Learning to Hear Cleveland’s Deaf Community

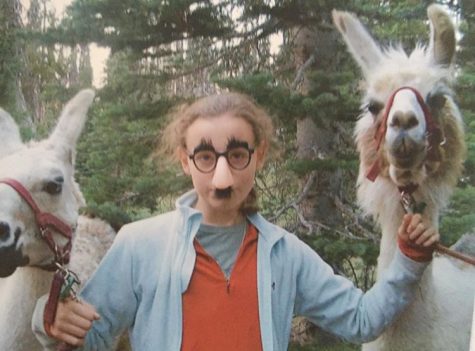

(Left to right) Melissa Carrasco-Casillas, Jessica Pineda, and Jaden Lee sitting together in their Transitional Skills class. Mckenzie Potter-Moen photo.

February 28, 2018

“What hearing people can do is just try. Acknowledge that they’re there, and have eye contact, and use body language, gesturing, using an interpreter, writing, just making that effort to try,” Sara Outcalt, teacher of the deaf at Cleveland High School, currently home to three students who are deaf.

Cleveland is currently the only Portland Public Schools (PPS) high school with a designated program for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. The middle school program is at Mt. Tabor, and the elementary program is at Creston.

Cleveland currently has three full-time deaf students, sophomore Melissa Carrasco-Casillas, junior Jaden Lee, and senior Jessica Pineda. They have a class designated to deaf education called Transitional Skills with Sara Outcalt, teacher of the deaf.

“In this class, we read a lot, we learn a lot, we practice writing, how to communicate, especially with hearing people, we take field trips for practicing, we learn names of things. It’s a lot of helping with communication and clear understanding,” said Jaden.

Cleveland also has two interpreters, KC Black and Dan Campbell, who attend mainstream classes with the deaf students.

“[The interpreters] will summarize and explain and then it’ll help me understand, and then I can become independent,” said Jaden. “If it’s a tough sentence, then the interpreters work with me. It’s really important to try to understand the English through the interpreters and through Sara helping us learn how to communicate.”

Communication was a shared struggle among the three of them in mainstream classes. “Same thing with that English stuff, it’s such a struggle and frustrating,” said Melissa. “I don’t understand a whole lot of English yet. My English class is with Ms. Goldbloom, and KC’s my interpreter for that class and helps me understand more clearly. Remember English itself and sign language itself are different languages.”

The interpreters sometimes stand next to the teacher to help comprehension with the deaf student. They emphasized that they’re not in the classrooms to be heard as themselves, but solely to be the voice of the deaf student. They also discussed the nuances of talking to someone through an interpreter.

“Hearing culture considers it polite to look at who is talking, but remember that although you are hearing my voice, you are communicating with the Deaf person I am interpreting for,” said Black. “Always direct your conversation to them. Interpreters will place themselves where the Deaf person can see the person they are talking to AND the interpreter. Another important thing to remember is that interpreting is a process that takes time. Interpreters have to listen, change languages, convey the message, receive an answer, change languages again, convey the message in the other language. This causes a ‘lag’ time. Please be patient. The Deaf person is not ignoring you.”

With the help of interpreters, the opportunities for deaf students regarding school involvement have increased as well. Melissa and Jessica joined the Cleveland cheer team this year. The interpreters switch off, coming to every practice and game to help the communication between them and their hearing teammates. “With cheerleading, they’re all hearing and I won’t understand them and I have to have the interpreter next to me and explain to my friends, ‘Hey, this is how you can help me.’ We have stunts that we do in cheerleading and different cheers and everything,” said Melissa.

Other PPS high schools are making efforts to engage and educate in Sign Language and Deaf Culture. Lincoln High School offers a class on American Sign Language, though there are currently no students who are deaf attending. Similar to Cleveland, Wilson High School has an ASL club. The Wilson website writes that the club’s mission is “that students can continue to immerse themselves into the Deaf Community. This club is here to build new friendships and strengthen the relationship between language and student.” The Wilson principal stated that it was a “popular” option among students.

Cleveland began its own ASL club earlier this year, led by senior Will Tsai, that meets on Mondays during lunch in Gaye Chapman’s room, 384. It’s open to anyone and teaches about Deaf Culture and basic sign language skills. Jaden, Melissa, and Jessica often attend with an interpreter to help teach fellow students and simply communicate with more people in sign language.

“In school you’re taught languages, like you have the choice to learn a language, but you’re not really given the option to learn [ASL], even though there are people in our school who communicate through that, who, if you want to know them or interact with them that’s a language you need to understand, or you need to speak through an interpreter,” said senior Ariel Harmon. “I think it would be good to offer it as a language.”

Deaf and hard of hearing is considered a “low incidence disability” in terms of special education in the district, but PPS still provides many resources for deaf students. Resources for deaf and hard of hearing students in PPS primarily come from the Columbia Regional Program (CRP), which is a program that helps provide funding and services to special education in schools throughout Oregon. It’s responsible for setting budgets for school districts, and is also a provider for equipment such as hearing aids.

