Police in Schools Do Not Make Them Safer

January 15, 2019

On Dec. 11, the Portland Public Schools Board agreed to pay over $1.2 million a year for nine full-time School Resource Officers (SROs) to continue being stationed in high schools. Until this decision, the Portland Police Bureau has provided SROs in schools for three days a week at no cost to PPS. District officials framed the decision as formalizing a practice that already exists, and argued that the district shouldering some of the cost would help the PPB, which is on a tight budget.

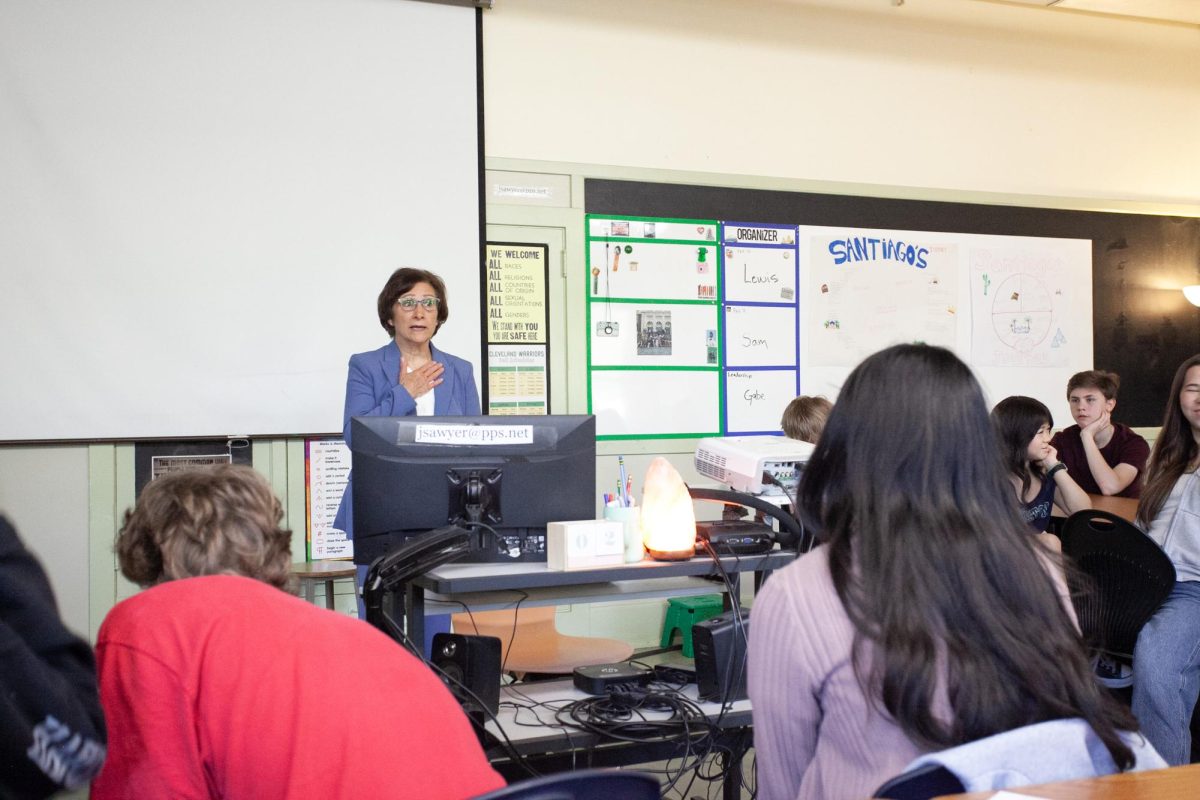

The board attempted to hold listening sessions for students and other community members, but the ACLU of Oregon say they received complaints that students were not contacted until very late in the decision-making process. They also allege that the listening sessions had heavy police presence, and that some were held during the school day, making them inaccessible for students.

Public policy decisions have paved the way for police in schools to be commonplace. But research shows that they do not actually make schools any safer. In fact, a police presence can actually be harmful to students.

The first account of a police officer being assigned to a school took place in Flint, Michigan, in the late 1950s. The number of police officers in schools gradually rose until 1990, when public outcry regarding a perceived increase in juvenile crime sent the amount of police in schools skyrocketing. In 1970, 1% of school administrators reported a law enforcement presence at their school. By 1997, 22% reported a presence, and by 2008, 40% of school administrators reported a presence.

Much of the need for SROs was created by federal policies that attempted to quell the public’s fears that youth were becoming more violent, and were carrying over problems that plagued their communities to their schools. Concerns about gun violence and school shootings led to the 1994 Gun Free Act, which allowed schools to have a zero tolerance policy regarding weapons on school grounds. Many states and school districts extended this zero tolerance policy to include drugs and alcohol. By replacing the somewhat arbitrary nature of school policies with mandatory disciplinary action, schools created a need for law enforcement officers within them.

In 1994, a federal program known as COPS (Community Oriented Policing Services) was established through a provision of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. The program allocated copious amounts of funding for law enforcement in schools. In 1999, COPS created the COPS in Schools initiative (CIS), which awarded over $750 million for the hiring of over 6,500 SROs. In total, CIS funded 13,000 SROs.

Statistically, a classroom is one of the safest places a child can be from violent crime. In fact, violent crime rates in schools are so low that there isn’t even really a sample to draw from when trying to compare violent incidents in schools with SROs and without SROs.

However, there is evidence that SROs lead to the criminalization of normal childhood behaviors. In the 2013-2014 school year, schools reported over 223,000 cases to law enforcement. A 2009 study by the Journal of Criminal Justice found that the most common charge by SROs is disorderly conduct. Having an SRO at a school increased the rate of arrest for this charge by over 100 percent, even when the economic status of the school was controlled for. This raises some questions, because disorderly conduct is something that is highly situational and subjective. “Compared to more objective situations like finding a youth in possession of a knife or narcotics, the decision to interpret disruptive behavior as criminal is done at the officer’s discretion,” said the authors of the study.

At the listening sessions regarding this board decision, concerns about racial profiling were raised by students and parents. Gregory McKelvey, a prominent Portland activist who has been affiliated with Portland’s Resistance and Don’t Shoot PDX, shared his story on Twitter about his experience with a Beaverton School District SRO.

“I had a police officer stationed in my high school. At one point he got a warrant to investigate me for a stolen calculator, that I didn’t steal. He kicked down my door after school one day with 8 other cops in riot gear with guns drawn on my Grandma,” he wrote.

National statistics confirm fears about profiling. According the the U.S. Department of Education office for Civil Rights, black students were 16 percent of the total enrollment for the 2011-12 school year, but 27 percent of the students referred to law enforcement and 31 percent of students involved in a school-related arrest. Additionally, students with disabilities represented about 12 percent of the total student population but accounted for 25 percent of those arrested and referred to law enforcement.

All of this raises some questions. Why is the district spending $1.2 million to have police in schools when they don’t make schools safer? Why did they rush this decision forward, despite urges from students and parents to delay the decision until more listening sessions could be held? The research shows that justice system involvement is extremely detrimental to students when conflict could be resolved other ways. Restorative justice programs and increased funding for counseling would make schools safer places without the constant threat of force.