Half of History

The popular class Women in History is cut from schedule and Ethnic Studies made an elective as the administration tries to balance course offerings

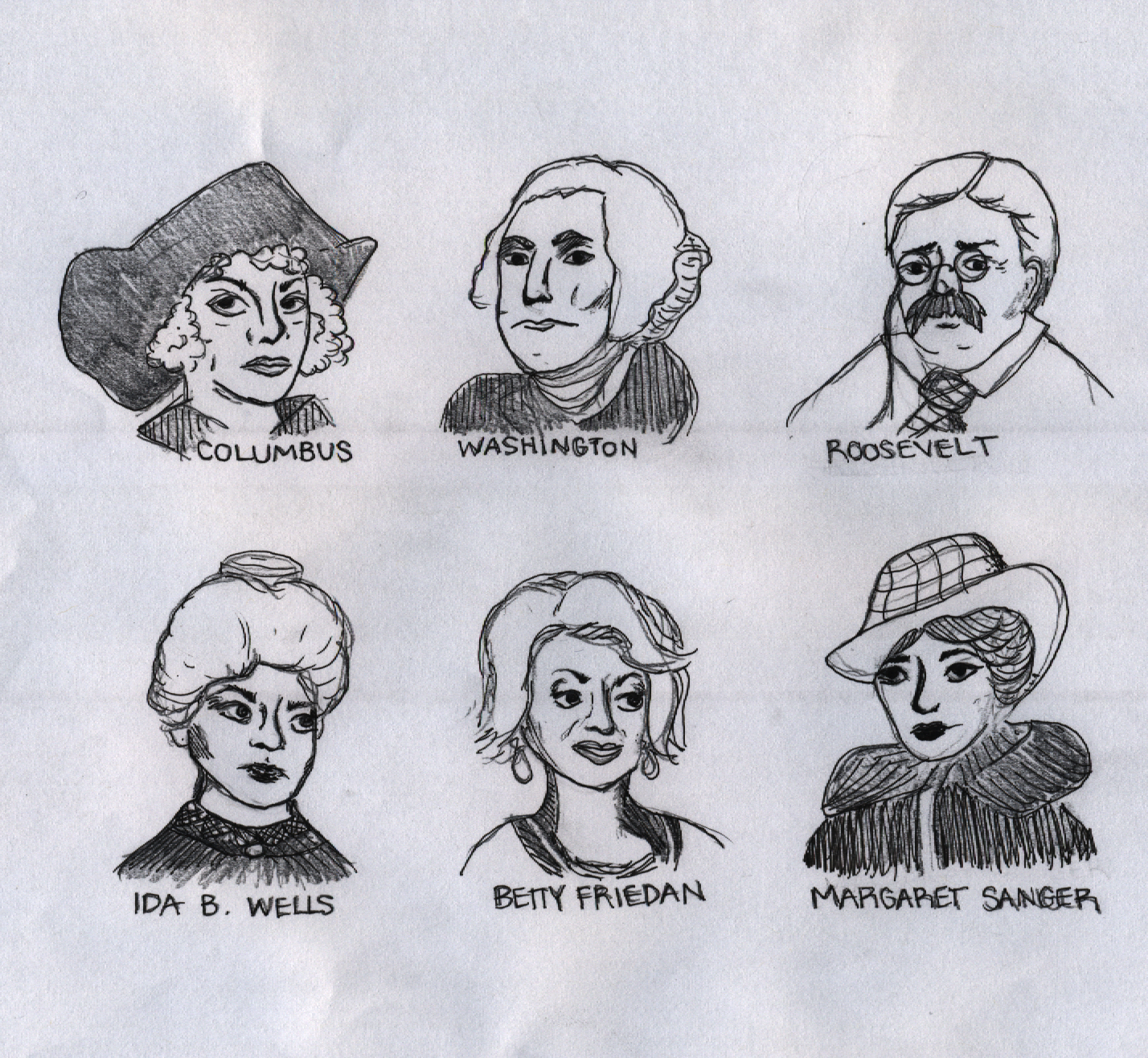

In conventional history classes today, students are often exposed to only half of history. Important historical perspectives from people of color, women, and minorities are omitted regularly, and classes are instead dominated by social studies through the eyes of oppressors. This disparity speaks to the importance of classes that provide the often unheard voices of the past, and their niche within educational communities. It’s safe to say that Cleveland provides some very progressive classes on this subject, including Ethnic Studies and Women in American History, two relatively new classes that currently fill the U.S History credit required to graduate. However, after a long process within the Cleveland administration, the future of both of these courses is up in the air.

