The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Ethics in Zoos

Clarion photo Jacquelyn Johnson

April 27, 2017

As a child, my life was deeply enriched by the Oregon Zoo. I have fond memories of seeing my favorite animals in action, chowing down on sweet treats, and of course, visiting the gift shop. It is unquestionable: the zoo profoundly cultured my love for animals.

As I grew older and became aware of the innate issues surrounding the act of keeping animals in captivity, my love for zoos faltered. I felt as though I had been fed a single-sided narrative in which all problems with zoos were exempt. However, upon doing research into the criticism of zoos, I still could not find a fair evaluation. In truth, neither zoo-critics nor zoo-lovers provide a fair testimony of the ethics of keeping animals in captivity. This is because both fail to recognize that in order to improve zoos, we must escape the narrative that all zoos are the same.

Accredited zoos serve many great purposes in society. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), zoos educate the public, develop technology that is used to track populations of animals living in the wild, raise money for conservation and protection programs, advance veterinary medicine, conduct scientific research, and develop animal handling techniques. Zoos are leading the charge towards saving endangered species in the wild and implementing technology to improve the lives of animals in captivity. Their contributions to the study of animals are invaluable; without zoos, it is very possible that the scientific community would not be as knowledgeable about animal behavior or as keenly aware of species extinction as it is today.

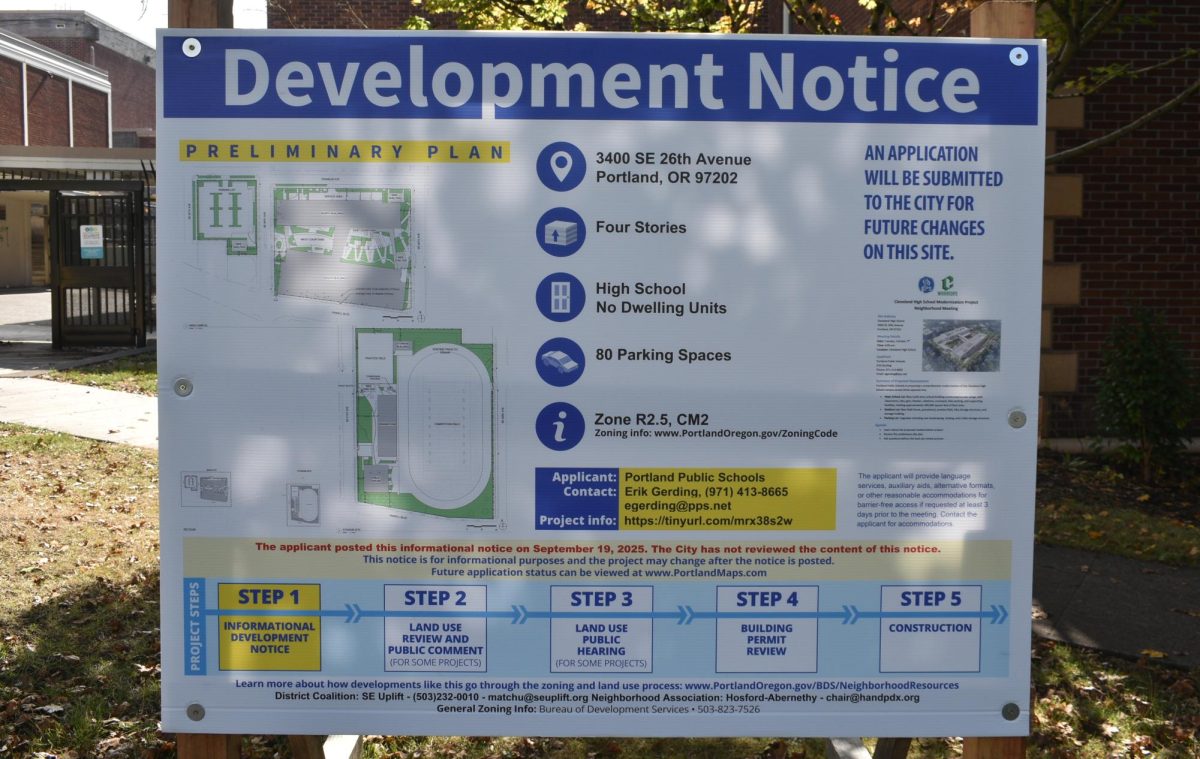

As of September 2016, less than three percent of zoos in the world were accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). Upon first inspection, this number appears startling. However, when one considers how grueling and extensive the process of accreditation is, the low percentage starts to make sense. To be accredited by AZA, each zoo must undergo extensive evaluations for animal management and care. This includes a comprehensive assessment of individual animal living environments, social groupings, health, nutrition, veterinary and education programs, involvement in conservation and research, zoo financial security, and zoo safety policies and procedures. Additionally, because AZA’s standards are constantly evolving, zoos must be reaccredited every five years. This extensive evaluation ascertains that animals living in accredited zoos are treated very well. This includes the animals living at the Oregon zoo, one of the only 232 accredited zoos out of the 10,000 across the world.

