Proficiency-Based Grading: Something to Jump For or Cry Over?

Clarion photo Picasa

Overloaded. Steampowered photo.

December 3, 2015

The Debate: Proficiency-Based Grading vs Traditional Grading

It’s difficult enough for a student to navigate through high school, but when adding two clashing grading systems to the mix, it’s like jumping out of an airplane naked without a parachute. That is, a literal nightmare.

There has been much debate in recent years over infiltrating proficiency-based grading into our current traditional system. School districts have considered if proficiency-based grading could be the answer for improved learning within students. On the outside, this grading system appears to be polished, clean, and a primary candidate for solving the problems we face with the traditional system, although there is little evidence to back these claims. And though it is apparent that traditional A-F grading is littered with drawbacks, most Cleveland students have made it clear that they are not ready to mandate the use of proficiency-based grading.

What is Proficiency-Based Grading?

Since there are so many different versions of proficiency-based grading in use, it is extensively difficult to define exactly what it is. Essentially, proficiency includes a grading system in which students advance upon mastery, not upon receiving a passing grade like is seen in traditional grading. Proficiency is founded upon very explicit and measurable guidelines that communicate learning objectives and support based on individual progress. According to the PPS website, the goal of this grading system is “to give students, teachers, and parents an accurate picture of a student’s progress in mastering the Oregon State Standards so that teachers can provide the specific supports or acceleration each student needs.” This also allows a lot of room for student betterment. “The beautiful thing about [proficiency-based grading] to me is that it gives a student multiple opportunities to improve to be successful,” said Vice Principal Darryl Miles.

The Problems with Proficiency

While proficiency-based grading has gotten a lot of hype for its new ideals, there is not a lot of evidence to prove that it actually works in the classroom. Grades are also marked as “highly proficient,” “proficient,” and “not yet proficient,” thus wrecking GPA calculation in the case of district-wide use. Proficiency is currently weighed on a four-point scale, leaving little cushioning between grade benchmarks. Because this grading system has not been mandated, proficiency grades are translated to letter grades, for which are the source of GPA calculation. However, in the case of a unified switch, A-F grades would disappear, leading to no forum for GPA summation. Because of this, many students are concerned about college applications and about their grades not serving as an accurate representation of their skill level.

“[In proficiency] you only have option for three or four different grades, so it’s a hit or miss. There’s no in-between,” said Cleveland Student Body President Monica Arnone.

The Benefits with Proficiency

While proficiency surely has its ups and downs, many believe it to be the superior form of grading. “I like [proficiency] because it puts less emphasis on individual assignments and more emphasis on whether you actually gain the skills to succeed in the class. [That’s what] they’re trying to teach you over the long term,” said Kay Lowe, junior. Added Curran Chapman, senior, proficiency provides much more “wiggle room.”

With proficiency, outcomes largely emphasize the application and creation of knowledge, a core area that traditional grading seems to lack. This method of grading also allows for the development of important skills and provides a meaningful and positive assessment of individual learning. Senior Margaret Gibson said she liked proficiency-based grading specifically because of these diverse options. “I like being given the opportunity to truly learn the material, instead of only having one chance to show my comprehension,” said Gibson.

This type of grading also allows for a more stable connection between teachers and students. “Proficiency grading lets students have a more clear idea of where they’re at in class,” said Arnone. “There’s less confusion with percentages and teachers can really help students at the level they’re at.”

“Proficiency-based grading allows for a better understanding of the subject matter at hand when executed properly,” said Taylor Lewis, junior. “It often times allows for a better connection between the teacher and the learner.” However, he added, “When not done well, the relationship is often subject to increased tensions and decreased connectivity.”

Proficiency’s Inconsistent Nature

Certainly, proficiency-based grading allows students the option to improve their grade when administered the right way. Unfortunately, schools and districts do not oversee any overarching policies like is done with traditional grading, and thus it is primarily up to teachers to create their own grading procedures. Because of this, teachers have control over anything from designing their own grading scale, assignments, and exams to docking points for late work, missing work, and behavior. This has become a challenge for students because there isn’t a standard scale upon which all teachers grade their work. This can also be arduous for students who are looking to improve their grades. “It’s hard to get your grade up unless teachers offer retakes or extra credit,” said junior Alex Larson. “If they do, then I think proficiency grading is pretty fair, but if not then you only get one shot to get a good grade. If you mess up once, it ruins your grade.” According to English teacher, John Golden, extra credit is not even permitted with the standard proficiency system. “Extra credit artificially inflates what the grade itself means,” said Golden. “All it really does is add points, not demonstrate the learning.”

