ALMOST ARMAGEDDON

Human incompetence in nuclear bomb facilities

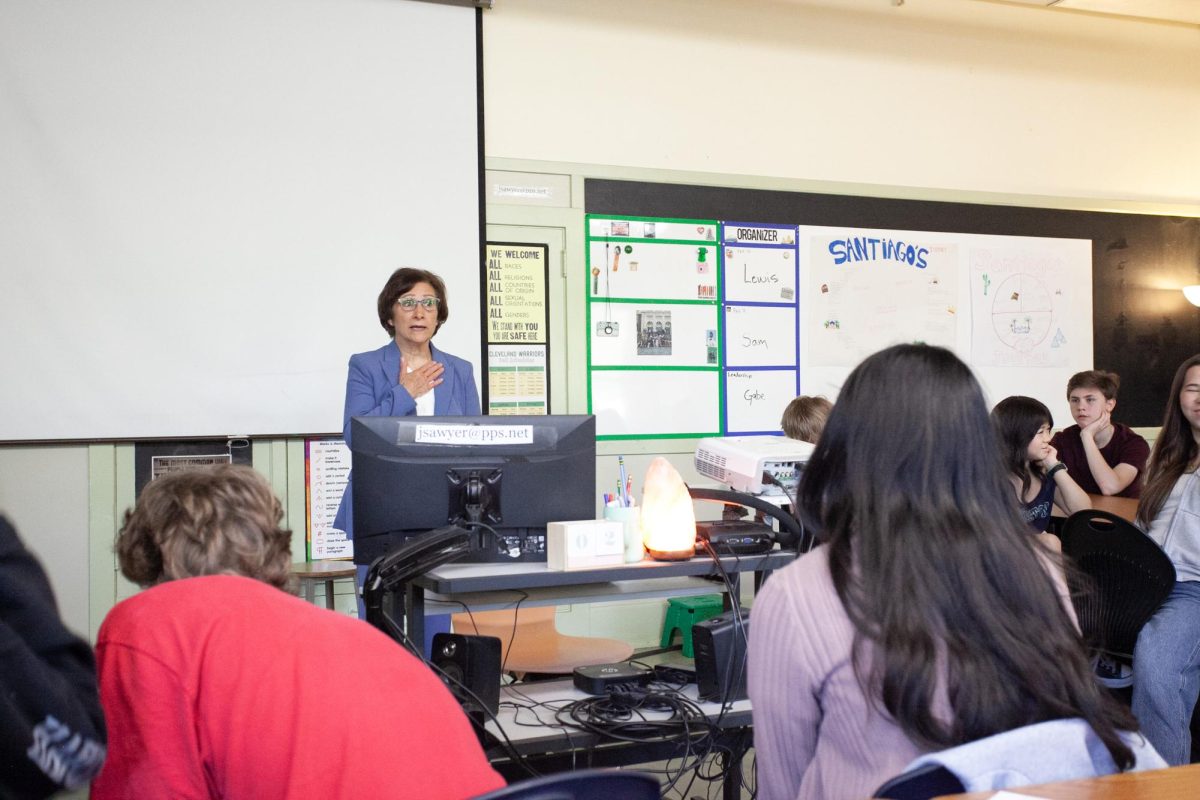

February 27, 2018

BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.

So ended the emergency alert issued to over 1.4 million Hawaiians on the morning of Saturday, Jan. 13. Almost immediately, panic ensued. The heart-stopping message caused countless recipients to fear for their lives, assuming a nuclear attack at a time of heightened tension with North Korea. Citizens made desperate calls to their loved ones, believing they had only minutes to say goodbye. Others clustered indoors, abandoning their cars on the streets and huddling behind counters or under tables among throngs of strangers.

Little did any of them know they had nothing to fear ー there was no missile.

The false alarm was caused by just one employee at the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, who simply pushed the wrong button. In the midst of a drill, this employee selected “Missile Alert” when they were supposed to choose “Test Missile Alert.” The power to throw all of Hawaii into a state of fear and confusion for 38 long minutes was held in human hands ー hands that made a tiny, even trivial mistake in the heat of the moment.

Luckily, this employee didn’t have access to a “Fire Missile” button; if they had, we can only imagine what could have happened. However, the Hawaii false alarm is a perfect example of why humans are exactly the wrong creatures to be handling nuclear weapons. We’re inherently messy, imprecise beings, and we defect easily ー from physical slip-ups to our psychological natures, almost everything about us is ill-suited to be in potentially explosive situations involving nuclear bombs. Even though we stand behind the controls, the power to remove this ever-present threat of human error is absolutely out of our hands.

Take the story of Dave Powell, a young missile technician who almost wiped the entire state of Arkansas off the face of the earth in September 1980.

It all happened deep underground the town of Damascus, Arkansas, in the stronghold of the Titan II Missile. This intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) remains the most powerful nuclear warhead ever built by the United States ー said to be 600 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. Powell was in the midst of a routine check-up on the missile when an eight-pound socket from his socket wrench slipped from his fingers, bouncing to the edge of the platform he was working off of and falling out of sight. The socket plummeted 70 feet down, striking the side of the nuclear missile and piercing its thick metal wall. Spraying out of the wound was an uncontrollable flow of highly pressurized rocket fuel, seeping rapidly into the chamber below.