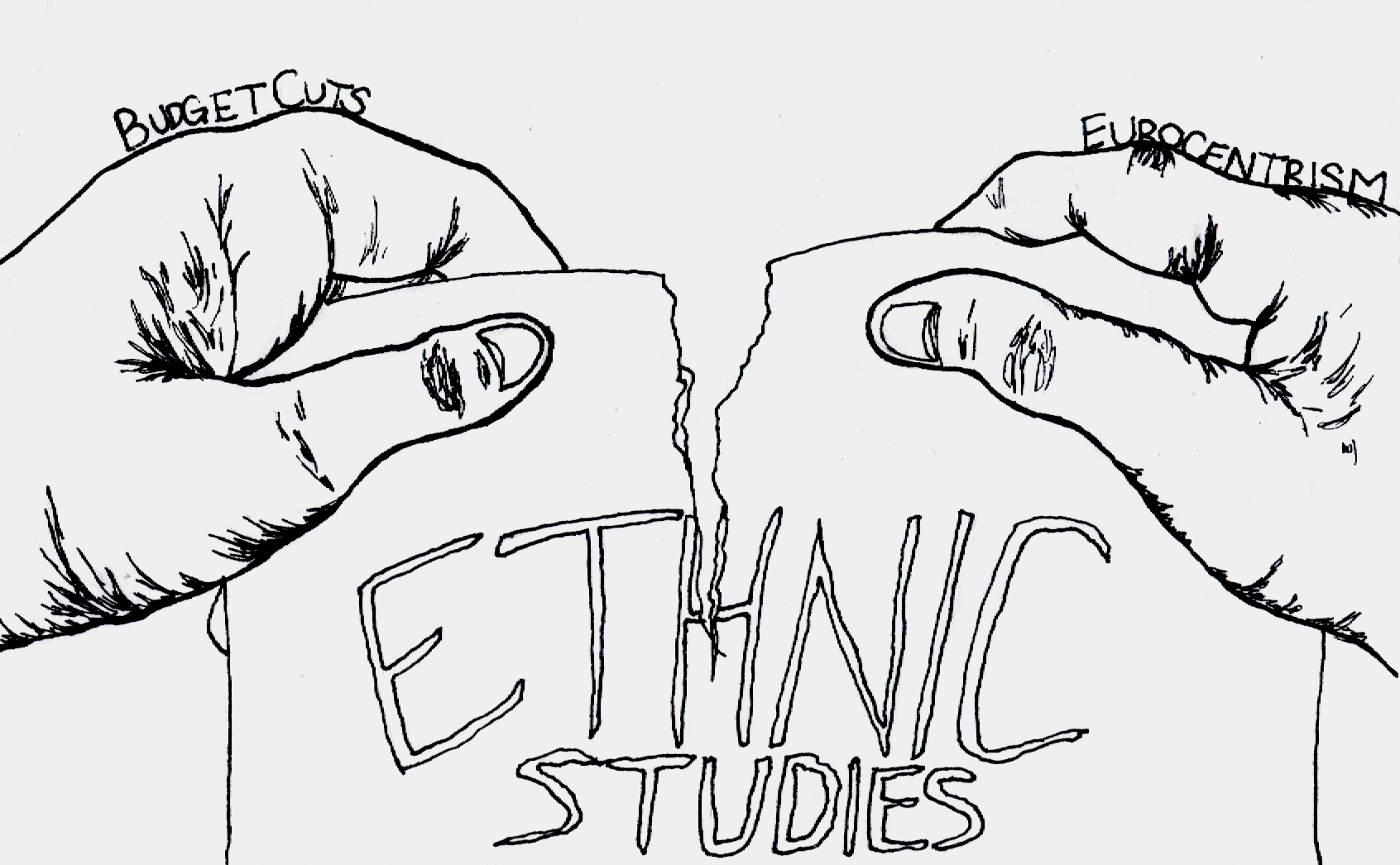

Initially, the prospects didn’t look good. First, IB HOTA (History of the Americas) was newly-established as the only class available to fill the U.S History credit, leaving the fates of both Women in American History and Ethnic Studies uncertain. The verdict from the administration was that Women in American History would be dropped from the course offerings altogether, while Ethnic Studies would be cut from a full-year class to only a semester long elective. These changes were to take effect at the beginning of the 2018–19 school year.

Though it’s too late for Women in American History to be re-implemented, Ethnic Studies was reverted back to a yearlong course as an elective after pushback from teachers, who recognized the class’s importance and unique curriculum. Tim Graham, one of the social studies teachers at Cleveland, was involved in the appeal to the district to make Ethnic Studies a year long class again. “As someone who likes my subject, I’m going to fight for it whenever I can,” said Graham.

Not only was this battle about passion for the subject, it was also about the simple matter of fitting a curriculum designed for a year-long class into a time frame lasting only half of that. After conversation and continued dialogue between teachers like Graham and the administration, the department finally decided in favor of reinstating Ethnic Studies to a yearlong course.

The need for balance

But why did the administration choose to make changes to these classes in the first place? According to Julie

Rierson, Cleveland’s vice principal, the decision was not so much about the altering of Ethnic Studies and Women in American History, but about an increased emphasis on History of the Americas. “The department has been working on this transition for a couple of years, similar to our English department that moved towards every junior taking an IB Language class [IB Language and Literature or IB Literature]. It’s the same thing now in social studies,” said Rierson.

This actually makes a lot of sense — requiring all students to take HOTA may be a step towards closing the perceived gap between IB and non-IB students, a divide that manifests itself in the general notion that the IB curriculum is synonymous with increased rigor and harder classes. This discourages students from taking classes they think they’re not “smart enough” to take, which may create problems with self-esteem.

