Part 2: Restorative Justice–A method to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline

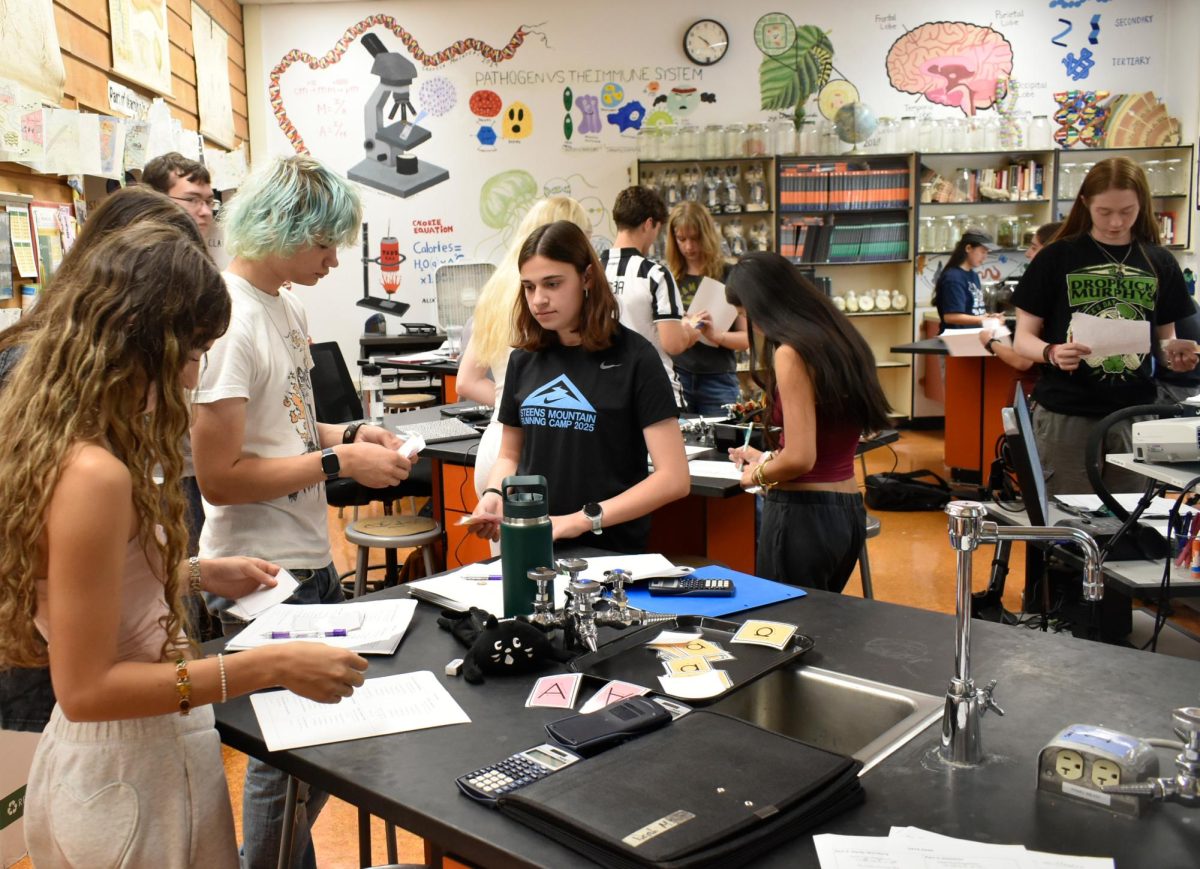

Clarion photo Cyrus Lyday

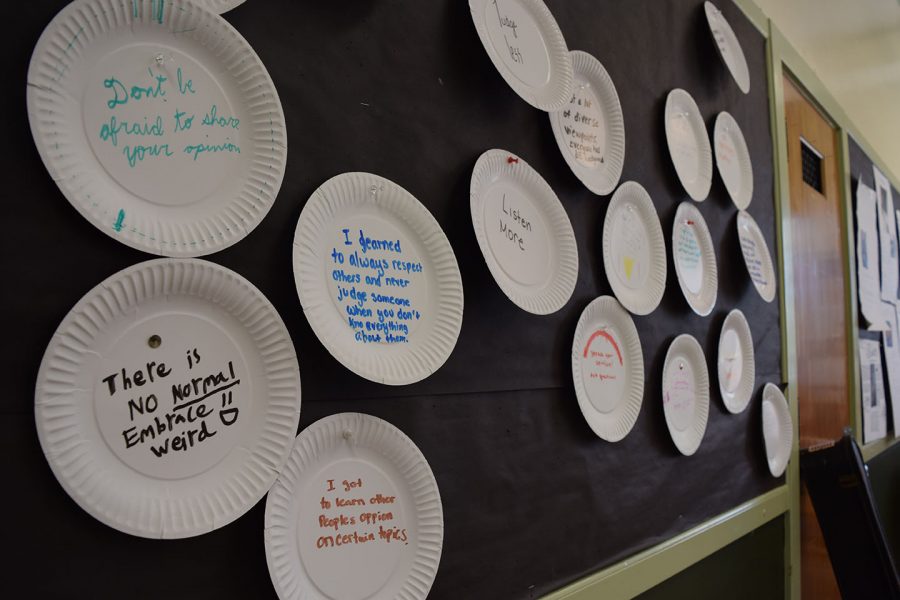

Students in Chinook academy reflect on their experience with Restorative Justice

April 13, 2016

In order to disrupt the school to prison pipeline, Hodge and Alexander introduced a discipline technique called Restorative Justice that has been shown to improve behavior.

