The flaws in our current education system

May 10, 2016

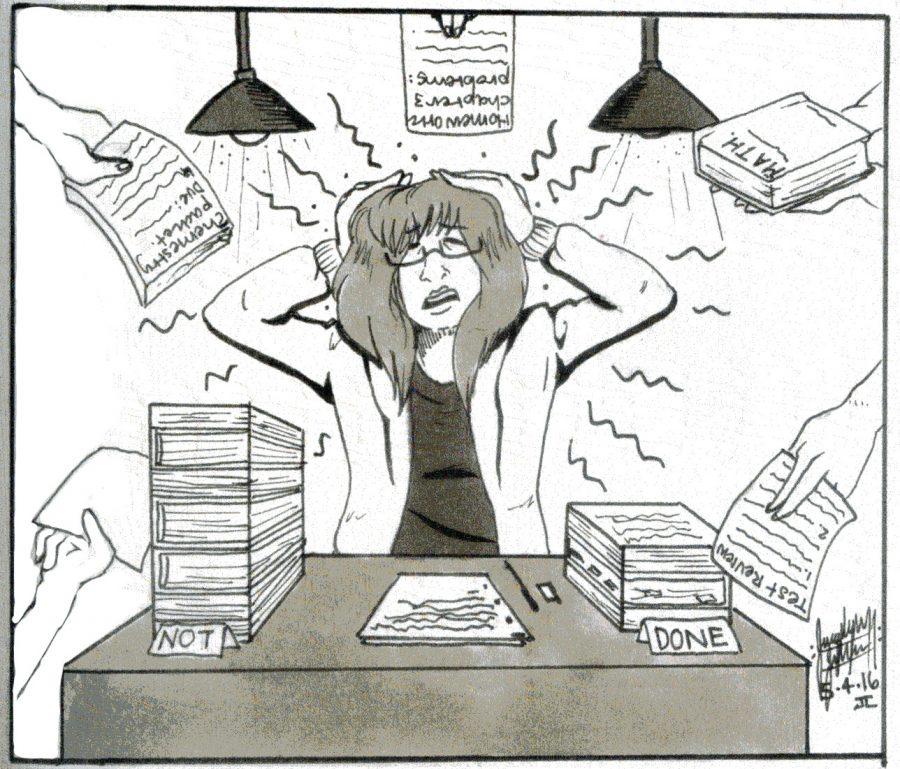

It is dead in the heart of the school year, and after eight months of studying incessantly, we are far past burned out. We’ve spent years facing the demands of greedy corporations and standardized tests. We’ve been robbed of our rest for countless nights on end, developing an acute sense for the silence of seclusion. We’ve killed thousands of hours of daylight, willing ourselves to believe that our day was better spent ignoring our loved ones for the sake of completing an assignment. And most of all, no matter how hard we cry for our voices to be heard, they are lost to the muffler of the monster: our education system.

