One of Our Planet’s Present Problems: Pieces of Plastic

April 24, 2018

On Feb. 3, a Cuvier’s beaked whale was found stranded in the shallow waters off the coast of Sotra, a small Norwegian island. This already came as a surprise because these whales aren’t normally found near Norway, only ranging as far north as Scotland in the eastern part of the Atlantic Ocean. However, wardens were even more startled by the poor condition it was in. The whale appeared emaciated and had very little blubber left, which caused it to be put down when it became clear it wasn’t going to live for much longer. Something was definitely off, and the discovery of the cause doubled as the greatest shock of the whole incident. When scientists examined the whale’s stomach, they found more than 30 plastic bags and waste, all of which had labels in Danish and English, meaning the whale probably ingested most of the plastic further south. The debris most likely clogged up the whale’s intestines, causing severe pain and a slow and torturous death due to malnutrition.

Less than a month later, on Feb. 27, a 33-foot sperm whale washed up on a beach in Cabo de Palos in southern Spain. Like the Cuvier’s beaked whale in Norway, it too looked unusually thin. The contents in its stomach and intestines told an even grimmer story. In addition to plastic bags, scientists discovered ropes, fish netting, and a plastic water container inside the whale, totalling 64 pounds. According to officials, the whale died from peritonitis, an abdominal infection. Because the whale was unable to digest the overwhelming amount of plastic in its belly, its digestive system burst open. The sperm whale is an endangered species, which is not an accident: there is simply too much plastic in the world’s oceans.

