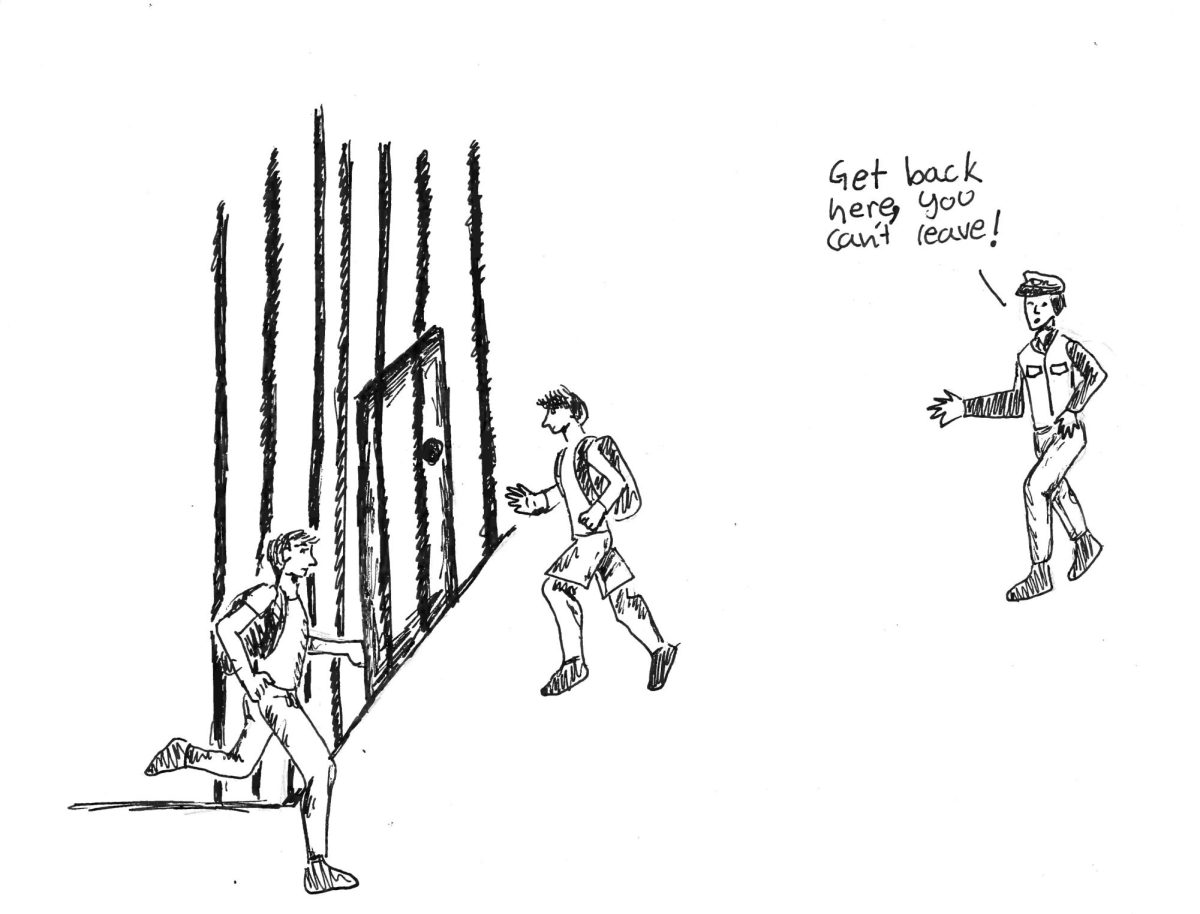

This information is then compiled into online profiles for each student. If an individual is caught “demonstrating interest,” which can mean something as little as opening an email, the school will continue to spam your inbox. It should be made clear that these emails are not sent directly by the college in particular—they are sent by marketing agencies that the school has hired.