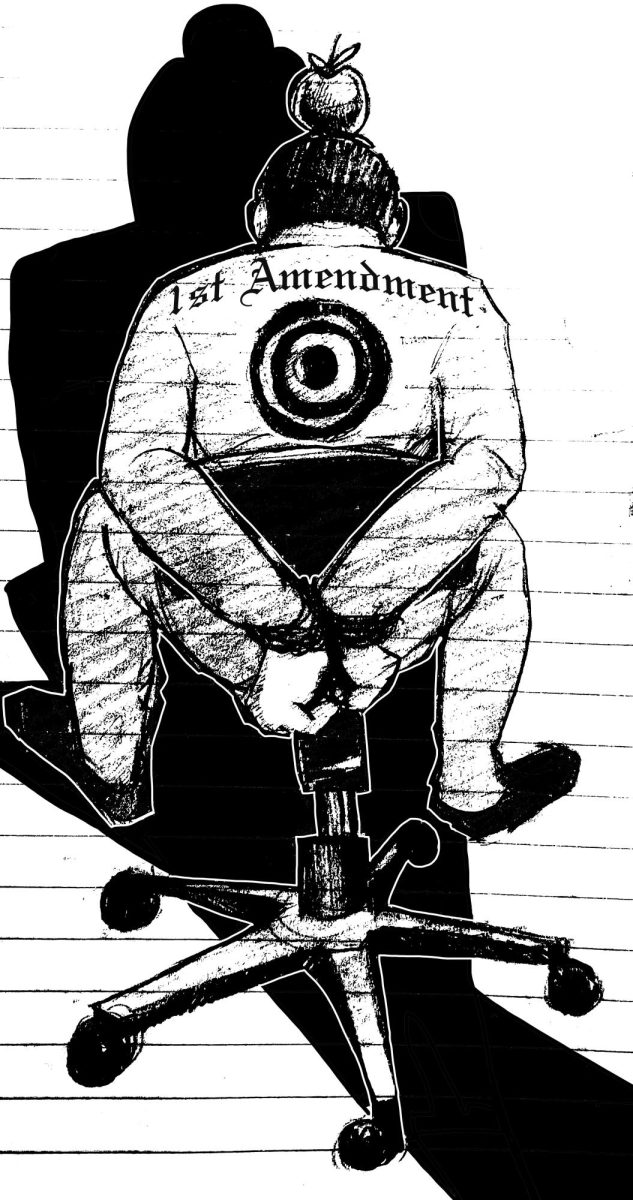

This is the reality for hundreds of thousands of students across the United States. On average, high school students are assigned as many as seven to 25 hours of homework weekly, and are subjected to nearly 115 different standardized tests by graduation day. The testing culture has bred a bloodthirst for competition, and education has become a game of who can best play the system. There is little emphasis on learning, and more focus on test prep and ratings. Most frighteningly, as students, we have no say in the content of the material we are learning, nor do we have a voice in the way that it is presented to us. School is no longer a temple for knowledge, it’s a numbers game.