It is also important to note that many of the animals in zoos have been given a second chance at life. Wounded animals are often rescued from the wild and brought into captivity to be healed by trained medical professionals. If the animal has not become reliant on humans upon full restoration in health, zoos do their best to release the animal back into the wild.

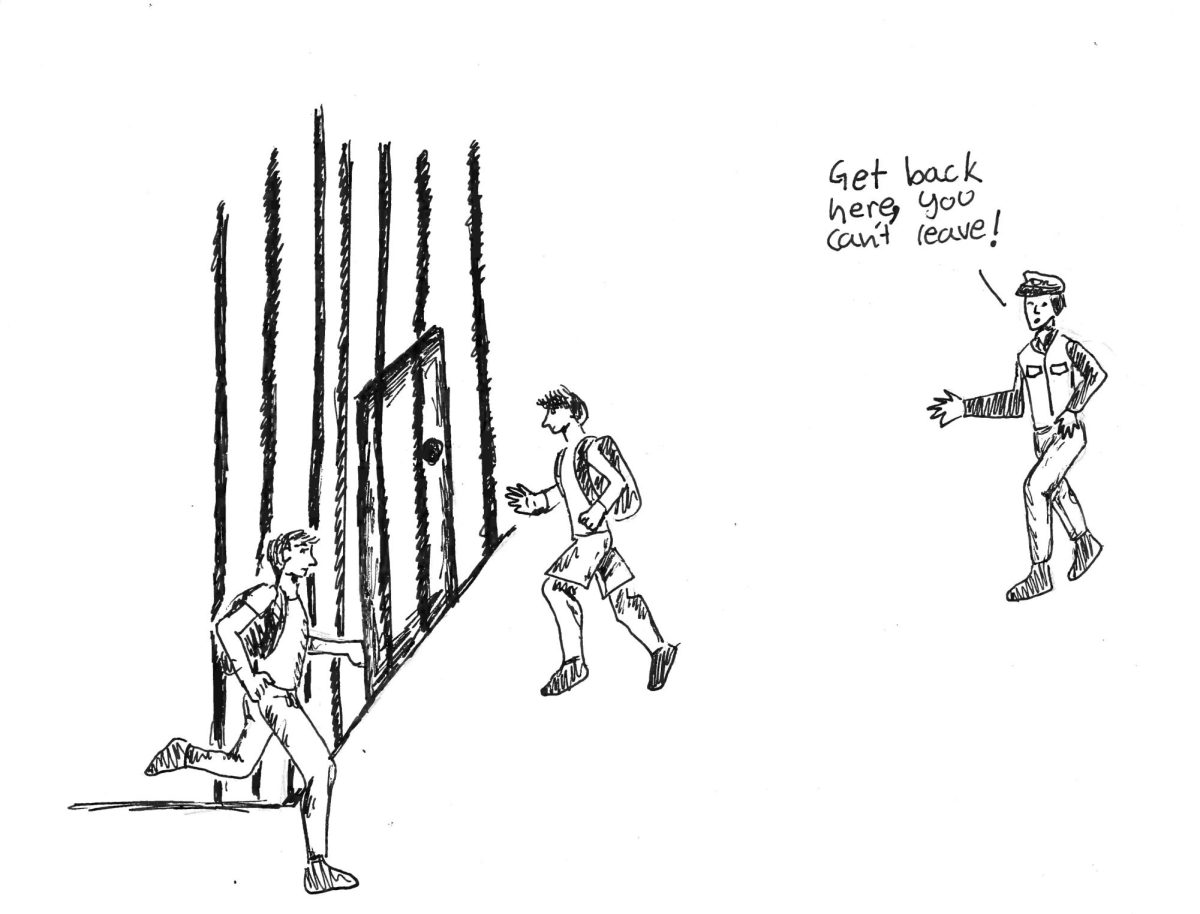

Even considering the benefits and contributions that zoos make to their animals and to society, one cannot ignore the fact that there is something innately wrong about trapping a living, sentient being in a cage. According to Detroit Zoological Society Executive Director Ron Kagan, animals are not happy if they live without choice and control in their environment. This is similar to human restlessness. Just like homosapiens, the rest of the animal kingdom needs to feel as if its individual animals are in control of their own lives.