“It is about making discipline conversation-based and non-punitive. It is also brings the victim and perpetrator together so they both can heal for the future,” Hodge said.

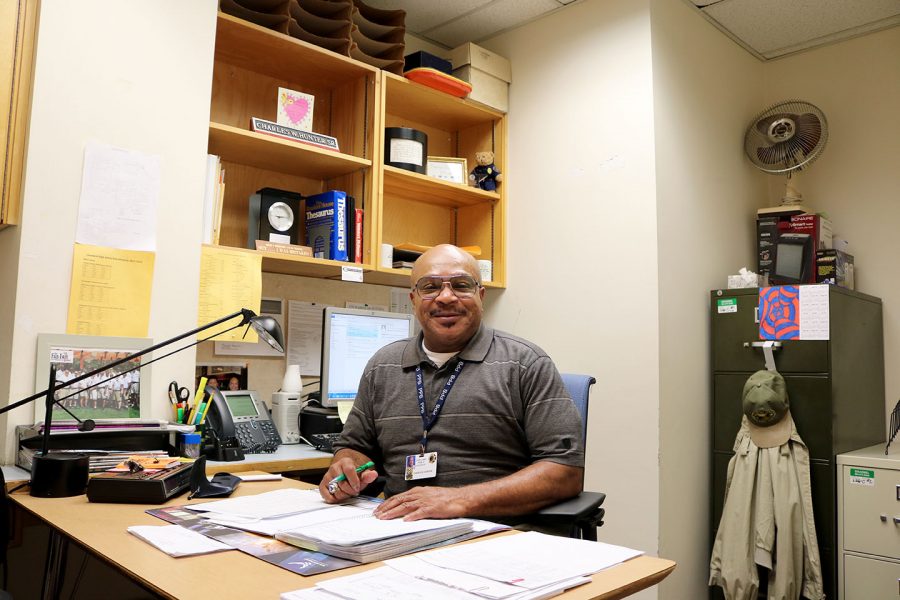

Darryl Miles, vice principal, described Restorative Justice as a strategy to help change frames of thought.

“It is called Restorative Justice because typically the people who have been having issues are underserved communities who have been marginalized or unjustly given punishments,” said Miles.

Charles Hunter is the Restorative Justice Coordinator at Cleveland. He explained that Restorative Justice stems from an old Indian philosophy of sitting in a circle and addressing positive and negative situations.

“When you have a situation where someone does the crime, then they do the time, then they do the crime, then they do the time, you have this revolving door,” Hunter said. “Restorative justice comes in and takes a different approach to it. You do the crime and then you stop for a moment and talk about it.” He described Restorative Justice as bringing “wholeness” to a broken situation.

Restorative justice is not simply for one-on-one conflicts; it can also be implemented with schools, communities, and cities.

Hodge noted that while it is much harder than current strategies of discipline—it is more expensive and takes more time, resources, energy, and resources from everyone involved—it has been seen to change lives.

Recently, a school in Philadelphia implemented an intense Restorative Justice program and practiced it throughout their school. In one year, rates of violent incidents dropped 90 percent.

When Hunter was dean of students at Grant, staff members gave 1,000 referrals to students. The year he instituted Restorative Justice, they cut the number of referrals to only 480, more than 50 percent of the original number.

“The point of Restorative Justice is to find the root of the problem and then try to solve that instead of solving what is bubbled up to the surface in a punitive way,” Hodge said.

Hodge explained that some factors that often affect students behavior are misdiagnosed mental illness, being born into a community that is systematically oppressed, and being in a low socioeconomic class.

“A lot of times, just having one conversation can make a positive impact,” said Hodge. “Instead of using fear tactics, intimidation, or some sort of coercive practice to keep students in line, it encourages educators to set up a system that allows students to do their best.”

To completely create a discipline of Restorative Justice, one needs to be trained, which is a process that lasts around three to four months. However, the message behind it can be implemented into any classroom as long as educators are informed about the meaning and purpose.

Recently, Resolution Northwest—the headquarters for the Restorative Justice program—led a session of Restorative Justice with Chinook, Stumptown, and Rhapsody academies. Hunter and two other professionals each went into a room, circled with students and confronted pressing issues. “We addressed the words ‘b**ch, n***er, gay, diversity etc.’”

“It was a strict protocol but it allowed for students to sit in a circle and air issues that they feel are impacting them or that they see are impacting others in a very open and nonthreatening environment,” said Lynne Allers, Modern World History and Epic Issues teacher.

After the successful discussion, Allers aims to have her classes participate in two more sessions of Restorative Justice. “It helps to change the dynamic of the classroom,” she said. “I would quantify it as academic learning in and of itself.”

Hunter hopes that Restorative Justice will continue to be implemented in the classroom, leading a non-punitive approach to discipline.

“I am pro-restorative justice because it doesn’t point fingers at who is wrong or right; it just resolves a situation and makes it whole for everybody that is involved,” Hunter said. “This to me is the greatest thing that has happened since the invention of education.”