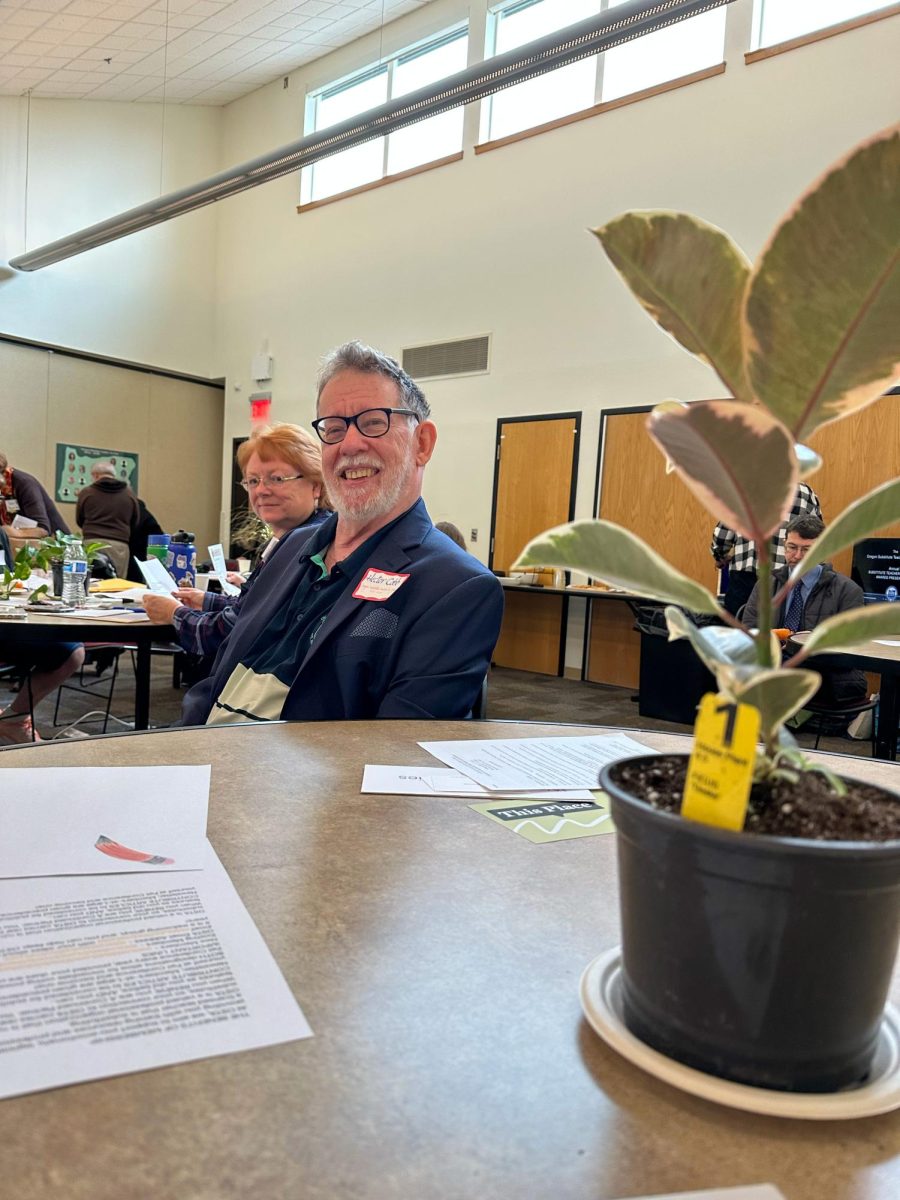

Fortunately, the conversation for improvement has been sparked. Cleveland teachers John Golden and Tim Graham have long been developing an outlet for discussion on these issues, appropriately dubbed, “The Homework Summit.” During the past month, Golden and Graham have taken account of nearly 700 surveys from students, teachers, and parents. Through this process, the two have garnered some frightening results.

On average, 14.5 percent of juniors and seniors stated that they had over eight hours of homework per week. The survey also found that 36.1 percent of students recorded that homework did nothing to help or hurt their grade. Even more shockingly, 54.8 percent of students reported that the homework did not help their learning, while 74.1 percent of teachers thought that the homework improved understanding. If three out of four teachers believe that the homework they assign is aiding a student’s learning, yet half of the student body is reporting that it doesn’t, there is something seriously wrong. These statistics illustrate a major disconnect between teachers and students.

Why is it that teachers assign so much homework and that students are so unreceptive to it? As to the former, some theories hypothesize that teachers feel a need to assign homework to appear rigorous or to balance out test scores and cushion grades. Others argue that repetition is key, and that without it, students cannot thoroughly understand concepts. And for some subjects, this has proved to be true. A 2011 study involving 25,000 eighth graders found that a little extra math homework improved test results by three percent. However, these findings did not apply to any other subject. Furthermore, any amount of math homework over 15 minutes was found to be ineffective. Of course, this study accounts only for eighth grade level math and does not include higher-level practices.

Even so, excessive amounts of homework have proved to take a negative toll on a student’s learning. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “After four hours of homework per week, the additional time invested in homework has a negligible impact on performance.” This, perhaps, is the reason why students find excessive homework to be so unbeneficial. Scientifically, it’s not helping.

Furthermore, having exorbitant amounts of homework takes away from other important elements for child development: rest, extracurriculars, and family time. A 2014 poll conducted by the National Sleep Foundation found that homework made it hard for four out of 10 students to get a good night’s sleep. Likewise, according to Vicki Abeles’ Beyond Measure: Rescuing an Overscheduled, Overtested, Underestimated Generation, sleeping is known to be one of the most efficient ways to retain information. More efficient, in fact, than homework. Additionally, sleep has proved to heighten test scores and to advance learning and comprehension. Moreover, excessive homework takes away from childhood. Instead of digging up worms in the backyard and playing hopscotch among friends, children are forced to stay inside and stare at a piece of paper. Since when is school the only outlet in which students can learn and grow? Children can learn some of their greatest lessons on a playground, and this element of growth cannot be discounted.

Moreover, for a system that prides itself on equality for students, the education industry in the U.S. certainly doesn’t account for the inherent disparity in student resources. “Homework exacerbates inequality between families,” said Abeles. “Our public education system strives toward equality—yet when it comes to homework, we expect all children to perform the same with vastly unequal resources.” Some students simply do not have the equipment at their disposal to complete assigned tasks, and some students do not have the time between family commitments and jobs to manage them.

If these students do not even have the resources to complete homework, how can they be expected to compete on tests nationwide with those more affluently disposed? This is just another flaw in the competitive nature of our school system. Rather than learning the material, our education system has begun to emphasize the over-importance of test scores. Ranking students amongst one another has become so essential to moneygrubbers like the College Board, that even the school system has adopted it. These scores are supposed to demonstrate a student’s ability for success in college, yet scores, grades, and GPA don’t account for quality of work or for accountability; they’re purely numbers. These numbers don’t mean anything toward what you know, they’re just another way to make students into statistics.