Furthermore, animals have an intrinsic right to liberty. Animals are entitled to and deserving of fair treatment and equal opportunity at life. It is often assumed that humans are superior to other animals. In truth, there are many species that are fundamentally much more important to the health of the Earth than humans are. Instead of elevating these species and allowing them to carry out their roles in making the world spin, humans are destroying their habitats, trapping them in cages, and ruining their chances at life.

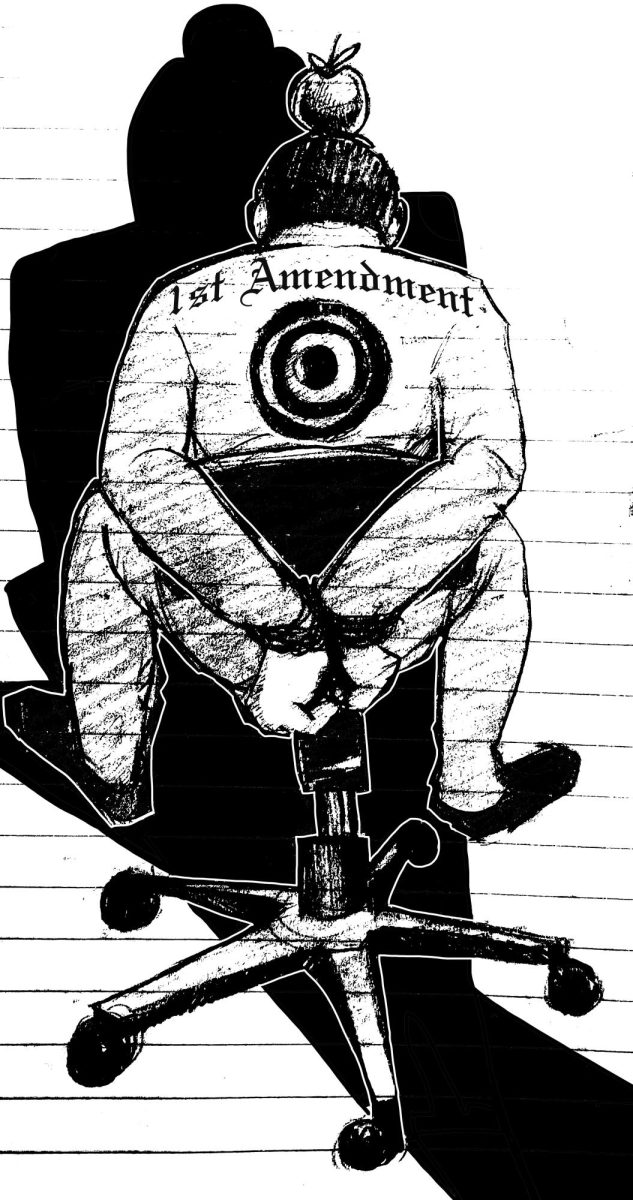

Additionally, many critics question whether zoos truly motivate consumers to make contributions towards conservation. “Zoos have painted themselves as saviors of the wild. I fear that this has instilled a false sense of security in the public mind,” said David Hancocks, a former zoo director. “Many people now believe they don’t have to worry about saving animals because zoos are doing the job.”

Zoos were founded for evil reasons—so that humans could gawk and throw peanuts at exotic animals—but they have evolved exponentially since first creation. Through advancements in technology and comprehension of animal behavior, zoos have made extensive efforts to create habitats that closely mimic those animals would experience in the wild. Zoos have increased space for animals to roam, have incorporated natural sounds in habitats, and have carefully designed enclosures to introduce elements of living in the wild. Slowly, zoos are evolving.

Depending on your values, zoos can be perceived in different ways, and it is an individual consumer’s choice in deciding whether or not to support them. However, before coming upon a conclusion, it is important to distinguish that all zoos are different. It is easy to remain ignorant to the issues that zoos exhibit or to recycle the narrative that all zoos are animal prisons. However, it takes strength and dedication towards the wellbeing of animals to diverge from these single-stories and instead evaluate zoos based on individual merit rather than decided generalizations. It is imperative that consumers ask hard-hitting questions and educate themselves on individual zoos before deciding whether or not to support them.

Put your money where your mouth is. The welfare of animals in captivity is dependent on it.