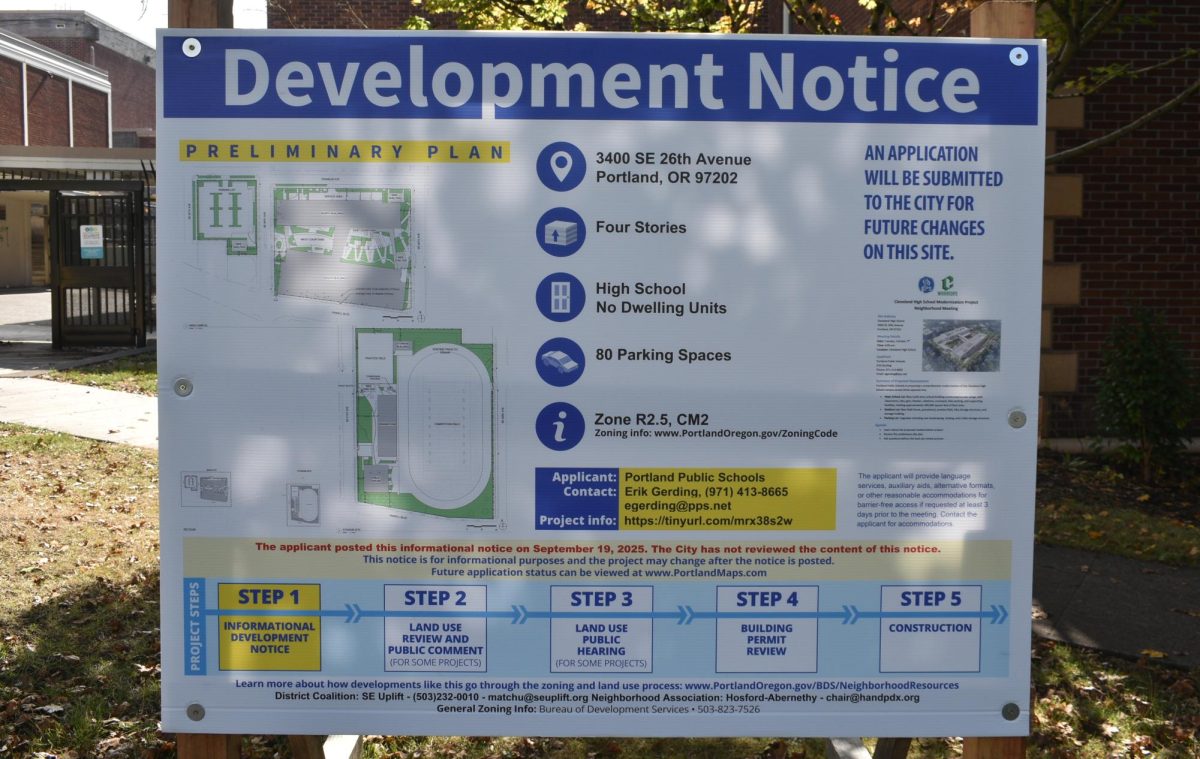

German teacher Roberta Stubbs is one of the six matrix teacher leads in the district. This is a position that helps with district Synergy (the electronic grading system teachers use for Student-Vue) and proficiency support within the school. “Almost all of the foreign language department is using [proficiency] this year. That’s six or seven,” said Stubbs. The problem, she stated, is that “there are 10 others in the building with a different version. They’re not using the ‘matrix version.’” This system is the basic template upon which teachers create their rubrics. While the matrix version should be the only system of grading found in classrooms that use proficiency, this is not the case. “I would estimate that there are probably between 60 and 70 different grading systems that are currently at work in Cleveland High School that students have to navigate,” said Golden.

This is perhaps the most troubling thing about proficiency-based grading—it is sporadic and inconsistent, with teachers using variations from the standard matrix version. This can be attributed to the fact that since it has not been mandated, teachers are free to revise their grading rubrics wherever they see fit. Most students agree that proficiency has the potential to be a great method of grading, though since it has no common basis, it is increasingly difficult to manage. Said Chapman, “There’s such a difference in the way teachers do proficiency. I like some of them, I don’t like others. In some ways, it’s easier and in some ways it’s harder depending on the styles of the teacher.”