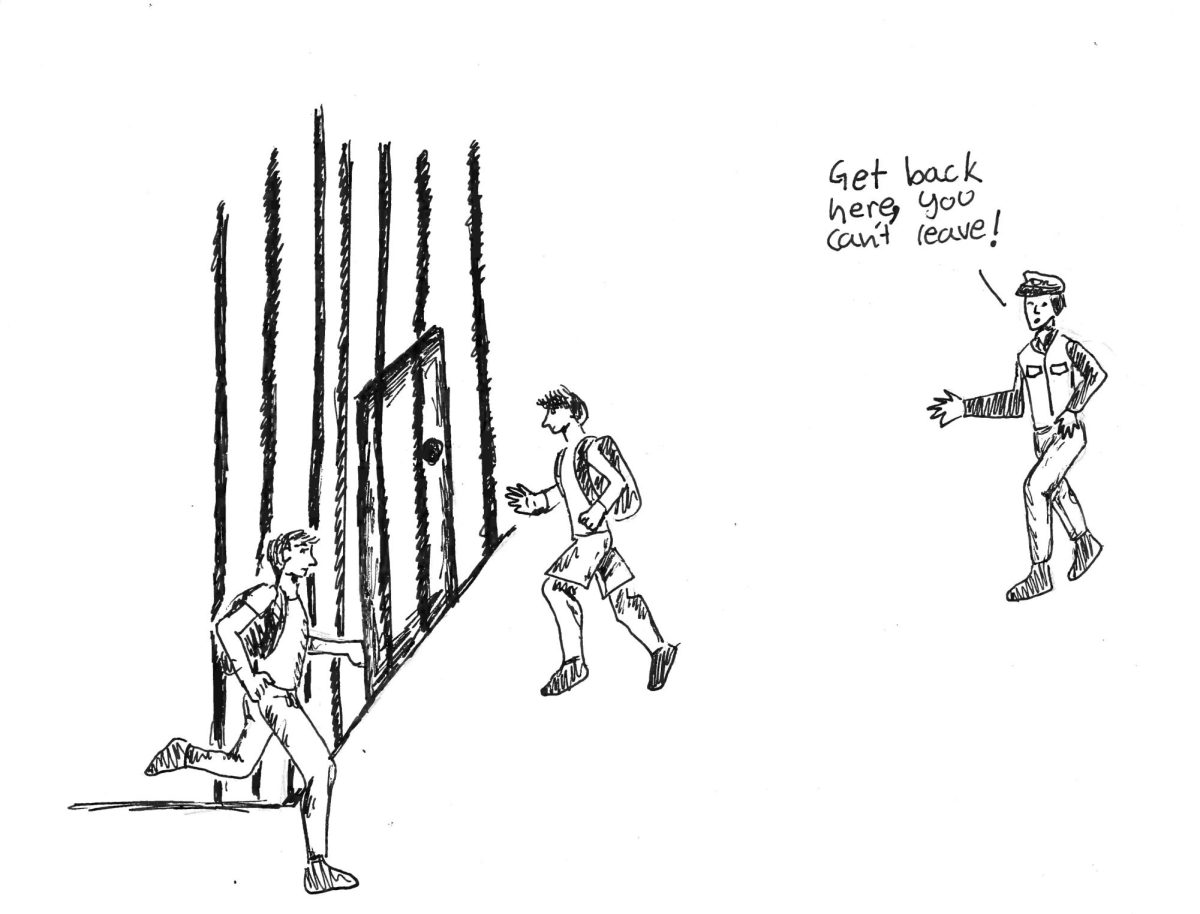

Ask any I.B. student, and he’ll tell you that while he has at least three to seven hours of work waiting for him at home, his class time goes to waste. It’s the Cleveland consensus—the classes that we are assigned the most work for accomplish the least during the school day. So what’s the point? We have exhausted students, mountains of homework, mindless classes, unequal resources, and over-emphasized test scores. We’ve recognized the issues, but the problems repeat themselves year after year. We’re not learning in the place we go to learn, and it’s a sad and unsettling reality. And yet, here we are, ready to do it all over again.

Earlier this year, I had a long-term substitute teacher who redefined the meaning of learning. For me, he reinstated the purpose of what education stands for and encouraged open discussion and thorough investigation. This is exactly what our school system needs to create a successful learning environment. Rather than doing work that ties us to desks, let’s explore the world around us. We need to rediscover our educational culture, the process of learning. We need to reclaim our education by taking the risk, because standardized tests and mountains of homework aren’t making us smarter, they are burning us out.