Part 1: Students raise awareness to stop the pathway to prison

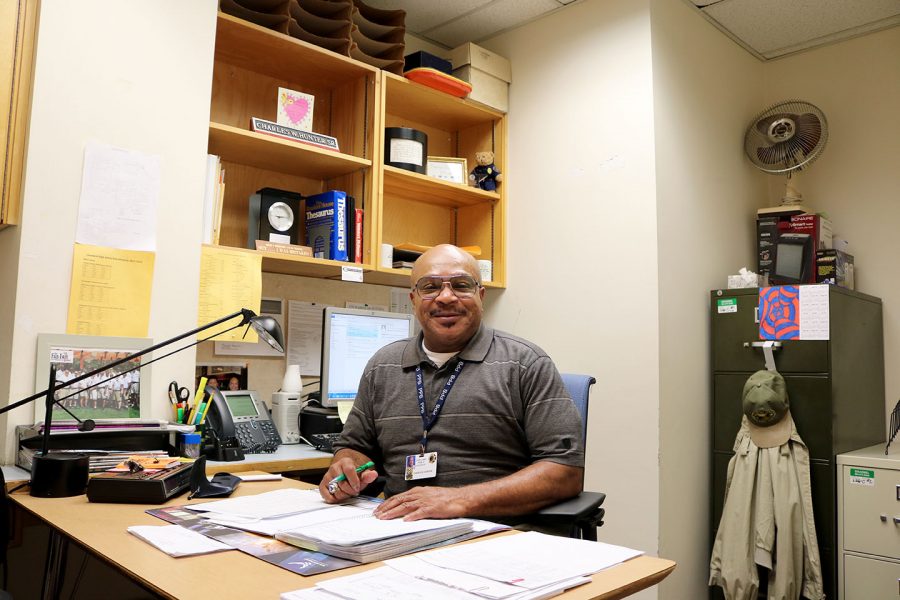

Clarion photo Anna Rollins

Charles Hunter, Restorative Justice Coordinator

April 13, 2016

Many students have different goals after high school. Some desire to continue school in college, others want to go to trade school, a few are planning to go to the military, and still others will start working. No one dreams to go to jail after high school. However, our education system may be setting up students to go down that track.

The school to prison pipeline refers to the “policies and practices that push our nation’s schoolchildren, especially our most at-risk children, out of classrooms and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems,” according to the American Civil Liberties Union. Essentially, the pipeline reflects prioritization of incarceration over education.

Recently, two students opened up a dialogue about this issue at Cleveland. Elise Hodge and Greg Alexander, seniors, presented a 20-minute speech about the school to prison pipeline at a staff meeting.

Hodge and Alexander learned about this topic through Lynne Aller’s Epic Issues class, in which students study issues that are currently affecting the world.

“My mom is an early childhood educator and my sister is in school to be a middle school teacher so education has always been something that my family and I are really passionate about,” said Hodge. “The school to prison pipeline really caught my attention.”

One of the aspects of the Epic Issues course is translating research into action. Hodge immediately had a vision of presenting her findings to the staff in order to create awareness, prompt change, and attempt to interrupt the pipeline at Cleveland.

In their presentation, Hodge and Alexander discussed factors that influence the pipeline. Some elements include inadequate resources in public schools, discrepancy in the classification of “poor behavior,” zero tolerance policies, increased reliance on police, among others.

Oftentimes, there is bias within the pipeline; African American, Latino, disabled, and LGBTQIA are more likely to receive harsher punishments for subsequent offenses compared to other students.

“Students of color are being suspended and expelled at a much higher rate than white students—often for lesser offenses—which leads them into prison,’ Alexander said. “There is a direct correlation between suspension and dropouts. And if you drop-out, get expelled or suspended, you are twice as likely to end up in prison.”

Alexander shared his own experiences about his skin color affecting his education. “When I was in second grade, I climbed two rungs of a ladder and got sent home early. I had an in-school suspension for two days,” he said.

In addition to anecdotal information, Alexander and Hodge included several statistics. They found that the U.S. spends almost $70 billion annually on incarceration, probation, and parole. Between 1987-2007, there was a 127 percent increase in this sector of the national budget, while education received only a 20 percent increase.

Although this is a nationwide problem, Hodge and Alexander didn’t want teachers to distance themselves from the situation.

“I hope that teachers understand that they may not see stuff that is going on in their class and they might not hear everything, but it is definitely there,” said Alexander.

Darryl Miles, vice principal, said, “There are only 4.5 percent of students that identify as African American at Cleveland. There is somewhere between 69 and 72 percent white. But when you go into our data and look at referrals, African American students get twice as many referrals as white students. The numbers tell you that something is screwed.”

Allers stated that many teachers were caught off guard with the idea that this is actually happening at Cleveland. “There is this misnomer that Cleveland is this utopia of schools in PPS. As progressive as we are, we have issues to confront about race and discipline, which I think was jarring for some teachers to hear,” said Allers.

Through the presentation, Hodge and Alexander hope to continue a dialogue about the school to prison pipeline. “We’re not shutting people down or trying to command policies,” Allers said. “Alexander and Hodge simply want to make sure their voices were heard.”

A main aspect of their speech was about the idea of Restorative Justice—a non-punitive approach to discipline. Read the following article to learn about this approach and what Cleveland is doing to try to stop the school to prison pipeline.