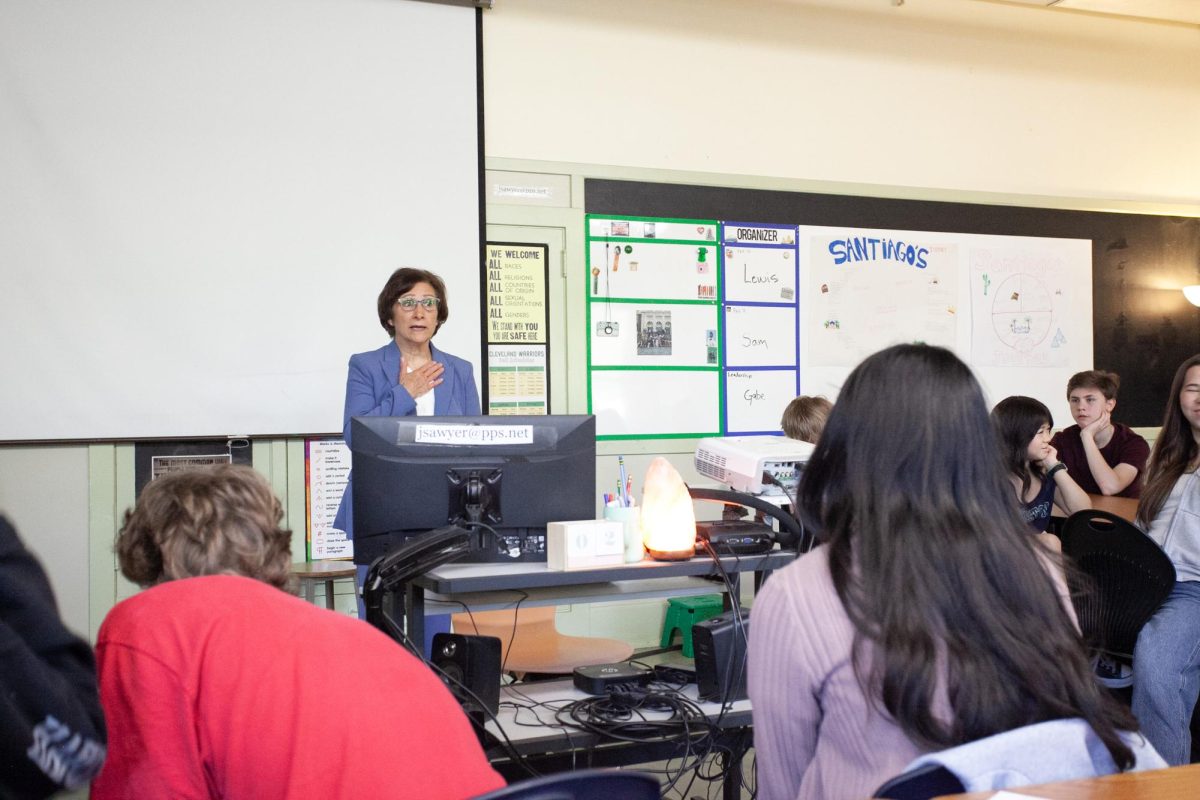

“We as a district, PPS, have agreed to help fund that, so those kinds of systems we’ll help pay for, and make sure the child has access to all of that in the classroom environment,” said Robert Cantwell, director of special education for Portland Public Schools.

While sign language is considered the commonplace form of communication for people who are deaf or hard of hearing, some people advocate for alternative forms of communication. Tucker Maxon is a private school for deaf, hearing impaired, and hearing students ages infant to 5th grade, located in southeast Portland. They don’t teach or use sign language at all, but rather teach the deaf students how to speak English out loud.

“Our mission has always been to teach deaf and hard of hearing children to speak versus sign,” said Tucker Maxon principal Linda Goodwin. “Sign is a beautiful language, and it’s a great asset for anyone to be able to do, but most people don’t know how, and so it’s limiting in that respect. As science and technology have developed over 70 years, the ability to give hearing impaired or deaf people technology that will help them hear has increased so much so it’s been more successful and easier.”

Every deaf or hard of hearing student who attends Tucker Maxon is equipped with hearing aids or a cochlear implant, which is a surgically implanted device to give people who are deaf or with severe hearing loss a sense of sound. The students work individually with speech pathologists to improve their speaking abilities, but most of the time they are in classes with the rest of the students.

“We try to teach our kids, by the time they’re in fifth grade, how to talk about their hearing impairments so they feel comfortable. We try and help the kids feel so comfortable that [they’ll come up to you.] They’ll talk about it as a matter of fact, so just being aware that they’re just like you except they can’t hear.”

The school also only teaches up to fifth grade, but Goodwin emphasized that the school’s main focus is to give children the tools to succeed anywhere they go. Some students may only spend a couple of years at Tucker Maxon before going to public school, and when they graduate they are prepared for middle school and high school.

“Many of our students go to Cleveland because Cleveland has that classroom [with] a teacher of the deaf who’s there and helps them manage their equipment. I’ve had students go there and they’ve had great experiences,” said Goodwin.

Speaking and sign are two different approaches to deaf communication and education. “Recognize there’s value to both perspectives,” said Cantwell. “Yes we have to navigate the larger world, but it’s ok to have a smaller microcosm of your own ancestry, your own cultural identity, or your own linguistic diversity that you might have in your own families. Let’s get kids what they need as they show it. [If they have] an affinity or an aptitude for learning better through visual and sign language, we should foster that and strengthen that rather than force something different on them, and vice versa; for kids that have cochlear implants [and prefer verbal communication], I think we should foster that and strengthen that, because that will serve them well in terms of having skills and tools for whatever they do later in life.”

Communication with any person, hearing or not, can be a challenge, but the most important thing a person can do is try.

“With hearing people I think it is a struggle, they’re not sure, ‘You’re deaf, I’m hearing,’ don’t say can’t. We can work it out, we can text, we can write, we can sign, and through that process it’ll improve. The struggle will get better, it’ll keep improving,” said Jaden. “Like at lunchtime, when we’re just chatting and hanging out, that’s kind of when I teach kids that I hang out with sign language. Don’t hang back, that won’t work, so feel comfortable, come, get involved, and we’ll get involved with you.”