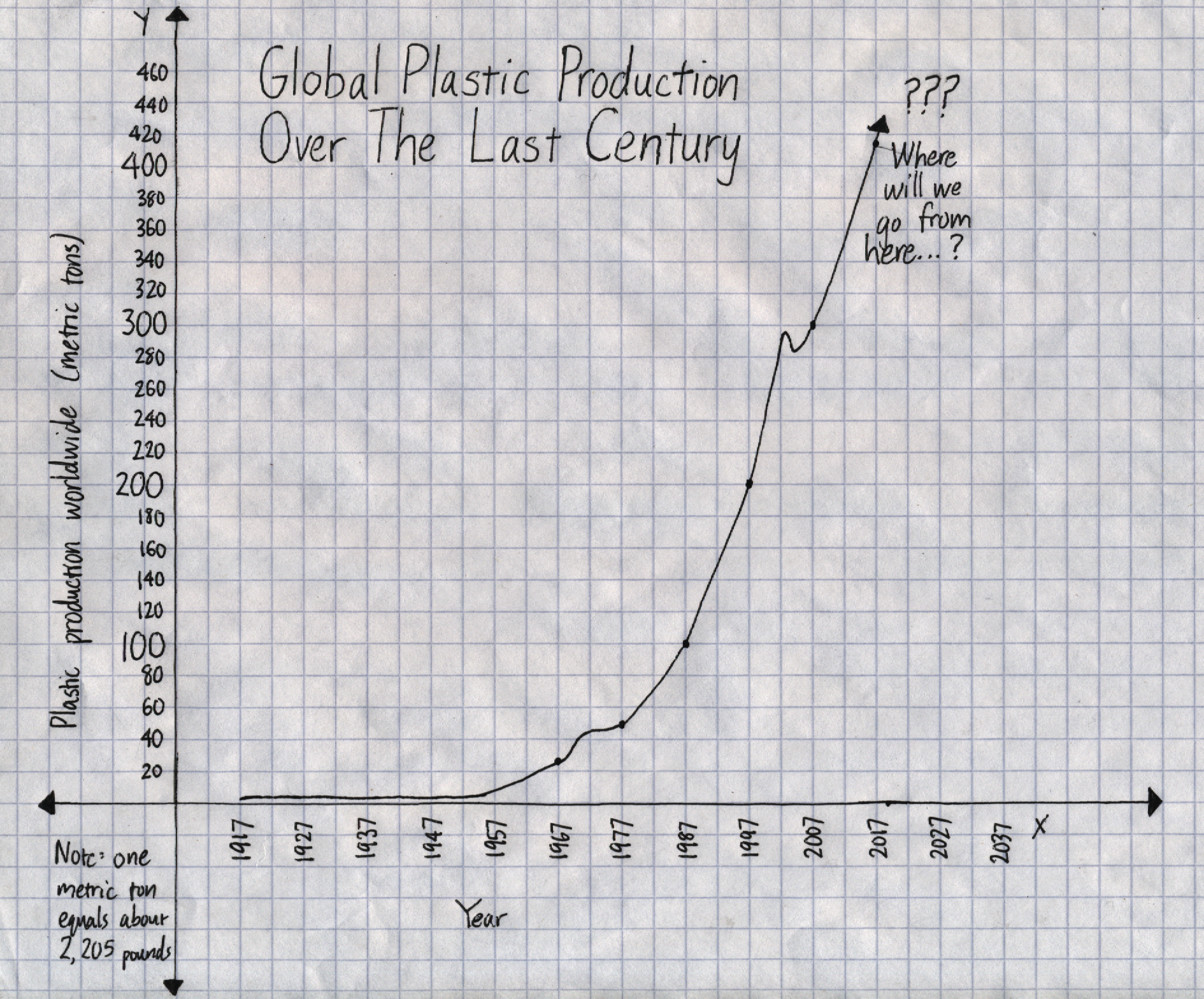

The global plastic problem isn’t a new phenomenon by any means, but the issue is that it hasn’t been thoroughly investigated until recently. Reports of plastic pollution in the world’s oceans first appeared in scientific papers in the early 1970s, but it wasn’t until 2010, nearly 40 years later, that a serious effort was put into estimating just how much plastic was finding its way into the marine ecosystem. Scientists discovered that in that year alone, approximately eight million metric tons of plastic (one metric ton is equal to 2,205 pounds) had entered the ocean, coming directly from people living within 30 miles of coastlines. To get an idea of how much this is, you can do the math (and eight million times 2,205 is a big number), or you can imagine it like this: eight million metric tons of plastic is equivalent to putting five grocery bags full of plastic on every foot of coastline in every country in the world. According a report by the World Economic Forum in 2016, the rate found six years prior is basically a garbage truck’s worth of waste pouring into the ocean every minute. If current trends continue, the rate will be two trucks per minute in 2030 and four trucks per minute in 2050. By that point, the amount of plastic in the ocean will outweigh the amount of fish.

Unfortunately for us, current trends have continued. Global production of plastic resin, which is used to make wrappers, beverage bottles, and plastic bags, increased to 299 million tons in 2013. That is a 647 percent increase from figures recorded in 1975. This increase hasn’t boded well for marine animals, as plastics have made their way into the guts of an estimated 86 percent of turtle species, 43 percent of seabird species, and 44 percent of marine mammals. In early 2008, two sperm whales were found dead on beaches in northern California, their deaths caused by ingestion of debris. The first, a 37-foot male, had 59 pieces of 44 different types of nets in its stomach, weighing nearly 49 pounds in all. Additional line pieces and bags brought the amount of ingested rubbish up to 53 pounds. The belly of the other sperm whale, a male measuring 51 feet, contained 105 pieces from 96 different nets, totalling 126 pounds. Line pieces and bags increased the weight to 162 pounds. First of all, the sheer quantity of waste in the whales’ stomachs is frightening, but equally important is the variety of waste that they ingested. It means that there are more than just plastic bags being dumped in the ocean, which will make getting to the root of this issue (and then solving it) more difficult. There is also the possibility of all these pieces of garbage accumulating in one place, creating a hazardous zone. And sure enough, in the Pacific Ocean, they have.

The world’s largest collection of ocean debris lies in a region between California and Hawaii, known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Covering an area around four times the size of California, it is made up of an estimated 1.8 trillion floating pieces of trash, like bottles, fishing nets, and plastic nets. Eight percent is made up of small particles of microplastics which can be easily ingested by marine animals who live within the zone. Sea turtles caught near the patch had eaten so much plastic that it made up as much as three-fourths of their diets. Scientists say the patch is growing exponentially, which, needless to say, is a really bad sign considering the patch already contains 87,000 tons of waste. In 2015, scientists measured the composition of the waste in the late summer, and although they discovered glass, rubber, and wood, 99.9% of the content they retrieved was plastic.

To the naked eye, the ocean may seem as blue and endless as ever. And it is. But that is precisely the reason why the copious amounts of plastic in the sea weren’t known for so long. It doesn’t seem like the oceans are teeming with debris, but that’s because only three percent (270,066 tons out of an estimated eight million) has been found floating on the surface. Just like with climate change, you don’t need to see a problem to know that it exists and is legitimately dangerous. I don’t want to wake up one day to discover that plastic has surpassed the world’s fish population. So be careful what you use. You don’t know where it might end up.