To Mandate or not to Mandate: That is the Question

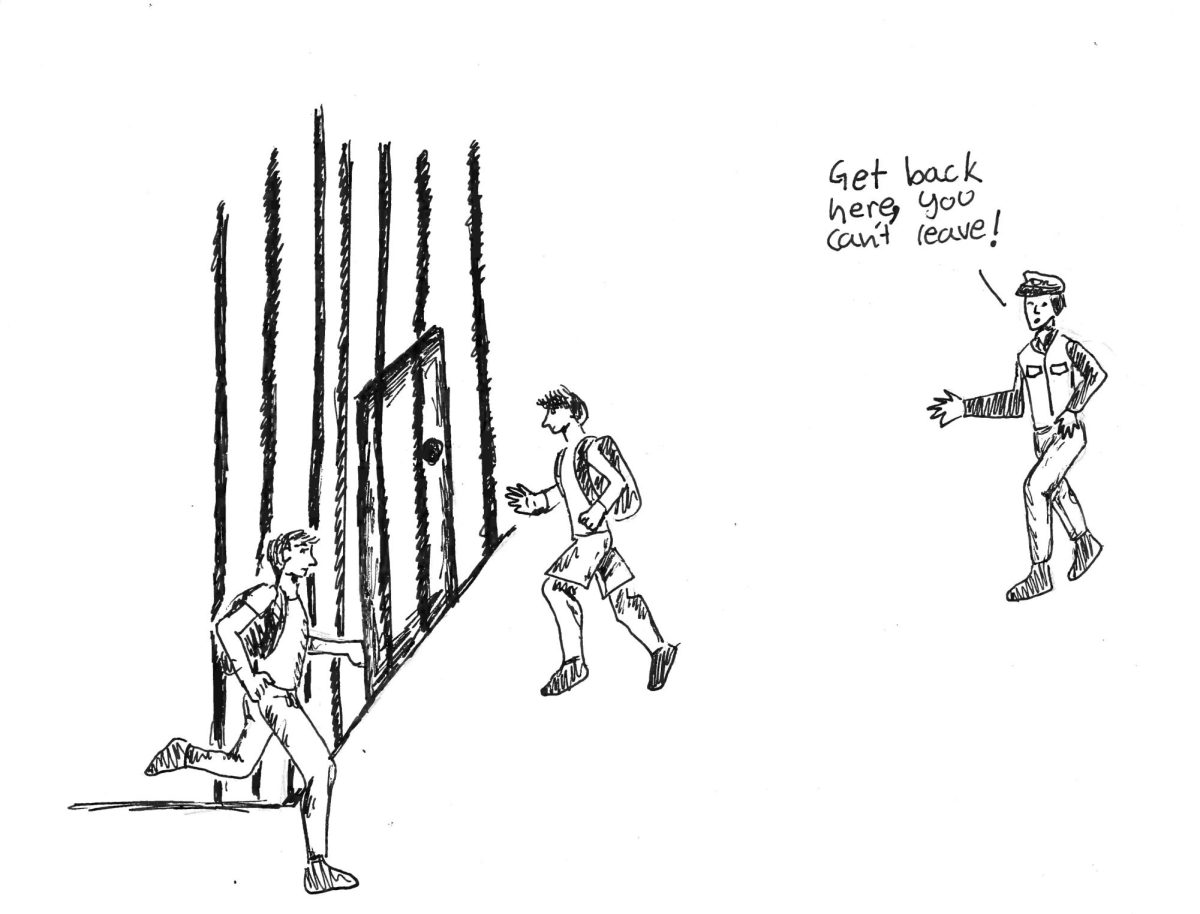

In schools that have tried using proficiency-based grading, like Roosevelt High School which recently mandated its use, many students have complained that they received little to no credit for homework, attendance, classwork, or extra credit—with proficiency, only tests, essays, and other assignments prove that a student has mastered a skill.

According to a Clarion hosted survey, only 25 percent of the student body said that they wanted Cleveland to mandate proficiency-based grading. The poll also found that around 64 percent of surveyors said they disliked proficiency-based grading.

“Schools that try to mandate proficiency typically fail,” said Golden. “We need teachers to come to it, not require, not mandate.”

Junior Amanda Kimball stated, “I think it should be a teacher’s choice [to use proficiency]. Some classes it WON’T work for.”

Even with all of the controversy, PPS has seriously investigated the switch to unified proficiency-based grading. While the district is not currently looking to mandate proficiency, it “is constantly considering what is beneficiary for students,” said Vice Principal Darryl Miles. The approach is also in progress within all PPS K-5 report cards and many middle schools, where academic achievements and behavior are clearly separated. In high schools, proficiency mainly presides over many math, world language, and science departments within PPS, already, though all subjects have adopted some form of the system. According to Golden, around one in four teachers currently use proficiency-based grading at Cleveland. This is not specific to subject area.

About mandating district-wide use of proficiency-based grading Lewis said, “Ultimately in the very end of that process, I do believe it would be a better system, but the route to that system would be long, laborious, and ultimately filled with pitfalls. I don’t think [change to proficiency] is a very good idea, and if we do do that, it has to be a slow change and gradual.”

Even with all of the controversy, PPS has seriously investigated the switch to unified proficiency-based grading. “I believe that one day there will be a day where we are a proficiency school, I just don’t know if it would be within the next three to five years,” said Miles.

“I would love nothing better than all teachers using the proficiency-based grading model,” said Golden. “However, there are a lot of things keeping us from getting there. Teachers need more time to plan, smaller classes and we need Synergy to be more reflective of what we do.”

Mixed Emotions

Cleveland teachers and students are still drastically conflicted on the topic of proficiency-based grading. While some wish to mandate it, others believe that forced use of proficiency-based grading will result in failure. Where some advocate for proficiency to be the future of grading, others think that it has no potential and is an inaccurate method of grading. It is clear that this controversy marks the dawn of changes within school grading systems.

Of course, all this discussion about mandating proficiency-based grading begs more questions than it provides answers. What would this potential change mean for college-bound students in the coming years? Is proficiency really the future of grading? Or is this controversial system really all it’s cracked up to be?