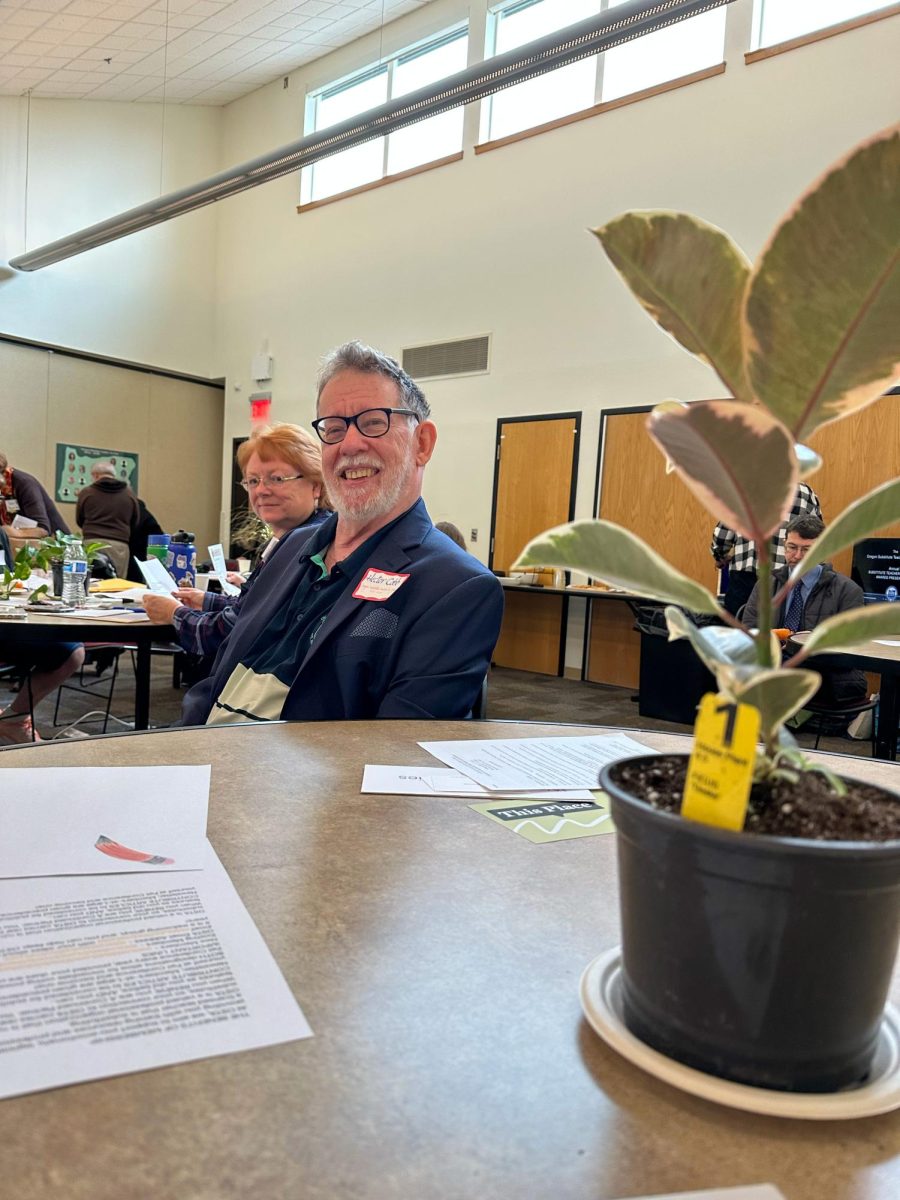

So why would a college go to all this effort for a student who hasn’t even shown that they are interested? “It all has to do with the yield,” said Emily Standish, college admission coach and Cleveland CCC volunteer. “Yield” is a mathematical term colleges use to describe the percentage of students who enroll out of the number who are accepted. For instance, if 100 students are accepted into a school, but only 50 enroll, that school has a 50 percent yield. Colleges use this percentage to calculate how many students they need to accept in order to reach their target number. This number also correlates with the number of students a school needs to attract in order for a certain number to apply. This prediction system allows a college to indirectly control their acceptance rate to increase their appearance of prestige and selectivity. Evidently, the primary vessel in which colleges attract students is through advertising. The mountain in your inbox and the stack of letters in the recycling from colleges you didn’t request information from have thus been explained.

In some cases, schools will also check up on students’ social media. A student following a school on Instagram or Twitter or liking them on Facebook is also considered by many schools as “demonstrating interest.” This is more common with athletes than regular applicants, as admissions officers and coaches will “proof” a student’s social media for any “inappropriate behavior.” Many applications also require athletes to list their social media handles. While this isn’t as applicable to the average student, it should be mentioned that anything that appears to be “private” online can be accessed, and therefore should be kept spic and span.

Clearly, schools are willing to go to drastic lengths to uncover students’ “demonstrated interest.” Perhaps the most intrusive platform in which they have practiced these methods deals with a very private subject matter: financial aid. On a FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) inquiry, a student is required to list any colleges of interest (not consecutively) in order to receive information back about financial aid packages. Up until this year when the federal government outlawed it, schools had access to this list and made judgments about students by the placement of the schools on the application. These assumptions had been known to affect the application process. While this is now illegal, the scar is still prominent.

“All this business, all this game about opening the emails and looking at the FAFSA—looking to see who put you first—it’s all about colleges figuring out how many students are going to show up on campus in September,” said Standish. Big public universities and “name-brand” schools don’t typically take these measures, she explained, because they have a pretty set number of applicants. Smaller and lesser known schools have the burden of worrying about tuition, a challenge that bigger colleges don’t face. These are the primary reasons why advertising is so heavily relied upon and why schools are willing to go to such drastic lengths to get students’ attention.

As for social media, Standish explained, “Every time you put something online, it’s public. The only way to be private is to have nothing online.” Standish says she recommends to all of her clients, “Keep your social media clean, so if a college is inclined to look, you have control over what they see.”

Whether tracking students’ emails is intrusive or intuitive, one thing is certain: your privacy in the digital age will be compromised.