If you’re familiar with the way nuclear missiles work, you’d know that this wasn’t just any leak. The kind of fuel used in ICBMs at the time was extremely combustible and very sensitive, reacting violently to a wide range of substances, from paper to rust. And the worst part? Rocket fuel wasn’t the only highly volatile liquid found in the Titan II, there was another substance called oxidizer also stored inside the missile. If these two liquids were to meet at any point other than in the motor, they would instantly combust, creating a massive fire and potentially destroying the missile silo. To the horror of the U.S Air Force, that’s exactly what happened at around 3 a.m the following morning. The staff of the Titan II, who had only just evacuated the facility, witnessed the fiery eruption bloom from the earth. Huge chunks of metal and concrete were thrown into the air, some as big as cars or even school buses.

By pure chance, the nuclear warhead fitted to the Titan II had not detonated as a result of the fuel explosion. Miraculously, it had remained intact, and was spewed from the ruins of the facility along with the rest of the debris. Hours later, it was found a quarter of a mile away, unharmed and lying innocently in a ditch. Its detonation would have caused a massive cloud of radioactive fallout to envelop much of the southeast U.S ー in other words, game over for the millions of Americans living within its range.

If there’s one thing the Titan II fiasco proves, it’s that human error is eventually inevitable, no matter the amount of training employees receive. Just look at what happened to Dave Powell, who simply dropped a wrench and inadvertently came within an inch of causing a nuclear disaster. We imagine that powerful nuclear bombs like the Titan II are untouchable, surrounded by armor and locked away until the day of their detonation. In reality, they require constant maintenance, and must be cared for, repaired, checked, and rechecked by people like Powell every hour of every day. The consequences of a small blunder on their part can be potentially deadly.

But while physical errors like dropping a wrench or pushing the wrong button can certainly come with a hefty price, there’s another flaw that makes humans ridiculously ill-fitted to interact with these civilization-ending weapons: our emotions. Humans lack the ability to be constantly calm, cool and collected in volatile situations. Once we’re on edge, we’re more likely to become agitated and convince ourselves of the worst.

This came into play for a team of North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) members during the Suez crisis of the Cold War. On the night of Nov. 5, 1956, this team received a series of high-risk, simultaneous alerts that almost provoked a misguided nuclear strike against the Soviet Union.

Alleged events included a British bomber shot down in Syria, unexpected maneuvers by a large Soviet fleet through Turkey, 100 Soviet MiG-15 fighter planes over Syria, and unidentified aircraft flying above Turkey. All of these events seemed to point to a Soviet offensive. The U.S and the Soviet Union weren’t exactly allies at the time, and the Soviets had a recent history of making reckless nuclear threats to their enemies. With all this in mind, the team informed U.S general Goodpaster of the series of high-risk alerts, telling him they were all in imminent danger. Goodpaster reportedly believed this justified an immediate nuclear retaliation against the Soviet Union.

Minutes later, Goodpaster was notified that each of these reports was, in fact, the result of misinterpretation, exaggeration, assumption, or sheer coincidence. After experiencing mechanical problems, the British bomber had been forced to land in Syria to fix his plane. The Soviet fleet over Turkey was simply engaged in routine exercises, while the 100 Soviet fighter planes over Syria were a part of the air force escort for the then president of Syria. Last, but certainly not least, the unidentified aircraft flying above Turkey was later attributed to an unusually large wedge of swans.

This story is an excellent example of how poorly humans judge risk. We have two conflicting sections of our brain that tell us to do very different things in response to danger. The first is the Neocortex, an evolutionarily young part of the brain in charge of advanced analysis. The Neocortex is intelligent, but it’s also very slow compared to the other part of the brain that deals with risk ー the Amygdala. This primitive section of the brain is all about the fight or flight response, and is primarily concerned with survival. It’s much faster at forming conclusions than the Neocortex, meaning it can have a far bigger influence when we feel truly endangered. All this means that humans are hardwired to jump to conclusions when computing how risky a situation is, including factoring in past emotions and experiences in the process.

The problem is, working in a nuclear facility requires a much more sophisticated analysis of risk, because the stakes are so enormously high. When there are thousands of lives hanging in the balance, it’s more important than ever to judge the situation clearly and thoughtfully, then come up with a logical course of action in response. That’s exactly the opposite of what the team of NORAD members did, allowing fear and primitive survival instincts to take control.

In this era of heightened tension and advanced technology, It’s more important than ever for us to recognize how ill-equipped humans are to be interacting with nuclear weapons. The relevance of this topic has not disappeared over the years, regardless of what we’d like to believe. In fact, there’s a nuclear accident just waiting to happen in the U.S today ー and he’s currently sitting in the oval office. In his first year as president, Donald Trump has steered the country into dangerous waters regarding nuclear war, namely by provoking North Korean leader Kim Jong Un via Twitter. In one tweet, Trump said, “ー Kim Jong Un just stated that the ‘Nuclear Button is on his desk at all times.’ Will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform him that I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!” It seems like Trump is attempting to inflate his already larger-than-life ego by making nuclear warfare into a competition. While it’s easy to laugh this kind of thing off, it’s misleading to compare Trump to a whiny little kid picking fights on the playground. After all, he does hold real power. Trump is playing a very dangerous game, treating the potentially devastating, military-grade weapons that are at his disposal like toys.

So what does it all boil down to? We’re not as safe as we might think. Combine man’s unpredictable tendencies, primitive survival instincts, and egotistical nature, and you have a recipe for nuclear disaster. And remember, we don’t really know what will happen if full-scale nuclear war breaks out. Long-term environmental, agricultural, and health-related implications would have to be factored into the equation, as well as the immediate loss of human life. Weapons with the power to end entire civilizations are way more trouble than they’re worth, especially when they’re handled by humans. Will we put a stop to these perils? Or will we continue to live life knowing that one tiny slip up at the hands of a human has the potential to cause a cataclysmic World War III?