“I think teachers need to be more inclusive to all learners and not be invested in the hierarchy of IB,” said Anne Dierker, social studies teacher. “We as a community need to stop ‘othering’ students and dividing IB students and non-IB students.” According to Rierson, achieving a comprehensive and well-rounded education is what matters most.

What this explanation doesn’t justify is the decision to completely eliminate Women in American History, instead of switching it to a social studies elective like Ethnic Studies. Apparently, this cut has a lot to do with the school’s objective to balance the electives offered to students, especially art electives. The social studies department already had a handful of electives, including the newly-added Ethnic Studies, Epic Issues, and IB electives like Anthropology and Psychology. According to Rierson, there was no room for the addition of Women in American History to this list. The administration hoped that by cutting Women in American History, students would be more likely to enroll in art electives. In fact, Rierson says the school was looking at potentially losing a few teachers in the art department because they couldn’t fill enough electives in that subject.

“Our job is to look at all the options and determine what we think is going to keep offerings balanced,” said Rierson. “As an IB for all school, one major component of that is the art piece — My hope would be students have a robust, well-rounded curriculum while they’re here. We just wanted to find that balance.”

However, it seems contradictory to eliminate variety in one department for the sake of increasing variety in student’s schedules. Is eliminating popular social studies courses really the best way to achieve this goal? Dierker doesn’t think so, citing the relevance of both classes in schools. At their core, Women in American History and Ethnic Studies are about the accomplishments of the underrepresented people of history, whose stories are only briefly mentioned in textbooks, if at all. These unique perspectives are valuable and worthy of recognition.

“Rather than dwelling on the oppression of marginalized groups,” said Dierker, “we celebrate accomplishments and victories through persistence, through protesting, through uprising, and by simply existing — These two classes are dedicated to investigating and exploring contributions of people who are often ignored and discounted.”

Classes like Ethnic Studies or Women in American History shed light upon these lesser-known accounts, which are a crucial part of obtaining a well-balanced knowledge of history. As a result, students are empowered to take action and make real change. This is a radical and fresh way of presenting history, one that could possibly be lost with the implementation of only one mainstream history class.

This strategy also lacks consideration for students, and what they want to get out of their educations. “It makes no sense,” said Dierker. “If [the administration] wants people to take art classes they should offer more art classes, and students will sign up if they want to. Eliminating choice isn’t a good way to get people to do what you want them to do — We’re not listening to what people want.”

She makes a good point — if art electives don’t have enough students, it’s probably because of a lack of interest on the part of the student body as a whole. It’s obvious that the administration hopes that by avoiding the addition of Women in American History to the electives list, more students will take art electives instead, regardless of where students’ interests lie. Are they justified in this strategy?

There’s reason to think not. Inevitably, there are negative impacts when students are enrolled in classes they have no real desire to take. Dierker says she was faced with a situation like this very recently, after the administration decided to get rid of the U.S History class formerly offered. Juniors who had forecasted for the now nonexistent U.S History course ended up in Dierker’s Ethnic Studies classroom, while many of the students who had signed up for Ethnic Studies were shunned. This resulted in disruption, with students challenging the validity of sensitive topics like cultural appropriation in class.

“I got unwilling students who didn’t want to be there — if you have people who have loud voices and they’re put into a class about women or people of color, then they’re going to make the other people uncomfortable and it’s just not fair,” said Dierker.

This speaks to the repercussions that come with students being in classes for the wrong reasons, in this case creating an environment where controversial issues can’t be discussed in a way that respects all point of views. “It should be a safe place,” said Dierker. “Students already feel unsafe, especially students of color, or women feel unsafe in a class talking about certain things because people are not as accepting.”

An open-minded community is crucial for classes like Ethnic Studies to function well. However, it is made more difficult if students are under the impression that this kind of class is not to be taken seriously.

A Peek into the Past

To gain a new sense of respect for the gravity of classes such as Ethnic Studies and Women in American History, there’s only one place to turn: Their pasts. Both classes have complicated histories, and understanding them will be helpful in comprehending their significance.

Women in American History was created after Dierker says she saw the need for a history class that specifically emphasized women’s roles through history. She got the support of the social studies department and received approval from the site council. From there, it was only a matter of Dierker creating the course description and all of the curriculum for the class, then aligning it to ODE’s standards for U.S history. This is Women in American History’s third year at Cleveland, and is currently taught by Sarah Hardy and Kaley Hambelton. Bella Miller, who’s taking both Women in American History and IB HOTA, says the class is important because “The contributions of women throughout U.S history have been overlooked. I take HOTA as well and I just think there isn’t enough time to learn about all of the perspectives on every issue.”

Even though Dierker played a major part in implementing Women in History at Cleveland, she credits the class’s success to students like Miller. “Without the interest and enthusiasm of students taking the classes, it never would have made it,” said Dierker.

For Ethnic Studies in particular, student involvement played an important role in the creation of the class. The Ethnic Studies Coalition — a group of seven local groups, many of which are student-led — was central in the passing of House Bill 2845, which says that K-12 Ethnic Studies curriculum is required for all Oregon students, with implementation in schools set for 2019. Dierker proposed the class early to the Cleveland administration, who approved it, added it to the course list, and made it available to students for the first time at the beginning of this year. None of this would have been possible without the help of advocates from the Ethnic Studies Coalition, Cleveland students, and politicians.

Over the past year, Cleveland students like sophomores Thida Lam and Anika Becker have taken their involvement to another level. Both Lam and Becker are a part of groups that help come up with what Ethnic Studies should look like across the state.

Lam is a member of the Ethnic Studies Advisory Committee, an organization made up of administrators from across the PPS district, as well as student representatives of minority groups such as LGBTQ, African-Americans, Asians, and Pacific Islanders. They meet every month in Salem, and are currently comparing the PPS social studies standards from 2011 to the Ethnic Studies Standards in 2019. In a PPS Pulse short video, Lam explains what she wants the committee to eventually achieve. “I really hope that this committee accomplishes seeing students who grow up knowing more about their cultural background — most people who are from different cultures just want to know more about their family background, but we don’t get that opportunity here. That’s why I think it’s very important to have ethnic studies in all high schools,” said Lam.

Becker is on the Student Advisory Council, comprised of one facilitator from the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO) and ten student representatives from PPS high schools, including Roosevelt and Jefferson. They meet four times every month, and are trying to construct a clear definition of what Ethnic Studies is for teachers. The council is in constant contact with an advisory of Ethnic Studies teachers, including Dierker, to make sure both parties are on the same page. In a survey conducted by the council last year, students were asked about what qualities they would want in a future Ethnic Studies teacher. “For example, we asked them if they wanted a teacher of color or whether it was important that they had a social justice background,” said Becker.

One of the projects the council is currently working on is designing the way Ethnic Studies will be taught. Instead of textbooks, students will get information through poems, short readings, and documents from primary sources. “We wanted Ethnic Studies to be more student-led,” said Lam. However, all of this decision-making is not solely based on the opinions of the students, teachers, and administrators on the board. “This isn’t a closed sort of thing,” said Becker. “We’re open to taking suggestions.”

The Fragility of Equity

It’s important to consider why the administration chose these two classes in particular to alter. Is it purely by coincidence that Women in American History and Ethnic Studies, the two classes in our school that represent minorities and women, were targeted first? It’s possible that this turn of events speaks to the classes’ inherent vulnerability. “I do think that the fragility of the classes has to do with people in power that don’t think certain things are important,” said Dierker. “You wouldn’t just let anybody teach calculus, you wouldn’t get rid of calculus. We have respect for certain subjects, and then we don’t [have respect] at all for others because they’re not important to some people.”

It all boils down to equity. Catering specifically to women and minorities in classrooms, as Women in American History and Ethnic Studies do, can spark controversy because some claim that this is evidence of unnecessary “special treatment.” This way of thinking might make classes like Ethnic Studies and Women in American History more viable to be threatened, as they have been recently at Cleveland. “There’s a reason why certain things happen,” said Dierker. “There’s a reason why Oregon legislatures have to vote on things like House Bill 2845 — The fact is that we have to have legislation to protect classes that some people think are disposable — Without laws and resolutions, the course wouldn’t survive, because it’s easy to cut things that don’t have a value to them.”

The teaching of only half of history is unacceptable. That’s why having the opportunity to take classes like Ethnic Studies and Women in American History is so valuable. Both classes acknowledge the existence of marginalized groups throughout history and the contributions they made. Ethnic studies is especially unique because it gives students the chance to learn more about the people in the communities around them, and their own heritage. “From my personal experience, Growing up [all I learned about was] colonialism — I kind of regret not asking my parents more about their background, and what they’ve been through, and their journey coming to America — I think future students who learn about these things can help change the world,” said Lam.

In the end, all of the processes involved in the creation and implementation of the classes, all the student involvement and activism, was for the sake of one thing: equity in history classrooms for women and minorities. In reality, the equitable portrayal of history today must include these perspectives, because they’ve been silenced for hundreds of years in favor of eurocentric and patriarchal points of view. That’s the bottom line.

I’m Sophie, and I’m a senior at CHS and a the arts and entertainment editor in chief for the Clarion. This is my third year on the Clarion. My favorite...

Hi, I’m Sam Linder and I write commentary for the Clarion. I’m a senior here at Cleveland and plan on graduating in 2018. Outside of school, I’m...

Malia Walker • Feb 22, 2018 at 7:39 PM

I took Women in history freshman year and it helped me to get my head wrapped around what women were going through early on in history… I hope that they don’t cut that class, because it taught me a lot and I’d like to learn more.

Malia Walker